Three years ago, the proposed freeway widening project near Portland’s Rose Quarter was a jewel in the crown of a landmark transportation bill passed by Oregon Legislators.

Gov. Kate Brown touted the Oregon Department of Transportation’s claim that the $450 million project would address “one of the worst bottlenecks for freight and passenger vehicles in the entire nation.”

Interstate 5 runs through the Rose Quarter in Portland, Oregon, Thursday, Dec. 7, 2017.

Bradley W. Parks / OPB

Political leaders hoped the I-5 Rose Quarter project – along with similar projects on Interstate 205 in Oregon City and West Linn and Highway 217 in Washington County — would show voters that they were doing something concrete about the rapidly increasing congestion in the Portland area.

Fast forward to 2020, and the Rose Quarter jewel is looking increasingly tarnished. The project’s price tag is threatening to top $1 billion. Climate activists are fighting it. And local officials say ODOT is failing to address the impact of the project on the fabric of the dense urban community around it, including a middle school that backs up to I-5.

Related: Air Quality Report Says Portland Middle School Should 'Limit' Outdoor Activities

Metro Council President Lynn Peterson said ODOT has tried to speed the Rose Quarter project through environmental reviews to avoid getting bogged down.

“But what they don’t consider is the risk of not having community ownership,” she said. “And if you don’t have community ownership, you do end up with the Columbia River Crossing example … and so you have just spent years and time and resources on something that everybody agrees to, and you’d never get to construction.”

The Columbia River Crossing, the multi-billion-dollar project by Oregon and Washington to build a new bridge across the Columbia, was deep-sixed by political opposition in 2013.

Now the Rose Quarter project is at a key turning point. The concerns mounted to the point that the governor ordered the Oregon Transportation Commission to hit the pause button while studying the environmental, social and cost issues that threaten the project.

The commission will meet Thursday, and Chairman Robert Van Brocklin is laying out a long to-do list for the next several months.

“I believe these actions demonstrate our intention to be a constructive partner on the Project,” wrote Van Brocklin, a Portland lawyer.

In short, the heat is on. Here is a look at the major issues facing the project:

The Cost

Back in 2017, ODOT estimated the project would cost $450 million. Now, a new report from ODOT pegs the cost at between $715 million and $795 million – and that doesn't include some key changes to the project sought by local leaders. Add all of that up and it could easily top $1 billion.

When ODOT gave legislators the $450 million cost estimate back in 2017, the agency didn’t bother to forecast the impact of inflation. That accounts for about half of the increase. Metro’s Peterson, who has a graduate degree in engineering, shakes her head at this. Figuring in inflation is something you’d find in a fundamentals of engineering exam, she said.

Related: The Present And Future Of Interstate 5

Lindsay Baker, ODOT’s government relations and external relations director, said it wasn’t clear back in 2017 when construction would begin. She said that made it hard to come up with a solid cost projection.

Still, she acknowledged, “if we were asked do that again today, I think we would probably build in the inflationary cost.”

Construction is now scheduled to begin in 2023. Officials say that they’ve now done enough design and engineering work to give them a lot more information about how much it will cost. That’s also led to major cost increases on everything from land acquisition to lowering sections of the I-5 roadway to accommodate highway covers.

The big issue now is how to pay for all of this. ODOT’s Baker says there are a lot of possibilities, ranging from federal grants to vehicle tolls.

House Speaker Tina Kotek, D-Portland, said she is looking at tolling to avoid cannibalizing other road projects around the state to pay the tab for the Rose Quarter work.

“We now have a challenge before the Legislature of how we do that,” Kotek told reporters Friday during an event previewing the 2020 legislative session. “And one of the things I think we’re going to have bring back to the table is more immediate implementation of region-wide congestion pricing.”

Related: Oregon House Speaker Says Tolls May Be Needed On All Of Portland's Freeways

In particular, she is looking at tolling I-5 and I-205 from the Columbia River through Wilsonville. Oregon has already applied for federal permission to toll smaller sections of I-5 and I-205 around the proposed widening projects on those freeways. But broader tolling could raise a lot more revenue. ODOT has estimated it could generate $300 million a year – and that’s before taking inflation into account.

