HelenRuth Stephens has asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, seen at her home in 2013. She says hot weather drains her energy and makes it hard to breathe. Stephens lives in a building surrounded by a black asphalt parking lot, a dense network of city streets lined with more apartments and the whirring of traffic on Interstate 405. That means when it gets hot outside, it's even hotter in her neighborhood.

Cassandra Profita / OPB

PORTLAND – On hot summer days, 74-year-old HelenRuth Stephens doesn't dare leave her apartment. Not to get the mail or take out the trash."You don't do it because you'll be breathless by the time you get back," she says.She suffers from asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Both affect her lungs. Hot weather drains her energy, she says, and makes it hard for her to breathe.Stephens is the type of person public health officials worry about as they're preparing for climate change.That's in part because of her existing health problems, but also because she lives in what scientists call an urban heat island. It's a part of the city that soaks up more of the sun's heat because it has a lot of buildings, pavement and vehicle traffic.

Stephens' building is surrounded by a black asphalt parking lot, a dense network of city streets lined with more apartments and the whirring of traffic on Interstate 405. That means when it gets hot outside, it's even hotter in her neighborhood.

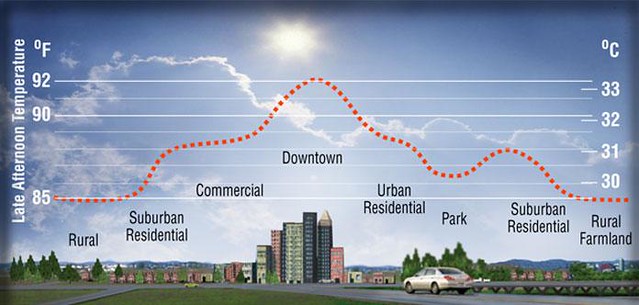

Dark pavement and rooftops heat up the surrounding air.

More than half of the average city landscape is covered in dark, sun-absorbing surfaces such as asphalt or dark roofing, according to Ben Mandel with the Heat Island Group at Lawrence Berkley Labs. Those surfaces can get 60 to 70 degrees hotter than more reflective surfaces or greenery and actually radiate heat into the surrounding air both day and night.

"On a 90-degree day, if a roof has been in the sun all day, it's not going to be 90 degrees. It's going to be maybe 150 degrees as a result of all the heat it's accumulated," says Mandel.

During a heat wave, hot surfaces in the city drive air temperatures in the city even higher.

"The longer the heat wave persists, the hotter the city keeps getting because it keeps absorbing the heat with nowhere to dissipate it," says Mandel. "That's actually the most deadly impact of the heat island effect."

The prospect of hotter summers has health officials taking a close look at urban heat islands. Climate models predict hotter summers and a higher likelihood of extreme heat events in the coming decades, and experts say that poses health risks – even in the milder climates of Oregon and Washington.

"Areas that don't experience extreme heat are the ones that need to be thinking about it the most," says George Luber, associate director of the climate change and health program at the Centers for Disease Control. "While the Pacific Northwest doesn't experience many extreme heat days, the potential of those are greatly increased – more so than other areas of the country."

Jack Sutton cools off near a busy Portland street.

In Portland, studies show some parts of the city can get up to 9 degrees hotter than nearby rural areas. The heat alone poses health risks from dehydration – to the elderly, the homeless, poor people and people with heart disease and diabetes.

But it also creates another problem: It cooks air pollution into ground-level ozone, or smog.

"Ozone doesn't do well with our lungs," says Multnomah County Health Officer Justin Denny. "When the sun mixes with all the soup of pollution in the community from being in an urban environment, what happens is you create this ozone, which is a bi-product. If you have asthma or emphysema, you will find it more difficult to breathe."

Planting trees could help reduce air pollution and heat in cities.

The way Denny sees it, urban heat islands are a double-whammy for people's health. The hottest places in the city are also more polluted. Add climate change to the mix, and the health risks of heart attacks, strokes and asthma attacks are even higher.

"You will take a person who's not that healthy to begin with and push them to where they require medications and hospitalization," he says, "and push people who are healthy into developing conditions like asthma."

