Tobias Read has reason to feel good about his reelection chances this year.

Read, the Democratic Oregon state treasurer, faces opposition from a Republican whom he beat narrowly in 2016, in a Democrat-dominated state where voters will be primed to vote against President Donald Trump.

And then there are the checks.

To get out his campaign pitch, Read will have help in the form of tens of thousands of dollars from out-of-state law firms. As of early December, more than 40% of the money the treasurer reported raising in 2019 came from big-time firms headquartered in places like New York City, Washington, D.C., and Wilmington, Delaware.

That in itself is notable, but the donations come with a further wrinkle: Nearly all are being made by lawyers who seek work from the state of Oregon — work that Read’s office can help provide. A 12-year-old state law gave firms a chance to make millions of dollars if they are picked to work one of the potentially lucrative lawsuits that Oregon files against powerful corporations.

The result is a torrent of outside money to state candidates, much of it solicited by Oregon treasurers and attorneys general — the same elected officials whose offices decide which firms get the work.

Tobias Read is Oregon's state treasurer. He is running for reelection with help of big money from out-of-state law firms.

Campaign Photo

Read’s just one recipient of the largesse, albeit a dramatic one. Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum and an array of past treasurers and attorneys general have been helped by the same lawyers.

Legal experts and campaign finance watchdogs say this is a system that smacks of self-dealing, giving influential politicians a stable of moneyed and motivated campaign supporters while law firms get a shot at making millions.

"It has a terrible odor, doesn't it?" said James Cox, a professor at Duke University School of Law who has studied the issue extensively and helped bring changes in North Carolina. "Whether this corrupts their decision or not, they ought to be sensitive to the fact that it stinks."

Outside Help

Since 2008, class action law firms around the country have poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into Oregon politics. The vast majority of that money has gone to races for state treasurer and attorney general, the two officials who have a say in which law firms qualify for lucrative work.

Source: OreStar

Recipients of the money say donations haven’t influenced the state’s choices, but evidence suggests generosity has its perks.

While dozens of firms have vied for the chance to represent Oregon, only a few have historically gotten the business. Those firms have given substantial amounts to sitting state treasurers and/or attorneys general — a practice that wouldn't be allowed in a growing segment of states. They have also reaped or shared more than $250 million from legal settlements won on behalf of Oregon retirees and others.

The system could amount to more than just bad optics: One study suggests that states allowing such large donations tended to support higher attorney fees, effectively ceding money from legal settlements that should flow back to the state.

In at least one case involving Oregon, attorneys with a favored firm were awarded more than $1,000 an hour.

"It has a terrible odor, doesn't it? Whether this corrupts their decision or not, they ought to be sensitive to the fact that it stinks."

James Cox

Duke University professor

Read insists there’s nothing untoward about the donations he’s received. Both he and Rosenblum say they remove themselves from decisions about which lawyers win state work, even as they ask law firms for reelection money.

“I assume it's because they like the agenda I have and they'd like to see me succeed,” Read said when asked why out-of-state firms support his campaign. “I have that same reaction anytime we're lucky enough to have a contribution from someone. Beyond that, you’d have to ask them.”

The firms, for their part, largely refuse to discuss their donations. One Florida attorney who did grant an interview said her interest is in supporting candidates that align with her values.

Meanwhile, the contributions keep rolling in.

OPENING THE FLOOD GATES

National class-action firms haven’t always taken such a keen interest in Oregon politics.

Oregon law used to prohibit the state pension fund — which wields $75 billion that it invests for retirees — from suing on behalf of itself and others.

That changed during the 2007 legislative session, when then-Treasurer Randall Edwards pushed a bill to allow Oregon to serve as a lead plaintiff in class-action lawsuits, effectively taking a more aggressive role against companies that defraud investors.

“From my perspective, this was another way to protect investments and to protect investors,” Edwards said recently.

By serving as lead plaintiff, officials at the Oregon State Treasury and Department of Justice argued they could win back millions lost when a company’s stocks tanked because of its own misdeeds. Oregon could use its heft to force companies to implement lasting fixes, they said.

