Carrick Flynn, it seems, has everybody flummoxed.

Rival Democrats running against Flynn in Oregon’s brand new 6th Congressional District struggle to explain how the newcomer candidate went from an unknown to a spending juggernaut, blanketing the district in ads.

Washington, D.C., politicos are bewildered that Flynn attracted unprecedented backing from a political action committee affiliated with powerful Democrats, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. Some have gone as far as to say their party turned its back on minority voters with the move.

Carrick Flynn's campaign for Oregon's 6th Congressional District has attracted national interest. No other congressional candidate in any state this year has attracted even half of the outside spending that Flynn's campaign has.

Courtesy of Carrick Flynn

And pretty much everyone is wondering why a cryptocurrency billionaire, Sam Bankman-Fried, is interested enough in Flynn to spend more than $7 million on his behalf through an affiliated super PAC.

Because of ads and other campaign help funded by that committee, Protect Our Future PAC, Flynn’s campaign is now a national standout. According to data collected by the group Open Secrets, no other congressional candidate in any state this year has attracted even half of the outside spending — money the candidate didn’t raise themselves through their campaign, but that was raised by other groups — than Flynn has.

Bankman-Fried, 30, is no stranger to big political giving. He donated $5.2 million to President Joe Biden’s 2020 campaign, the second-largest amount from any supporter. And as the oft-interviewed mogul recently explained on a podcast appearance, his view is that “the amounts spent in primaries are small. If you have an opinion there, you can have impact.”

Bankman-Fried is from California and currently lives in the Bahamas. Just what has gotten him so interested in Flynn and Oregon has been a matter of endless curiosity — curiosity that he has so far not addressed. Attempts to reach Bankman-Fried through his brother and through FTX, the cryptocurrency exchange he founded, were not successful.

But a look at the two men’s backgrounds suggests a likely nexus for the support: Flynn has spent years working adjacent to, and cultivating contacts among, a niche world that Bankman-Fried has said provided the underpinnings for his desire to make vast amounts of money in the first place.

The quirky young billionaire is one of the most visible proponents of a philosophy called “effective altruism,” which attempts to steer charitable giving toward causes and technologies that will save the most lives and generate the maximum amount of social good.

Effective altruists that “earn to give” like Bankman-Fried are obsessively analytical in their quest to give money in the smartest possible way. And they’re often concerned with two subject areas that Flynn has worked in extensively.

The first is preventing existential threats that could be posed by advanced artificial intelligence. Flynn spent years studying the risks and benefits of artificial intelligence through his work at a U.K.-based organization called The Center for Governance of AI. It’s an affiliate of another group, the Center for Effective Altruism, which serves as a nerve center of the effective altruism movement.

More relevant to the Oregon congressional race, Bankman-Fried and other so-called “longtermists” are also deeply concerned with how to prevent new pandemics. Flynn began studying that issue in 2015 and helped write a policy that landed in a recent White House proposal on the matter.

Flynn says the details of that proposal, if adopted, could lay waste to diseases like COVID-19 well before they can take root. But the plan he helped generate was stripped out of the bipartisan infrastructure bill Congress passed last year and has not found much interest since. That’s a key reason that Flynn says he’s running.

“It’s insanity,” he said. “This is such a core, fundamental thing. ... That’s actually the thing I’d like to work on, is going back and getting that part right.”

—

Flynn’s national support has made him the most visible candidate in the race for Oregon’s 6th U.S. House seat. The brand new district, awarded after the 2020 census, extends from Portland’s southwest suburbs down past Salem and stretches west to the Coast Range.

Throughout the district and beyond, television screens, radio airwaves and mailboxes have been choked with ads paid for by Bankman-Fried’s super PAC. They tout Flynn as a friend to seniors, protector of the vulnerable, and creator of jobs.

In one ad, Tualatin Mayor Frank Bubenik vouches for Flynn’s focus on boosting the district’s economy.

“He’s out there looking out for all of us,” Bubenik says in the ad. The mayor told The Oregonian he had never met Flynn in person but had had “terrific chats” with the candidate.

Voters have also been treated endlessly to Flynn’s life story.

He grew up poor in Vernonia and was homeless for a time after his family home was destroyed in a flood. Flynn had not planned to go to college, he said, but jumped at the chance when he was awarded a scholarship through the Ford Family Foundation. He leveraged a degree at the University of Oregon into acceptance at Yale Law School, and after graduation traveled the world for five years working on legal and human rights issues.

“I think you don’t see a lot of very poor, rural Oregonians anywhere represented,” Flynn said. “It’s such a weird lottery thing that I ended up out of that, so I feel obligated to speak from that perspective.”

Eventually, Flynn landed at the University of Oxford, the epicenter of the effective altruism movement, and later worked as a researcher at Georgetown University. He moved back to Oregon when the pandemic hit in 2020, and currently lives in McMinnville. Willamette Week reported Flynn has been a registered voter in Oregon since he was 18, but voted in just two elections, in 2008 and 2016.

