Plastics are everywhere — including the stomachs of oysters and razor clams up and down the Oregon Coast.

Several studies have shown that microplastics, which are tiny pieces of plastic that make up other larger plastic items, can make their way into fish, crustaceans, clams, oysters and ultimately into us, the people that eat them.

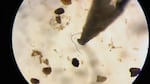

Microplastic fibers are less than 5mm and often show up a vivid color under the microscope.

Todd Sonflieth / OPB

The latest of these studies was published Tuesday in the journal Limnology and Oceanography Letters. It’s the first such scientific paper to look at microplastics in razor clams.

Related: Plastic Pollution Is Everywhere. What Can We Do About It?

Britta Baechler, a doctoral candidate at Portland State University and the lead author on the study, wanted to know if where the shellfish lived and the time of year they were harvested had any impact on how much plastic would be in the animal.

Baechler and her colleagues sampled shellfish from 15 locations on the Oregon Coast. All told, they looked at 141 Pacific oysters and 142 Pacific razor clams. Samples were taken in both spring and summer.

But the mollusks couldn’t escape the abundant plastic particles: only two organisms out of the almost 300 found were free of plastics.

The oysters, which are farmed in estuaries at the mouths of rivers and might have more exposure to pollutants than the beach-dwelling razor clams, had the most plastic. But Baechler said it’s not clear if that’s because of where the animals were living, or if it has something do with differences in how the animals eat and process food.

Baechler also found that the animals collected in the spring were more likely to have plastic in their guts than the animals collected in the summer. It’s possible that’s because plastic-based, moisture-wicking, cold-weather clothes made from fleece are more likely to be washed in the winter.

“Laundry can have a really high concentration of microfiber waste,” Baechler said. And from the laundry, it’s a quick trip to the sea.

Related: Hunt For Answers Shows Oregon Rivers Not Immune To Microplastic Pollution

“But sort of going back and puzzling out why that may be, we started looking through precipitation data for spring and summer,” Baechler said. She found that it was an unusually rainy spring during the sample year and an unusually dry summer. Since plastics travel by river from our cities to the ocean, increased runoff from rain could put more plastic in the water.

Another question Baechler and her colleagues would like to answer: Is the plastic in those animals making it into us?

That’s also unclear.

“We weren’t able to study that, but there have been some really neat studies in labs that look at how good bivalves are at eliminating plastic,” Baechler said.

Some of those studies suggest that bivalves (animals like oysters and clams) might be very good at spitting (well, sort of "pre-pooping") out tiny plastic bits as mucus-wrapped “pseudofeces” before the contaminants even make it into the animals’ gut. It’s how clams avoid accidentally eating tons of dirt.

Other studies have shown that even once the plastic is in the digestive tract, shellfish, which are the garbage-eaters of the sea, can quickly eliminate the plastic in actual feces, “within a number of hours,” said Baechler. But so far, those studies haven’t looked at oysters or razor clams specifically.

Baechler said this is study shows how actions taken on land -- sometimes very far inland -- can eventually make their way into the ocean.

Earlier this year, an Oregon Public Broadcasting investigation, conducted with Elise Granek, a marine scientist at Portland State University and the principal investigator on Baechler's paper, found microplastic in rivers and streams all around Oregon. Even remote and seemingly-pristine streams weren't found to be microplastic-free.

And if it’s in the water (and the air and our food) then it’s probably inside of us, too.