The bill passed with little discussion from lawmakers, and launched Oregon into a new, highly complex legal arena.

Securities class-action suits — the technical term for the cases — can generate huge paydays for firms who take them on, even as they win back a small portion of investors’ total losses. But the suits come with risks. Attorneys often receive no money unless the outcome is favorable to the investors they represent.

Further complicating matters, lawyers attracted to such a risk-reward system often have a small pool of clients for which to compete. Congress in 1995 passed a law giving the largest investors — entities like state pension funds — preference for serving as the lead plaintiffs in these kinds of lawsuits.

In the years after that act passed, big checks started flowing to pension officials in states like New York, Louisiana and Ohio, spurring concerns about impropriety. In 2009, for instance, the treasurer of Rhode Island returned thousands of dollars in contributions from firms angling to represent that state in class-action suits, acknowledging the money might create a perception of a conflict of interest that he wanted to avoid.

When Edwards’ bill took effect in early 2008, Oregon became the next target.

Even before Oregon filed its first class-action suit in April 2009, class-action firms had pumped tens of thousands of dollars into the campaign accounts of then-Treasurer Ben Westlund and Attorney General John Kroger.

They never stopped.

In the last 11 years, firms or their lawyers have given at least $690,000 in Oregon. About 93% of that money has gone to incumbent attorneys general or state treasurers, or to leading candidates for those posts when no incumbent exists.

The interest in those two positions is not a coincidence.

The Oregon Department of Justice, overseen by the attorney general, selects which law firm will get the contract for a given case. To make that decision, it relies on a short list of firms pre-cleared to work for Oregon — a list that DOJ lawyers create with input from the Oregon Treasury Department.

Firms on this short list have the ear of state officials. They can monitor lawsuits and news reports nationwide, and pitch the state on companies it might sue.

And often, while they’re vying for that work, law firms are writing checks.

'YIKES!'

Since 2008, every Oregon treasurer or attorney general has readily accepted the campaign support.

Ted Wheeler, who became treasurer in 2010, took at least $33,000 in contributions from class-action firms or their individual attorneys. Attorney General John Kroger, who pursued lead status in seven class actions while in office, received more than $115,000 in contributions affiliated with law firms, three of which were tapped to represent the state under his watch.

The most recent duo with oversight over class actions have benefited from more generous giving than any of their predecessors.

Rosenblum has accepted at least $141,000 from plaintiffs firms since her first attorney general race in 2012. As of early December, about 18% of the money the attorney general’s reelection campaign reported collecting in 2019 came from out-of-state firms interested in class actions.

Read, meanwhile, has enjoyed more support from firms in the business of class-action suits than any other Oregon elected official. As of Dec. 3, he had reported more than $104,000 from class-action law firms in 2019, accounting for 41% of the $250,418 his campaign had taken in for the year.

In 2018, the same year the state began updating the list of firms eligible to handle cases on Oregon’s behalf, Read accepted $55,000 from many of the same entities — a full 30% of his contributions.

In total, Read has received more than a quarter-million dollars from firms or attorneys with an interest in class-action work, state records show. None of them contributed money to Read’s campaigns in his previous role as a state representative.

Cox, the Duke University professor, expressed alarm when told plaintiffs firms accounted for nearly half of Read’s money in 2019.

“Yikes!” Cox wrote in an email. “Did the Legislature not see this as likely to happen?”

Adam Pritchard, a University of Michigan law professor who has also studied this system, takes a more cynical view of what Forbes once called the "class-action industrial complex."

“There are two motivations, if you are a state politician, to bring securities fraud class actions,” Pritchard said. “One is to reap campaign contributions, and the other is political grandstanding. The two are not mutually exclusive.”

BIG CHECKS, BIGGER REWARDS

State officials who responded to inquiries for this story all insist that campaign contributions play absolutely no role in which law firms win work. Oregon candidates who accept campaign money have made a habit of explicitly walling themselves off from choosing firms, they say.

But for a public already wary about the increasing role of money in Oregon politics, the system might raise questions.