—

Flynn’s campaign is built on more than pandemic preparedness.

On his candidate website, that issue is buried beneath subjects that are potentially more salient to Oregonians: job creation in the tech sector, supporting universal health care, bringing bipartisanship to Congress. Flynn has spoken critically of land use regulations that he believes prevent economic development in the state and talks about how spotted owl protections decimated the economy of his hometown.

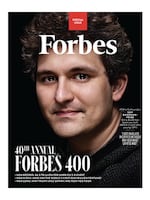

Sam Bankman-Fried, shown on the cover of a 2021 Forbes 400 ranking of the richest Americans.

The Business Wire / AP

But much of the national backing Flynn has received appears rooted in his pandemic work. And through his interest in the issue, Flynn has moved in similar circles to Bankman-Fried within the small world of effective altruism.

Flynn’s wife worked at the U.K.-based Center for Effective Altruism in 2017 and 2018, at the same time that Bankman-Fried did a short stint as the organization’s director of development, according to his LinkedIn profile.

Flynn said recently he didn’t know that his wife’s time at the center overlapped with Bankman-Fried, and said he didn’t think the two had ever spoken. (Bankman-Fried reported working for the organization from the U.S., while Flynn’s wife was based in the U.K.)

“If she’s met him she hasn’t said anything,” he said. “I think she would have said something.”

A more potent connection might be Andrew Snyder-Beattie, Flynn’s boss when both were working at the University of Oxford.

Snyder-Beattie is now an influential and active figure within the world of effective altruism. He awards grants for biosecurity and pandemic preparedness at Open Philanthropy, a group funded in part by Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz that reports rewarding more than $1.6 billion in grants over the last decade.

And Snyder-Beattie has used his influence to boost Flynn among his community. In February, he wrote a post titled “The best $5,800 I’ve ever donated (to pandemic prevention)” in a forum for effective altruists.

The post was effusive, calling Flynn “brilliant and driven” and making the case that donating the maximum allowable amount to his campaign would increase Flynn’s chances of winning — and therefore the chance that he could help steer millions or billions toward pandemic preparedness once in Congress. It didn’t have much to say about Oregon-specific issues.

“You should donate if you think Carrick winning the election would produce more good things in the world than $50 million worth of donations,” Snyder-Beattie concluded after running down a list of probabilities he’d concocted. “Given what I know about Carrick and the fact that Congress spent almost $5 trillion last year, I feel like this should be an easy bar to clear.”

Asked about his support for Flynn in the post, Snyder-Beattie said that, as someone who is constantly thinking about pandemic prevention, he’s enthusiastic about a congressional candidate making it their top issue.

“This is a unique campaign, and my hope is that more campaigns in the future will be fueled by supporters that are excited about how much good a candidate can do in the world, such as preventing pandemics and other important or neglected issues,” he said in an email.

Snyder-Beattie’s online plea perhaps had its intended effect. Flynn’s campaign has reported raising $830,000, more than nearly every candidate in the race. The vast majority of that money has come from out of state, the Statesman-Journal reported.

There’s another visible tie between Flynn and Bankman-Fried — a person with a far-stronger connection to the billionaire than a shared philosophy on giving money. Bankman-Fried’s brother, Gabe Bankman-Fried, is an unabashed fan of Flynn’s work on pandemic preparedness.

“Carrick was one of the few people who cared about pandemics before Covid,” Gabe Bankman-Fried told OPB. “There were not many people thinking about pandemics because we hadn’t had one.”

Gabe Bankman-Fried thinks a lot about this issue. He runs a group called Guarding Against Pandemics that was founded in 2020 and advocates for candidates and policies it says will help the nation and world fortify against future outbreaks. The organization is a dark-money group that can shield its donors but states plainly that Sam Bankman-Fried is a major funder.

Guarding Against Pandemics has endorsed Flynn’s candidacy, and two people who list the organization as their employer are listed among donors to his campaign. One of those donors is Michael Sadowsky, who is also president of the Protect Our Future PAC.

Gabe Bankman-Fried said he believes Flynn could be a leading voice in Congress for pushing new technologies that help quickly corral emerging outbreaks.

“I spend my days as an advocate trying to get members of Congress to think about this,” Gabe Bankman-Fried said. “Everyone is supportive but few people champion it.”

While he said he could not comment on why a super PAC affiliated with his brother had given so much to Flynn, Gabe Bankman-Fried said Sam Bankman-Fried has made no secret about his interests. “My brother and many other philanthropists are very concerned about biosecurity and pandemic preparedness,” he said.

Flynn agrees, though he says that he has never talked to Sam Bankman-Fried or others at the super PAC that has spent massively on his candidacy. Federal candidates are not allowed to coordinate with super PACs, which can raise unlimited amounts of money to spend for or against political candidates and causes.

