The state of Oregon has some greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals in place for the next 30 years. Despite this, state emissions are higher than where they should be in order to start meeting the goals.

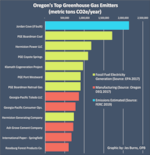

The Jordan Cove liquefied natural gas export terminal and pipeline project proposed for southwest Oregon would not help. If the project gets approved and built, it is projected to become the largest greenhouse gas emitter in the state.

What’s the carbon emissions situation for Jordan Cove?

Total annual expected greenhouse gas emissions in the project footprint are calculated as part of the federal environmental review that happens with projects like Jordan Cove. For Jordan Cove, those emissions amount to 2.14 million metric tons per year in Oregon.

Portland General Electric’s Boardman Power Plant — the only coal-fired power plant in Oregon — emits 1.7 million tons of carbon a year. That’s nearly half a million tons less than Jordan Cove is projected to produce.

Jes Burns, OPB

How do a pipeline and export terminal produce carbon dioxide?

The main way is the “L” aspect of the LNG — liquefying the natural gas. Sending gas across the Pacific Ocean to Asia doesn't make economic sense, so Jordan Cove plans to liquefy the natural gas before loading it onto ships. You can fit about 600 times more natural gas on a tanker as a liquid than as a gas.

One process would purify the natural gas. Massive compressors would then liquefy the natural gas at the terminal site on Coos Bay. Those compressors take a lot of energy to run.

Another compressor station near Klamath Falls would push natural gas from the Rockies and Canada down the 230-mile Pacific Connector Pipeline to the export terminal in Coos Bay.

Jordan Cove would export more than just LNG; it would also burn natural gas to power its equipment. That’s how the bulk of Jordan Cove's carbon emissions would enter the atmosphere and contribute to global warming that is changing our planet's climate.

What does all of this mean for Oregon’s emissions goals?

“It will certainly reverse a lot of work that we have done in the state of Oregon, since our emissions peaked in 1999," said Angus Duncan, chair of Oregon's Global Warming Commission. "We have been able to work those emissions down. And so the LNG facility and the emissions that it would release into the air within the state of Oregon would be a major setback to that progress.”

Oregon has carbon dioxide emissions goals of 51 million tons for 2020 and 14 million tons in 2050. The Oregon Global Warming Commission reported to the Legislature late last year that our current trajectory "does not put Oregon on a path toward achieving its long-term goal," given that in 2017 emissions were nearly 65 million tons.

Part of the reason for the lag, Duncan said, is that the emissions goals are not enforceable.

Jordan Cove’s emissions would represent 4.2% of all greenhouse gas emissions under Oregon’s 2020 goal and a bigger percentage of the 2050 goal.

“This project would constitute a larger and larger proportion of our allowed emissions … while giving no energy to the grid in Oregon,” said Allie Rosenbluth, the campaigns director at Rogue Climate, a grassroots group organizing in opposition to the Jordan Cove LNG project.

As of 2017, the top six industrial emitters in the state were fossil fuel-burning power plants that generate electricity for customers in Oregon and states that share the region's electrical grid.

Backers of the state’s emissions reduction goals achieved a pretty big win when Portland General Electric agreed to close down its coal-fired power plant in Boardman by the end of next year. But if Jordan Cove is approved and built, its carbon pollution would replace what was previously coming out of the PGE coal plant.

Late in 2018, the Oregon Global Warming Commission reported to the Legislature where the state stood on reaching its greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals.

Oregon Global Warming Commission

Would cap and trade affect Jordan Cove's carbon emissions?

As the bill is currently drafted, yes. One way to look at the cap-and-trade legislation is as the missing enforcement piece for Oregon's climate goals. Cap and trade would require large greenhouse gas emitters in the state to eventually shrink their carbon footprint. Jordan Cove would be included. The facility would either have to find a way to limit its carbon emissions (maybe using solar power instead of natural gas to power their facility) or pay for offsets that allow them to continue as is.

“We understand that the future is toward lower-emitting, less carbon-intensive projects, and that states and countries and elsewhere are putting these kinds of regulations into place," said Tasha Cadotte, community affairs manager for Jordan Cove. "We have no issue with it.”

Jordan Cove is owned by Canadian company Pembina, and they have facilities in regions with carbon pricing schemes, so they do have experience there. Cap and trade would likely make operations more expensive for the project.

Are federal regulators looking at Jordan Cove's entire carbon footprint?

The expected direct emissions reported by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is only a small piece of the greenhouse gas emissions linked to the project. But this is where things get a bit squishy.

First, you have to look at the gas before it gets to Jordan Cove, from where it's being produced in the Rockies to the system of pipelines that deliver it to Coos Bay. There's a big concern here about natural gas leaking from pipelines and wells. Natural gas is methane before it's burned. Methane is more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide, as for climate change.

A climate organization called Oil Change International used a middle-of-the-road methane leakage estimate and found the life cycle emissions for Jordan Cove would be about 36.8 million metric tons a year — about 17 times higher than the emissions in Oregon alone.

What about the emissions from LNG after it leaves Oregon?

The burning of liquefied natural gas is by far the largest chunk of emissions associated with the project. Jordan Cove makes the argument that the LNG they’re exporting will actually be replacing some of the coal burned in China to make electricity. And consequently, the global production of CO2 would be less with natural gas in the mix.

“Reducing carbon in the environment is a global goal and it requires global solutions. And I think Oregon can take that as an opportunity to use this project to do that,” Jordan Cove's Cadotte said.

The Oregon Global Warming Commission's Duncan is especially interested in these lifecycle emissions and the overall climate impacts of the Jordan Cove project. He said much of the emphasis examining the impacts of Jordan Cove has been focused on land use questions, like the effect on private property rights.

“In many ways this is sort of typical of our society and economy," Duncan said. "We tend to focus on the foreground. Not that the foreground is unimportant, but the consequences down the road are exponentially more important.”