Since 2008, the state has filed 11 class-action lawsuits, according to information supplied by the Department of Justice. In every one of them, the state was represented by an out-of-state firm that — either before it was selected or after — became a major campaign donor in Oregon.

Here’s one example: After the mortgage crisis hit in 2008, Oregon’s pension fund lost $46 million via investments in two financial institutions: Bear Stearns and Countrywide Mortgage-Backed Securities.

Oregon officials believed they’d been misled into investing heavily in the companies, and the size of the state’s losses put it in a prime place to lead class-action suits. So Attorney General Kroger and Treasurer Wheeler filed two lawsuits in 2010. The state chose Washington, D.C., firm Cohen, Milstein, Sellers & Toll to represent its interests.

"Oregon is taking a stand against predatory lenders and the financial wreckage they caused for families and for investors including Oregonians," Wheeler said at the time.

The cases took years to play out in court. In the meantime, Cohen Milstein became an enthusiastic campaign supporter in Oregon.

The law firm donated $10,000 to Kroger in August 2011. Wheeler got a boost, too, pulling in $8,000 from the firm or its employees for his 2012 reelection.

For good measure, Cohen Milstein put $10,000 apiece into the campaigns of Democrats Dwight Holton and Rosenblum, who ran against each other in 2012 to replace Kroger as attorney general.

"There are two motivations, if you are a state politician, to bring securities fraud class actions. One is to reap campaign contributions and the other is political grandstanding. The two are not mutually exclusive."

ADAM Pritchard

University of Michigan professor

In total, the firm and its lawyers have contributed at least $45,625 into attorney general or treasurer races since 2012, and been tapped to represent Oregon in securities class-action suits four separate times.

Those contributions are a pittance compared to what Cohen Milstein has reaped by working for the state.

Out of $1 billion recovered via settlements in the Bear Stearns and Countrywide suits, Cohen Milstein and other firms were awarded around $170 million from the settlement funds — awards that were sought by the firms and approved by a judge. In one of those cases, currently under appeal, Cohen’s attorneys were awarded more than $1,000 an hour.

The firm would not answer questions about its interest in Oregon politics.

ELECTED OFFICIALS SEE NO ISSUE

Rosenblum and Read say the money they’ve taken from out-of-state firms has no bearing on state work.

Each says they keep completely out of the process for selecting firms eligible to work for the state. Attorneys with DOJ and Treasury both participate in vetting applicants for that list, and DOJ has final say.

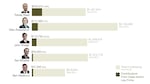

Who Got What?

Every attorney general and state treasurer for the last decade has readily accepted money from class-action firms — money that experts say comes with a perception of "pay to play." Here's a look at money they've received, as a percentage of total contributions.

Source: OreStar

When it comes to selecting a firm to handle a specific lawsuit, Rosenblum and her staff say the attorney general is far removed from any decision.

“I defer and delegate a lot to the really great people in my office, the ones that actually have the expertise in the areas that we pursue,” Rosenblum said. “That's not something that I should be spending my time on and, out of an abundance of caution, I have chosen not to do that.”

Kroger, who currently works for the U.S. Navy, did not respond to inquiries for this story. According to three people who worked for him at DOJ, a similar wall existed. Wheeler, now the mayor of Portland, also did not respond to repeated inquiries about how he handled the process as treasurer.

Read said he takes the matter of walling himself off from selecting law firms seriously. When the state went about reshaping its short list of eligible firms last year, he said both he and his chief of staff were completely in the dark.

“There are a couple of Treasury attorneys who participated in the interview process and that sort of stuff, but the only thing I knew about it was when it was done,” he said.

Read and Rosenblum were also clear on another thing: They actively ask these same firms for money.

“I get lots of support from all over the country, including the law firms that you're referring to,” Rosenblum told OPB. She added: “Most of the money that I bring in to my campaign, I have had some role in soliciting.”

The attorney general declined to say what she tells class-action lawyers when asking for support.

“The fact of the matter is that I do not have any role in choosing these law firms,” she said. “If they choose to give to me, I think that's great.”