Of course, tolling faces a lot of opposition. Canby Rep. Christine Drazan, the House Republican leader, said she’d rather that the state shift work to the I-205 widening project next to her district. Right now, that project is waiting in line behind the Rose Quarter.

The Project's Purpose

The guts of the Rose Quarter project is a 1.7-mile section stretching roughly from the junction with Interstate 405 to the Marquam Bridge over the Willamette River.

This cramped bit of freeway includes a series of tricky merges and has more than 200 crashes per year. The vast majority of those are fender benders, but they help produce about 12 hours of daily congestion. The trucking industry’s research arm calls it the 28th worst highway bottleneck in the country.

ODOT plans to install a series of “auxiliary lanes” that it says will reduce the number of crashes and make merging smoother.

Related: ODOT Used Long Dead I-5 Bridge Replacement To Plan Rose Quarter Upgrade

“We fully admit that this isn’t going to eliminate congestion at the Rose Quarter,” said one top ODOT official, Travis Brouwer, after the transportation bill won legislative approval. “But we do expect that it will make traffic a lot better.”

The project includes several other elements besides the auxiliary lanes. They include two covers over the freeway near the Rose Center, a new bicycle and pedestrian bridge and a major reorientation of the entrance and exit ramps at the Rose Quarter.

Those add-ons bought the Rose Quarter project some early buy-in from Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler.

“If somebody came to me and said, ‘Ted, do you want to spend half a billion on a freeway expansion?’, I say, ‘No and hell no,’” Wheeler said at a 2017 City Council hearing. “But that’s not what this is.”

However, local officials have increasingly come to see the non-freeway parts of the project as inadequate. By mid-2019 Wheeler and Peterson were writing a joint letter calling on ODOT to take a much more careful look at several key details involving the project. That includes rectifying the damage that the original construction of I-5 wreaked on North Portland – particularly the largely African-American Lower Albina neighborhood.

“We will only get one shot to help heal the wound Interstate 5 cut in Albina 60 years ago,” Wheeler and Peterson wrote. “We have to get it right.”

Similarly, concerns have grown about the impact of the freeway on Harriet Tubman Middle School. The Portland Public School board has already voted to oppose the highway project if the state fails to do a much more detailed environmental study.

Traffic rumbles by on Interstate 5 near the back of Portland’s Harriet Tubman Middle School.

Jeff Mapes / OPB

Scott Bailey, a Portland Public Schools board member, said he worries that widening the freeway could cause further noise and air pollution impacts on the already overburdened school.

Bailey said the school district has already spent millions of dollars on an expensive air filtration system for the school. And he said ODOT officials “just haven’t done anything close to a thorough assessment” of the added risk of moving traffic even closer to the school.

ODOT officials say they are offering to build a sound wall that would help reduce the impact on the school. But Bailey said the science isn’t there to say that will work.

“If they want to build us a new school – a safe site – go for it,” he added. Ballpark estimate for that: $100 million.

Capping The Freeway

Rukaiyah Adams is one of the most powerful civic figures in Portland. She's chief investment officer at the Meyer Memorial Trust, one of the state's largest charities. She is also chair of the Oregon Investment Council, which oversees one of the nation's largest pension funds. And she heads the Albina Vision Trust, a nonprofit that has developed sweeping plans to recreate a vibrant neighborhood next to the Rose Quarter.

Adams and the Albina Vision board has pushed for a full environmental impact statement on the project, saying that the less-extensive environmental assessment conducted by ODOT is inadequate. In particular, the group wants to beef up the caps so that they could support multi-story buildings and help knit a new Albina neighborhood into the area east of the freeway.

Related: Swingin' Albina: An Oral History Of Portland’s Once Great Jazz Neighborhood

Their call has won wide support in the local power structure, with Kotek, Wheeler and Peterson among those insisting that they want a project that heals the wounds of I-5’s original construction, not exacerbate it.

