OPB reporters Cassandra Profita and Jes Burns with plastic found on an Oregon beach. Some plastic that ends up here likely entered the ocean via river.

Todd Sonflieth / OPB

OPB is examining the ways plastic is altering our relationship with the environment and what we can do about it.

We decided to do 15-minute samples because it’s what some scientists had done in Europe. We didn’t think about the consequences.

Like, what it might feel like to be the one sitting on a submerged rock shelf in the Rogue River, just barely winning a stand-off with the current that wants to yank the plankton net out of your hands.

And you’ve been there for seven cold, wet minutes, and you’ve still got eight cold, wet minutes to go. Then you’ll have to do it two more times in this same spot before you can move to another location.

But we settled on 15-minutes samples because rivers are big and what we were looking for is tiny.

Filtering the river water with an ultra-fine meshed net is one of the few ways available to determine if, and to what extent Oregon’s rivers are polluted with plastic – specifically microplastic, which by definition are less than 5 millimeters long — about the width of your pinky nail.

Some of the plastics littering Oregon’s rivers are easy to see. But scientists are also finding microscopic plastic pollution in rivers across the globe.

When my OPB colleague Cassandra Profita and I started asking questions about microplastic pollution in Oregon’s rivers in the summer of 2018, we couldn’t find any answers.

“Most of the microplastics sampling work has all been done in the oceans,” said Eric Dexter, a doctoral candidate at Washington State University Vancouver. “More recently researchers are starting to turn their attention toward lakes and rivers.”

That trend hadn’t reached Oregon. Nobody had looked, or at least no one had published any data at the time.

So we decided to embark on our own scientific journey to test for microplastics in some of Oregon’s most iconic rivers: the Columbia, Willamette, Deschutes and Rogue.

Even though we strongly suspected we’d find microplastics in our rivers, our results were something of a clean sweep: we found microplastics at every site – even in the most pristine, unpopulated area high up in the Rogue River watershed.

But hotspots did emerge. At the top of the list for both concentration of microplastics and pieces passing per hour: the Willamette River in Portland.

Based on our findings, we estimate that more than 57 million microplastics passed through the city on the day we took the samples, making their way toward the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean.

The Problem

Plastic is a tricky thing. For all intents and purposes, once it’s manufactured, it doesn’t go away. It just breaks down into smaller and smaller particles. Once it breaks down, it becomes much more difficult to remove from the environment.

An increasing amount of plastic is ending up in our oceans. It’s floating in great patches in the middle of the Pacific, it’s washing up on our beaches, and it’s inside the shellfish that we eat.

Related: Plastic's New Threat: Indestructible Rafts For Ocean-Crossing Invasive Species

A 2016 report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the World Economic Forum predicts the ocean will contain more plastic by weight than fish by 2050.

Portland State University scientist Elise Granek studies plastic pollution in oysters and clams. Her lab is helping us with the project.

“We are finding microplastics in multiple different kinds of marine organisms that live along the shore, so in the estuaries,” she said. “It’s possible that ... some of those microplastics are coming from rivers that enter the estuaries.”

The study of these kinds of plastics in the environment is relatively new, scientifically speaking. We’re beginning to get a sense overall of how extensive the pollution is, but there’s still much to learn about the potential consequences.

“We do know that there’s a number of chemical compounds that are used in the manufacture of plastics, that then are in those pieces of plastic that get ingested by animals,” Granek said.

Granek’s lab at PSU has found microplastics in oysters grown in Oregon. Other studies have shown that certain kinds of microplastics can impair reproduction in Pacific oysters and can induce neurotoxicity and DNA damage in a type of clam common in Europe.

What that means for humans who eat these creatures or ingest or breathe in microplastics from other sources is still unknown. One recent analysis estimated the average American ingests 74,000 to 121,000 pieces of microplastic per year.

The Plan

We tested a total of eight sites along Oregon’s most populated rivers: two spots on the Deschutes, two on the Rogue, three in the Willamette River watershed and one on the Columbia, just downriver of Portland and Vancouver, Washington.

Locations where OPB sampled rivers for microplastics.

Tony Schick / OPB

The sample locations were chosen intentionally to cover the rivers both above and below the major population centers to see if and how much of a difference cities and towns make.

Plastics are getting into the water in a few ways. First is litter, plain and simple. Escaped plastics from the fishing and oyster industry are relatively common, as is plastic waste from industrial uses, like the raw plastic pellets used in larger-scale plastic manufacturing and molding.

Another way is septic systems and wastewater treatment plants.

“We’re pumping everything that comes in. Wastewater, organic matter, inorganic matter, trash, plastic. It’s everything that goes down the drain whether it should or not,” said Chris Maher, an operations analyst at the Rock Creek Wastewater treatment plant in Hillsboro.

