I watched a sea lion die last summer. The large animal was emaciated, its spine and ribs visible below its fur. Its hind limbs were immobile as it dragged itself from the shore to the water. Once in the harbor, without the use of its rear flippers, the sea lion struggled to stay afloat. It sank, resurfaced and sank again.

I called a hotline, but it was too late. The animal never came back up.

I later learned that it probably had an advanced form of cancer. This particular cancer starts in the genitals and then attacks the spine before spreading throughout the body. It’s extremely common — in fact, sea lions have one of the highest rates of cancer among all wild animals. Scientists are just beginning to understand the causes.

A California sea lion, named Charlie Winston, stranded on a beach in California. Severe cancer had spread throughout her body and made her too sick to swim.

Marine Mammal Center

For more than 20 years, Dr. Frances Gulland has collected samples of this cancer. Gulland didn’t know if she’d ever learn what caused it, or be able to treat it, but she had foresight. So she gathered the samples and stored them, and hoped that one day there would be a way to study them.

Today, those samples and others provide a gold mine of information and may help us better understand how cancers progress, not just in sea lions, but in humans too.

Gulland's predecessors at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California, first noticed the disease around 30 years ago. The Marine Mammal Center rehabilitates stranded sea lions, otters and seals found along the coast of California, and dissects and studies the animals that wash up dead.

About 20 percent of those dead animals had the cancer, which is perhaps second only to rate of facial cancer among Tasmanian devils.

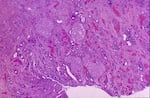

This histopathology of a sea lion kidney shows four large, cancerous masses.

Marine Mammal Center

Scientists knew that for cancer to be as common as it is among sea lions, something had to be causing it. But it wasn’t clear what. So for much of her career, Gulland has spearheaded the effort to pinpoint the cause of the cancer.

Evidence points to three possible culprits: a sexually transmitted herpesvirus, pollutants like PCBs and DDT, and genetics. Today, researchers think some combination of the three is responsible.

All of the animals that develop the cancer have the virus. But that doesn’t mean the virus is the cause, said Dr. Alissa Deming, a veterinarian and researcher at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab. That’s because they also found the virus in seemingly healthy animals. “It’s hard to tease out if the virus is just coincidentally there, because viruses exist. I’m trying to tell, definitively, if it’s causal.”

In humans, there’s another cancer caused by a closely related herpesvirus. In patients with late-stage AIDS, the normally harmless virus causes a serious form of cancer.

Could it be that something was suppressing the immune system of the sea lions, which allowed the herpesvirus to penetrate more deeply into their cells?

Deming and Gulland tested cancerous sea lions for the presence of PCBs and DDT, two pollutants that are known to suppress immune systems. Sure enough, sea lions that had high levels of those pollutants were 6 to 8 times more likely to have the cancer.

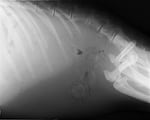

The fuzzy area in this radiograph was thought to be cancer.

Marine Mammal Center

But even that doesn’t confirm the cause. Sea lions that die from the cancer are very thin and emaciated. Since PCBs and DDT build up in fat, the sick animals could appear to have higher exposure to pollutants simply because it’s more concentrated in their bodies.

“You can’t really do experiments on the sea lions. We can’t give them different exposures,” Deming said. “It’s such a dirty, hard thing to work out.”

PCBs and DDTs persist in the environment, especially in the sand just offshore, where they can enter the food chain. There’s no easy way to remove them.

So you can’t stop sea lions from being exposed to pollutants, you can’t stop them transmitting a herpesvirus, and you can’t treat wild animals for cancer. So what’s the point of the research?

“There are two things we get out of it,” Gulland said. “First, we’ve learned that it isn’t something we can do anything about. Imagine if it was a single pollutant accumulating in coastal waters, and we could stop that, and we didn’t know. It’s also another piece of evidence that PCBs and DDTs are harmful. The second is that it can give us insight into cancers in people, like the virally induced cancers in humans.”

Normally human cancers are studied in animals like mice. But sea lions are a lot more like humans.

“We’re both long-lived mammals, we both eat a lot of fish, we’re exposed to the same stressors. We get infected with similar viruses,” Deming said. In short, sea lions are a perfect model organism. And there are a lot of sea lions, so there are a lot of animals to study.

A lot of those severely ill animals end up at the Marine Mammal Center or another rehabilitation site. But since there’s no treatment, eventually the animal dies.

Superstition, a California sea lion, was brought to the Marine Mammal Center. Veterinarians suspected she had cancer, which was confirmed with a radiograph and ultrasound. She died just days after her rescue.

Marine Mammal Center

“As a veterinarian, it was really frustrating to have these animals come in, and they’re in such pain during end-stage disease,” Deming said. “That’s why I decided to go back to school and do my Ph.D. Otherwise, they’re going to be wasted. If we don’t do research on them, they’re just another number.”

These sea lions could help answer one of the biggest questions in cancer biology: Why do some tumors stay in one place and remain benign, while others metastasize and suddenly spread throughout the body? “That is a big black box in science, it’s really hard to study in humans or replicate it in an animal model,” Deming said.

In humans, as in most animals, it isn’t the initial cancer cells that kill you. It’s the cancer that spreads to other parts of the body. According to Deming, only about 10 percent of people will die from the initial tumor.

A unique opportunity to peer into that black box came unexpectedly, when Dr. Julia Burco, a wildlife veterinarian with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, reached out to Deming.

Related: Oregon Starts Killing Sea Lions At Willamette Falls

For a handful of years, ODFW had been removing sea lions that swam up the Columbia River and its tributaries. The animals ate endangered steelhead salmon that congregate at the base of Columbia River dams, waiting to for steelhead to swim up the fish ladder. Steelhead numbers were so low, that ODFW was prepared to try something radical: killing sea lions that returned to the dams multiple times, if they can't first be homed in an aquarium.

Burco saw this as an opportunity, a chance to see just how many seemingly healthy sea lions truly had the cancer. Since the initial lesions appear internally, there’s no way to check for them while the animals are alive.

Burco found that a lot of animals without any visible wounds could have cancer. About 90 percent of the animals she checked carried the virus. In the year that they sampled the most animals, 2017, they found the virus in 37.5 percent of sea lions.

This also gave Deming a chance to study cancerous cells before they became severe and spread. In ongoing research, she and Burco are looking at the genetics of the early and late-stage cancerous cells, to see if certain genes are turned on or off that allow the cancer to spread throughout the body. Then, she plans to look for similar genes in known human viruses and virally caused cancers.

“For me, it lets me sleep better at night, knowing I’m doing something with these animals that are coming in and dying,” Deming said. “I’m paying respect to that animal by learning as much as I can from it. We know we can’t save them all, but we can make them all matter."