Archaeologists work to excavate ancient human artifacts at Cooper's Ferry in Western Idaho.

Loren Davis/Oregon State University

Ancient human artifacts found in a remote corner of Northwestern Idaho could deliver a major blow to a long-held theory that North America’s first humans arrived by crossing a land bridge connected to Asia before moving south through the center of the continent.

The artifacts have been dated to as far back as 16,500 years ago, making them the oldest radiocarbon dated evidence of humans in North America, according to research published Thursday in the journal Science.

The artifacts are part of a trove discovered where Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, now stands. They are a thousand years older than what has previously been considered North America’s most ancient known human remains. Together with dozens of other archaeological sites stretched across the continent, it helps decipher the story of when, and how, humans first arrived.

"The traditional model is that people came into the New World from northeast Asia and walked across the Bering land bridge, before coming down the middle of the continent in an ice-free corridor," said Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University and the lead author on the study. Those people supposedly brought the technology to make Clovis-type blades and spear points with them, and then spread their shared culture across the continent. That's the model currently taught in most history books.

The site at Cooper’s Ferry doesn’t fit with this model. For one, the ice-free corridor probably didn’t exist when humans first arrived at Cooper’s Ferry — scientists think it didn’t open up until about 15,000 years ago, which means these early people had to find a different route south. Other early sites challenged this theory, but none were this old, and the oldest were dated with a method considered less precise than radiocarbon dating.

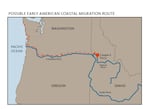

Ancient humans may have moved by boat down the coast, and turned left up the Columbia, following the river to its tributaries and their eventual home at Cooper's Ferry.

Teresa Hall/Oregon State University

“This is another domino in the collapse of the Clovis-first idea and the idea that people walked down an ice-free corridor some 13,500 years ago,” says Todd Braje, an archaeologist at San Diego State University, who was not involved in the study.

“What’s really interesting about Cooper’s Ferry is that it takes things a little further,” Braje says, “It offers some potential avenues for figuring out these big questions.”

Braje supports an alternative theory to the ice-free corridor: one where instead of traveling to the New World by land, ancient Americans came by sea. They traveled from Asia to North America by island-hopping and hugged the shore, following a coastal "kelp highway" full of sheltered bays and rich with food. The idea was once controversial, but in recent years it's gained support.

Just like the ice-free corridor model is supported by a shared technology and shared culture found across a region, the kelp highway hypothesis also has a uniting technology: stemmed points. These are blades, spear points, knives, and cutting tools all manufactured the same way, and are one of the oldest types of projectiles in the world. While stemmed points are plentiful along the coast of Asia, there were very few found at the older sites in North America, and crucially, even fewer found along the coast.

Of course, if Braje’s kelp highway theory was true, there would be very few archaeological sites along the West Coast of North America: sea levels have risen dramatically since the Ice Age, so any human settlements would have flooded long ago.

Related: Luther Cressman, Quest For First People

That’s where Cooper’s Ferry comes in.

OSU’s Davis first began excavating the site in the 1990s. His team uncovered stemmed points and dated them to over 13,000 years ago. At the time, there were no other examples of that technology from that time in history in North America, “we sort of sat in limbo for a time as people argued about what it might mean,” Davis said.

They resumed excavation in 2009. And in 2017, Davis and his team once again started finding stemmed points. “The radiocarbon dates we were getting started to tell the same story. And then, it started to show they were even older than we realized. That was super surprising.”

The stemmed points were extremely similar to a type found in Hokkaido, Japan, also dated to around 16,000 years old.

Combined, Davis said this supports the hypothesis that the first Americans didn’t arrive by land, but by boats.

Braje agreed, “When you look at the illustration Davis had in there, of stemmed points from Japan, and the kind he was finding at Cooper’s Ferry, it’s really striking and very exciting.” Though it isn’t definitive, he says, it offers new avenues of study.

Although the site at Cooper’s Ferry is inland and far from the coast, it sits at the conjunction of two major rivers that serve as tributaries to the Columbia. “If you’re traveling south along the West Coast, the Columbia River is pretty much the first left you can take,” Davis said.

Cooper's Ferry sits on the Salmon River in Idaho, near where it meets the Snake River. People occupied the area for thousands of years.

Loren Davis/Oregon State University

It would be easy enough to then follow the river, rich with fish, to the confluence of two of its tributaries, the Snake and Salmon Rivers, and the spot along their banks where Cooper’s Ferry now stands.

And the ancient people who first settled at this location apparently liked it there: the archaeological site, which contains fire pits full of mammal bones (including enamel from the tooth of an extinct horse) and numerous tools — signs that it was visited by humans for thousands of years. Indeed, the region was known to the Nez Perce Tribe as the site of an ancient village named Nip.

If humans did arrive in Idaho by following the Columbia, there may be more archaeological sites along the river and its tributaries. There’s just one problem: about 15,000 years ago, the massive, landscape-shaping Missoula Floods swept down the Columbia. They just missed the location where Cooper’s Ferry stands by a few kilometers. Anything downstream at a lower elevation would have been obliterated.

Davis thinks archaeologists could find more sites by looking at higher-elevation Columbia tributaries, but he has no plans to search for them yet. He’s got ten years’ worth of artifacts from Cooper’s Ferry to go through.