Of roughly a dozen class-action firms contacted for this story, just one attorney would speak at length about her contributions: Maya Saxena, a partner at Boca Raton, Florida-based Saxena White. The firm and its employees have donated nearly $45,000 to Oregon candidates since 2016. More than half of that money has gone to Read, and $10,000 has flowed to Rosenblum.

Saxena said in an interview that her firm’s interest in Oregon politics had to do with the national legal landscape — not securing work for herself.

“Oregon has never done a case with us,” she said. “It’s probably a stretch to think that they might.”

In Saxena’s view, class-action suits like those Oregon participates in are under heavy attack from corporate interests and conservative politicians around the country. Her firm decided to get involved in politics several years ago to help counteract that trend. And since Democratic treasurers tend to support class actions, Saxena began giving in their races.

“We want Democratic treasurers in office,” she said. “It’s as simple as that.”

Still, Saxena conceded that big political donations have appeared to correlate with firms receiving work in some places. “We don’t have the money that the bigger firms do that could turn heads,” she said.

Saxena met Rosenblum years ago, and called her “terrific.”

“I love her agenda and I think she’s done a lot of great things and progressive things,” she said.

She’s also met Read through her interactions with a group supporting Democratic treasurers around the country. “He goes to a lot of the same functions, I do,” she said. Saxena didn’t recall Read specifically calling her for money, but said it’s possible.

"The fact of the matter is that I do not have any role in choosing these law firms. If they choose to give to me, I think that's great."

ellen rosenblum

oregon attorney general

When he does pitch firms, Read says they are "very clear" that he'll have no role in actually selecting them for state work. But he said he also makes clear "that I'm interested in availing ourselves of [filing lawsuits] when it makes sense."

Read and Rosenblum both dismissed any suggestion that Oregonians might be suspicious their campaigns are being funded by people who want state business. They argue class-action lawsuits are, first and foremost, a way to battle corporate misdeeds and pry back millions of dollars from powerful interests.

“There are corporations in the world who are doing bad things, who are misrepresenting their behavior, who are tolerating sexual harassment, who are signing customers up for things they didn't want,” Read said. “And there are people out there who are holding them accountable. … If that's the question, I'm happy to have the support of those good guys.”

Not everyone who’s received interest from those good guys is as sanguine about the arrangement.

In 2012, when he was battling Rosenblum in the Democratic primary for attorney general, Dwight Holton received more than $55,000 from securities class-action law firms in a four-month span.

“We had to raise close to a million dollars just in order to be able to get people’s attention,” Holton said recently.

Holton said he made no promises to donors beyond his standard stump speech. Like Read, he believes firms were attracted to his candidacy because he was willing to make use of class actions.

Holton said he, too, intended to wall himself off from any decisions about which firms would handle securities suits if he’d won. But he acknowledged that the situation highlights flaws in Oregon’s laws.

“A better solution would be for the state to place limits that insulated any political influence from that kind of contract,” he said. “It’s part of the reason I’m an advocate for public financing of elections. As soon as you introduce private financing into campaigns, you run a risk of conflict of interest.”

OTHER STATES ARE CRACKING DOWN

In other parts of the country, this wouldn’t be allowed.

A growing number of states are passing “pay-to-play” laws that curtail or outright ban contributions by companies seeking work with a public entity.

In Connecticut, for instance, some of the very firms that are big givers in Oregon — Cohen Milstein and Grant & Eisenhofer — are on a list of companies banned from giving to public officials because of their potential business interest in the state's treasury and justice departments.

At least 20 states and some of the largest cities in the country have adopted rules curtailing giving by potential contractors, though those rules vary wildly from place to place.

"In other states, that's criminal bribery. You go to jail."

dan meek

portland attorney

In North Carolina, when concerns arose that the treasurer’s office was overly cozy with class-action firms, Cox said the state decided to partly remove the treasury from the selection process. The Duke professor was appointed to an advisory board in 2010 that took charge of deciding which law firms would qualify for state work.

“[Oregon] probably ought to have individuals who are totally outside the government arena that formulate that list,” he said.