This includes fibers from synthetic clothing – like fleece, nylon and polyester – that break off in the washing machine. The plant uses sand filters to remove fine particles, which he says takes out 90%-to-99% of the plastic.

“If you’re talking about fibers, that stuff will pass through a filter like that,” he said.

When these “pass through” at Rock Creek, they flow into the Tualatin River, which connects to the Willamette, which connects to the Columbia, which then flows to the ocean.

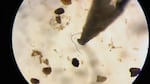

Microplastic fibers are less than 5mm and often show up a vivid color under the microscope.

Todd Sonflieth / OPB

Membrane filtration technology is available that would filter out more of the plastic (and essentially ensure water meets drinking-quality standards), but there’s a balancing act facilities like Rock Creek are considering.

“Obviously that’s a cost,” Maher said, referring to the infrastructure and energy expenditures that would be needed to install a system like that.

He adds to this the unknowns associated with microplastics.

“We don’t know the human health effect of ingesting this plastic. We don’t know [if] the plastic acts as a transport vehicle for other pollutants, other pathogens or anything like that. Research is very new on it, so hence the reason we’re not actively designing for plastic removal,” he said.

Because of the limited number of river samples we’re able to take for this project, we’re remaining cautious about what conclusions can be drawn from our results.

Our sampling won’t tell us where plastics are coming from, but we do hope it reveals if there’s plastic present in the water and how much is passing downstream.

The Results

"We’re looking for something that looks like it shouldn’t be there. Like bright colors or really white or really standard shape,” Dorothy Horn said, explaining what microplastics would look like under the microscope.

Horn is a Ph.D. candidate at Portland State University. She works in the lab that’s processing the samples and verifying if what we visually identify as plastic actually is. PSU undergraduates Ashley Peterson and Amy Valine were invaluable to our project as well.

Related: Plastic Pollution Is Everywhere. What Can We Do About It?

Even though Peterson chemically dissolved the living material in all the samples, the petri dishes are still thick with organic-looking sludge.

“It’s like hunting through the forest,” Horn says as she starts poking through the dish under the microscope with a needle-like probe.

Despite this, it only takes a few brief seconds for the first piece of plastic to appear.

“That is white and that totally to me looks like a piece of plastic bag,” she says.

The discovery is both exciting and horrifying – thrilling to see the fruits of hours of sampling and then stomach-knotting to realize that our rivers aren’t immune to this nearly-invisible pollution.

In all we found two kinds of microplastics in our samples: fibers and particles. Fibers come off things like clothing, fishing nets and ropes. The particles come from other kinds of plastic breaking down into smaller and smaller pieces. There were considerably more plastic fibers than particles present in our samples.

That’s not the only thing to glean from our citizen/journalist science project.

“Our amount of microplastic is increasing as we move downstream,” said Granek, the scientist who helped us make sense of our results. “We do see that — a fairly strong correlation between population in the vicinity and microplastic numbers.”

We found the most plastic by far in the samples from the Willamette River in Portland, in a spot where close to a million people live within 10 miles of its banks.

To get a rough idea of how much microplastic is flowing through the city, we multiplied our results by the total volume of water in the river. We estimate there were more than 600 microplastics floating down the Willamette every second on the day we collected our water samples.

"That’s pretty astonishing when you look at that," said Travis Williams with the environmental group Willamette Riverkeeper. “Just the per second number is pretty crazy.”

Relative microplastic concentration is based on river samples collected in September 2018. Findings were extrapolated using the mean average water flow as measured at the nearest USGS or Oregon Water Resources Department flow meter.

Jes Burns / OPB

More than 600 particles per second adds up to more than 57 million nearly invisible bits of plastic floating through the city over the course of the day.

OPB's Cassandra Profita and Jes Burns look for microplastics at a Portland State University lab.

Todd Sonflieth / OPB

On the Columbia River at St. Helens, the microfiber flow was more than 50 million. More than 2 million microfibers passed that day in the Willamette River at Albany.

Even high up in the Rogue River watershed, in a spot where nobody lives for miles, our results suggested more than 22,000 microplastic particles flowed by on the day we tested.

Williams says microplastic could easily be hurting wildlife – like the freshwater mussels, a species his group has worked hard to protect. The mussels spend their entire lives filtering food from the bottom of the river.

“There’s some potential that there’s plastic in the food web in the river, whether that is small organisms or fish that people fish out of the river or salmon coming upstream,” Granek said.

Scientists are finding these microplastics everywhere – including some rivers at much higher levels than we found in Oregon. Granek says they’re in our air and our drinking water - and that’s not all.

“They're in beer. They're in fish. They're in shellfish. So, unfortunately, it's perhaps not surprising to find them in our rivers, even in areas that we would consider more pristine.”

Next in our series on plastic in the environment: What can we do about plastic pollution?