“I think they just want this bio[security] thing as a win,” he said. “Because I’ve been doing this, I think they think that I’m a very clear person to do it. But, again, I actually am speculating.”

Flynn is not the only candidate Bankman-Fried’s super PAC has assisted this year. The Protect Our Future PAC emerged in January, announcing it would support candidates who took pandemic planning seriously.

The committee has reported spending nearly $2 million supporting U.S. Rep. Lucy McBath, a congresswoman from Georgia who is in a competitive primary contest. It has also helped Texas state Rep. Jasmine Crockett in her congressional bid, spending nearly $1 million. Both women are Democrats and have also been endorsed by Guarding Against Pandemics.

Flynn, though, has seen most of the super PAC’s interest — by a lot. Filings show Support Our Future has spent more than $7 million touting the candidate to Oregon voters. That’s more money than other Democrats in the race have raised (or given to themselves) combined.

—

Flynn’s candidacy has raised hackles in a Democratic primary field that includes eight other entrants. Also vying for the new congressional seat are three women of color with histories in public service — state Reps. Andrea Salinas and Teresa Alonso Leon, and former Multnomah County Commissioner Loretta Smith — along with a physician, an Intel engineer and a cryptocurrency investor.

Those campaigns bristled at Sam Bankman-Fried’s spending on Flynn’s behalf all spring but did so mostly quietly. One candidate, Intel engineer Matt West, filed an election complaint against Flynn in March. As Willamette Week reported, West has alleged that the timing of ads released by the Protect Our Future PAC indicates that Flynn gave the group special access to stock footage from his campaign. Flynn’s campaign has denied the charge.

Flynn’s opponents turned more forcefully against him on April 11, when word emerged that the House Majority PAC, a super PAC closely affiliated with Pelosi and other top Democrats, had sprung for roughly $1 million worth of ads on Flynn’s behalf.

A major force in electing congressional Democrats, the House Majority PAC does not typically weigh in on primaries. Observers say its support of Flynn was unprecedented, and in response, six candidates running in Oregon’s 6th district released a joint statement decrying the move.

“We strongly condemn House Majority PAC’s unprecedented and inappropriate decision…” the statement said. “We call on House Majority PAC to actually stand by our party’s values and let the voters of Oregon decide who their Democratic nominee will be.”

The ad buys also led to charges that top Democrats were abandoning voters of color who helped the party win in 2020. The Congressional Hispanic Caucus’s BOLD PAC, which supports Hispanic Democratic candidates and has backed Salinas in the race, put out an indignant statement.

“Instead of supporting Andrea, House Majority PAC is spending nearly $1 million to prop up her opponent Carrick Flynn,” U.S. Rep. Ruben Gallego, the group’s chairman, said in a statement. “This stands in contrast to the thinking of a majority of Democrats who know that Latino candidates and voters must be taken seriously for the midterm elections.”

Smith, the former Multnomah County commissioner, made a similar charge.”It is frankly shameful that House Democratic leadership in Washington is apparently trading favors and treating one of the fastest-growing regions in the country as a bargaining chip while taking Black voters, and specifically Black women, a core constituency for the party, for granted once again,” Smith, who is Black, said in a statement. “This election will ultimately be decided by the voters of the Sixth District, not the dark money billionaires who refuse to play by the same rules as everyone else.”

Adding his name to the chorus of critics: U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley, wrote on Twitter that it was “flat-out wrong for House Majority PAC to be weighing in when we have multiple strong candidates vying for the nomination.”

For its part, the House Majority PAC has suggested, without offering an explanation, that Flynn is the most viable candidate to win in a general election.

“House Majority PAC is dedicated to doing whatever it takes to secure a Democratic House majority in 2022, and we believe supporting Carrick Flynn is a step towards accomplishing that goal,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “Flynn is a strong, forward-looking son of Oregon who is dedicated to delivering for families in the 6th District.”

Opponents don’t buy it. Speculation has run rampant that the Democratic PAC, which has been outraised by its Republican counterpart this year, agreed to support Flynn in exchange for a piece of Bankman-Fried’s fortune. Democrats are widely expected to face a serious challenge in maintaining control of Congress in the 2022 elections.

“Do I know exactly what was exchanged by his people and [House Majority PAC’s] people?” said Robin Logsdon, West’s campaign manager. “No, but I can speculate, as can everyone, that promises have been made.”

If such a deal has been struck, it has not been revealed yet in federal campaign finance filings. Bankman-Fried, who is relatively open about many aspects of his business, shies away from discussing his political giving in detail. As Politico recently reported, even the millions he donated to the Protect Our Future PAC were obscured in initial funding disclosures.

In his recent podcast appearance, Bankman-Fried acknowledged he sometimes worries about blowback from his political spending.

Then he suggested he’d made peace with it.

“If having positive impact is your goal,” he said, “there’s a limit to how much it makes sense to worry about the PR of having positive impact.”

OPB reporter Sam Stites contributed to this story.