Even that didn’t wind up quelling controversy in North Carolina; in 2012, the state treasurer faced questions about tapping a New York firm for work after it had donated $75,000 to her campaign. The treasurer, Janet Cowell, defended the move.

In Oregon, even the barest regulation is hard to come by. That stems from a 1997 Oregon Supreme Court ruling that campaign finance limits aren’t allowed under the state constitution.

Voters in two local jurisdictions, Portland and Multnomah County, have approved campaign finance regulations that would eliminate corporate contributions to candidates, among other things. But even if those rules are ultimately enshrined they would have no bearing on statewide races for attorney general or treasurer.

Dan Meek, a Portland attorney who advocates for campaign finance regulation, points out that even the state's bribery laws include protections for campaign contributions. Officials in Oregon aren't allowed to accept or solicit a "pecuniary benefit" in exchange for official actions, but the definition of "pecuniary benefit" explicitly exempts campaign donations.

“Literally in Oregon these firms could go to an office holder or candidate and say, ‘I’ll give you 50 grand if you give me a contract,’” Meek said. “In other states that’s criminal bribery. You go to jail.”

Oregon has seen a renewed interest in establishing some campaign finance rules — a sentiment partly generated by a 2018 gubernatorial race that generated around $40 million in spending.

The state could take a major step in that direction in 2020, when voters will decide whether to modify the constitution to specifically allow for contribution limits. Lawmakers are expected to debate what those limits might look like when they convene next month.

As state treasurer, Read is limited in taking contributions from some interests. Under federal rules, money managers hoping to advise the state on its investments are severely constrained in what they can give him.

Read told OPB he has no problem with those regulations. He also supports campaign finance limits in Oregon. But the treasurer was less supportive when asked whether he would back a pay-to-play law in Oregon similar to what other states have adopted.

“That’s a different conversation to have over the long run, and I’d be willing to entertain that conversation,” he said. “But as the rules are now, I’m OK participating in that way.”

Rosenblum also said she is “strongly in favor of campaign finance reform,” but did not respond to a follow-up question about pay-to-play laws.

“We have to get big money out of politics,” she said. “That’s certainly something that I would look into.”

THE SHORT LIST

Here’s one more example of how the system plays out.

In 2018, as it does at irregular intervals, the Department of Justice decided to modify the list of law firms on the state’s short list for class-action work.

DOJ issued a “request for information” in September 2018 that netted interest from 26 firms. Treasury and DOJ wound up with a list of 18 legal teams eligible to win state work in the future, up from nine on the previous list.

Some were local operations that haven’t had much of a role in Oregon politics. But among the new additions were two firms that have for years have given to both Read and Rosenblum.

One was Saxena White, the Florida-based firm that agreed to an interview for this story. The other was Pomerantz LLP, a New York-based firm that is among the most prolific in the country when it comes to filing securities class actions.

The two firms have given tens of thousands of dollars to Read and Rosenblum. And at the same time they were getting ready to ink a deal to be on the state’s list, Saxena and Pomerantz got out their checkbooks again.

Saxena White or its lawyers gave both Read and Rosenblum $5,000 between June and September of last year. The firm signed an agreement to help the state with possible class-action suits on July 30, 2019.

Pomerantz was more supportive, cutting Read a $25,000 check on June 11, less than two months before it signed an agreement with the state to be on the short list for class-action suits. Attorneys from the firm gave Rosenblum — who has authority to cancel the agreement — $10,000 less than three months after signing.

Money doesn’t always talk, however.

In the recent reshuffle, two firms that have been among the most prolific campaign givers in Oregon — Grant & Eisenhofer and Kessler, Topaz, Meltzer & Check — were taken off the state’s short list.

That might not have been for lack of trying. Records show the two firms gave a combined $35,000 to Read between August and September, not long after the state had signed agreements with other firms.

The reason and timing of those contributions remain hard to pin down.

Grant & Eisenhofer did not respond to repeated inquiries for this story. Darren Check, a principal with Kessler Topaz, did respond to an email. His answer was brief.

“We have no comment,” he wrote, “on our political contributions.”