Adams, an OPB board member, declined an interview. But in advance of Thursday's Oregon Transportation Commission hearing, she let ODOT have it in a series of tweets in which she said the agency "ran that hustle" of offering up wholly inadequate covers over the freeway.

“Those expensive, & wimpy caps, were ill conceived as ‘parks,’” she said. “Who wants to picnic on a piece of patch above a freeway[?]”

ODOT has so far offered only the roughest estimate — $200 million to $500 million — of the cost of more robust caps. Adams said the agency has dragged its feet on seriously looking at how to build better freeway covers.

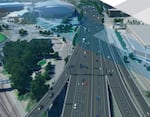

This ODOT image shows its plan for highway covers over a section of Interstate 5 near Portland's Rose Quarter.

Courtesy of the Oregon Department of Transportation

Van Brocklin, the transportation commission chair, said he will propose Thursday that ODOT produce a final report by October explaining how to develop caps and other elements that “promotes the redevelopment of the Albina neighborhood.”

If this substantially increases the project’s cost, that could meet some pushback from legislators outside Portland who are primarily concerned with widening the freeway.

“If Portland wants to put lids and all that kind of stuff on freeways, the state’s job is to make sure whatever we do allows that to happen, but we’re not paying for it,” said Sen. Lee Beyer, D-Springfield, chairman of the Joint Transportation Committee. “That’s a local decision, local desire … It’s not part of the state highway system.”

Environment

The growing movement to fight climate change has fueled the fight against putting any money into widening the freeway.

“If we aren't preparing for the radical changes that are coming ahead and we don't have the leadership that has the guts, they need to step aside,” said Aaron Brown, the leader of No More Freeway Expansions. “Climate leaders don't widen freeways.”

Related: Opponents Dominate Hearing On Portland Rose Quarter I-5 Expansion Project

Brown and Joe Cortright, a Portland economist who has also been an influential opponent, argue that any reduction in congestion will only be temporary. They say widening I-5 will spur more demand, quickly filling up the freeway again. That means more idling vehicles producing more pollution affecting the surrounding community.

ODOT officials and other supporters of the expansion argue that improving traffic flow among all the interchanges in the Rose Quarter area won’t necessarily increase demand. And they point out that ODOT is also studying tolling to see how that helps manage demand.

Cortright has long argued that ODOT should toll at least that section of I-5 before going ahead with the project.

“You’re much better to put the congestion pricing in first and see what capacity if any you need,” he said last year. “Then you can spend that money much more wisely.”

Van Brocklin said the commission will consider “further steps” to integrate tolling with the freeway project. But even many of the local officials who have been slamming ODOT don’t oppose the project.

Peterson, for example, called it an “important congestion-relief project” that could increase safety. She said her focus is on making sure the agency studies all the issues involved in getting the project right.

“We need to have a conversation about the complete package,” she said, “and you put that into perspective when you do an environmental impact statement.”

The Rose Quarter project overview shows an ODOT rendering of what its freeway widening project would look like near the Moda Center and the Oregon Convention Center.

Courtesy of the Oregon Department of Transportation

ODOT has so far resisted calls for a full environmental impact statement that would call for the agency to consider a wide range of alternatives. Instead, Peterson said the environmental assessment isn’t as rigorous.

Van Brocklin said he wants to decide by March 20 whether to conduct a full environmental impact statement. In addition, he’s interested in further study of air and noise quality issues – and of the project’s impact on Tubman Middle School.

Sen. Brian Boquist, R-Dallas, headed a committee that put together the list of Portland highway projects included in the 2017 transportation bill. He said the Rose Quarter project was always going to be difficult given I-5’s location in the middle of a dense urban area.

“You still have to transport these products and we have this chokepoint,” he said. “It’s just the bottom line. And we’re really out here, unfortunately, trying to pick the best of maybe what people would consider the worst solutions.”