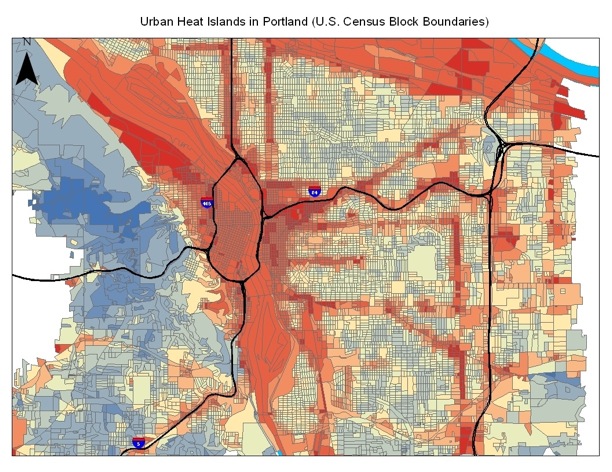

The Multnomah County Health Department is developing a plan for responding to the health risks of climate change. The plan uses census data and maps of Portland's urban heat islands to pinpoint the people whose health is most vulnerable in hot weather so the county can set up cooling centers in those areas during heat waves.

A heat map of Portland shows hotter areas in red – around industrial areas, downtown and along highways – and in and cooler areas in blue.

The maps show a big, blue cool zone in Forest Park – the city's 5,100-acre urban forest – and a big, red hot zone all through downtown Portland.

Portland State University professor David Sailor developed those maps by taking detailed measurements of temperatures across the city during the summer months. He matched the temperatures with the mix of land cover – how many trees and how much green space were in an area compared with the amount of dark, heat-absorbing pavements and rooftops. That gave him a formula he could apply to the whole city to determine whether some neighborhoods run hotter than others.

"There's a fair amount of warming in these dense, concrete, asphalt jungles, freeway interchanges and downtown areas," says Sailor. "And then of course, one thing that's impossible to miss in these figures is the fact that Forest Park stands out as what we call a cool island."

Cities across the country are looking for ways to cool down their urban heat islands – to protect public health and prevent deaths during heat waves.

A 2009 study found climate change will likely lead to more heat and air pollution-related deaths in the Seattle area, where only 8 percent of residents have air conditioning.

With climate change likely bringing warmer summers to the city, urban planners want to know how to make downtown more like an urban forest. Can they reduce the health risks of living in the city simply by planting more trees?

Portland's Multnomah County compared census data with heat islands to create a heat vulnerability index of residents whose health is at risk in hot weather.

Vivek Shandas and Linda George of Portland State University are working on an answer to that question.

They've compiled air pollution data from hundreds of tiny air monitors zip-tied to tree branches, street signs and telephone poles all over the Portland metro area. The monitors measure levels of nitrogen oxide and nitrogen dioxide, two common pollutants in cities that are also ingredients of ozone. Shandas and George are using the results to map how air quality varies in neighborhoods with different arrangements of trees.

Shandas says the research shows that places with more trees are cooler and have cleaner air. So trees seem like a good option for cities dealing with urban heat islands.

"It's relatively easy to put trees in," he says. "It's relatively hard to pull up concrete and roads, and it's relatively hard to change buildings once they're set up."

But even planting trees isn't a simple fix, says George. If you plant trees for shade and cooling in a canyon of downtown buildings, for example, they can actually reduce ventilation and trap air pollution from cars and trucks. She and Shandas are working with PSU tree expert Todd Rosensteil on a way to help cities across the country figure out where to plant trees to create healthier neighborhoods.

"Otherwise, we can look at these maps and everybody can run to where there's clean air, but not everyone can live there," says George. "We need to be able to do something about it."

Thermal photos taken from a helicopter show hot roofs and cool trees in downtown Portland's park blocks, around SW Broadway and Harrison.

So there are still a lot of questions about how many trees to plant and in what formation. Shandas says the new data they're collecting in Portland should offer new insights.

"What we have now are some layers that tell us what's the surface of really bad air and what's the surface of really hot areas," he says. "We haven't quite seen any place in the country or dare I say the world that has actually been able to get at that resolution of information."

One day, Shandas hopes to have a model of what makes urban heat islands hotter and smoggier and what cities can add to cool them off and clean them up.

There’s more to come in our series, “Symptoms Of Climate Change:”

Tuesday: Cities will feel the heat as climate change drives summer temperatures up. It's a phenomenon called the heat island effect.

Wednesday: Scientists say hotter temperatures will bring about more fire seasons that are longer, drier, and likelier to fill the air with smoke that can make breathing more difficult.