Miles downstream from the towns and irrigation districts of Central Oregon, the Deschutes River becomes tap water for thousands of people in Warm Springs.

The reservation has the largest community water system operated by a tribe in the Pacific Northwest. Deficiencies at the treatment plant risk people’s health and violate the Safe Drinking Water Act, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. But upgrades will be hugely expensive, and how to pay for them hits a nerve in the community.

At the nearly 40-year-old facility, leaky pipes elbow their way through a dark room where the treatment process begins.

“If we open this hatch right here, there’d be nothing but water down in this pit ... nothing but river water,” said plant engineer Ron Palmer.

He shined a flashlight at the metal grate under his feet. The overhead lights were off, he said, because of an electrical surge a week earlier.

“Us and a house are the only ones out here on the power circuit,” Palmer explained as his narrow beam passed over a pipe stamped "POTABLE."

Warm Springs water treatment plant engineer Ron Palmer stands by the ox bow, a side channel dug into the Deschutes River, where surface water is collected for treatment on Friday, March 29, 2019, in Warm Springs, Ore.

Emily Cureton / OPB

The plant has problems documented for years, many stemming from the challenges of treating surface water and removing river sediment. Two major outages last year heightened scrutiny by the EPA, which sent a violation notice to the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs in March. The Tribe sent back a plan of action, but until the significant issues are corrected, the plant is out of compliance with federal law that protects public water sources.

Warm Springs Chief Operating Officer Alyssa Macy said the water is safe to drink.

“Now, if there are incidents where we have turbidity issues or other issues with the plant, we are required by the EPA to give notice to the community — and we have done that,” Macy said.

Last year, though, plant operators didn’t add the right chemicals to separate solids from the water. According to public records, it took four days before an alert with highly technical language notified residents anything had gone wrong. The next month, a boil water notice went out 24 hours after a main line break, and lasted eight days before crews could get the supplies and assistance needed to fix the line.

“The main line is old. We are very fortunate that it hasn't happened again. But honestly it could,” Macy said. “We have to get our plant to operate the best that it can until we replace it.”

In September 2018, the tribe got about $1 million in federal grants to deal with the imminent threat of a system failure. Macy estimated actually replacing the plant will cost $30 million to $40 million, a figure daunting for any rural community. One key difference between Warm Springs and the town down the road is that in most places, 80% of the water fund to maintain infrastructure comes from billing customers. On the reservation, that revenue stream is next to nil. Only businesses pay for water.

“What we could do differently is we could look at charging a user fee,” Macy said.

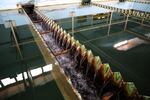

Water that had been settling in a basin flows onto the next phase of treatment at the Warm Springs water treatment plant in Warm Springs, Ore., Friday, March 29, 2019.

Emily Cureton / OPB

Charging tribal communities for water when the system isn’t tied in to a city is uncommon and often unpopular, but it’s not entirely without precedent.

In Alaska, 27 tribes recently formed a rural utility collaborative to centralize the administration of customer billing, expertise and supplies.

Engineer John Warren said it’s been a win for water quality, public health and economic viability.

“We've seen communities that were hundreds of thousands of dollars in the red … and after a few years they are hundreds of thousands of dollars into the black,” said Warren, a director with the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC).

It’s a nonprofit focused on meeting health needs, which estimates roughly 30 villages in rural Alaska still don’t have running water and flushing toilets. While Warren credited the nonprofit with creating sustainability in small-scale systems, the biggest downside to utility collectivization, he said, is cutting off service for non-payment.

“In a very small community, it's difficult. It may be that you're required to cut off your uncle, or your aunt, or your mother. In a lot of cases that doesn't happen, or becomes very difficult to do,” he said.

There are cultural reasons Native people resist and resent paying for water, said ANTHC project manager Marleah LaBelle.

“Historically, tribes lived on the land and were a part of the environment. We had our own uses of water, through subsistence or personal use and also a connection through ceremony,” she said. “This notion that it's something to be paid for, something that somebody owns, is really different.”

In a kitchen on the Warm Springs reservation, the idea of paying to get clean water exasperates 81-year-old tribal member Arlita Rhoan.

“How are they going to charge water to people” who can barely afford their homes, Rhoan exclaimed.

She said her home won’t be paid off until 2023, even though it hasn’t had any significant updates in decades. She’s skeptical of what’s in the pipes, and dislikes the tap water’s chlorine smell. “We just go ahead and use it. Your food smells, tastes like — I don’t care how much seasoning you put it in, it still tastes like that water.”

Arlita Rhoan, right, and Lyle Rhoan stand in their kitchen on the Warm Springs Reservation on Thursday, March 28, 2019, in Warm Springs, Ore.

Emily Cureton / OPB

Rhoan grew up collecting water from springs and creeks on the reservation. She remembers a little black bug was her original indicator of water quality; if the bug lived in the stream, it was good to drink. She said she has watched over the decades as water quality degrades with upstream development and climate change.

“Suppose they start charging us for water, then our water really gets contaminated. Then what?” she asked.

She drinks from the tap using her one special coffee cup, which stays perched on a window sill above the kitchen sink. Rhoan said she ignored the latest boil water notices, and to her, a familiar source is always more trustworthy than a foreign one.

“I buy water when we're traveling. I will not trust other cities’ water,” she said.

The city of Bend quit taking its drinking water straight out of the Deschutes before Rhoan was born. A hundred years ago, flooding reservoirs for irrigation let loose contaminants, and health officials declared the river unfit for human consumption.

The tribe advocates for its treaty rights through a Natural Resources Department, with Bobby Brunoe at its head.

“To this day people are very aware of water and how important it is to us, because it’s in all our ceremonies and embedded in our culture,” Brunoe said, describing how ceremonies always begin with a drink and a prayer.

“We are the oldest water right in the Deschutes Basin, back to time immemorial.”

That seniority hasn’t stopped diversions upriver, where most of the flow is redirected before it reaches the reservation, its aging infrastructure and those struggling with the cost of replacing it.

Meanwhile, the tribe’s water treatment plant on the Deschutes risks costly EPA fines. According to a statement from the agency, its “enforcement and compliance role is geared to first working with the tribal governments … through offering technical assistance.” However, “If attempts to fix acknowledged problems using this approach fail to produce desired results, persistent problems frequently prompt additional enforcement actions.”

The Warm Springs water treatment plant sits at the end of a remote gravel road dotted with roving cattle on Friday, March 29, 2019, in Warm Springs, Ore.

Emily Cureton / OPB

For the last 70 years a different, non-regulatory federal agency has been involved in developing tribal sanitation systems, including the ones in Warm Springs. Indian Health Services (IHS) has one of nine federal assistance programs for drinking water infrastructure on tribal lands.

“Our program and our projects are aimed at helping the tribes utilize the resources that we have and access resources from other funding partners or their own budgets to improve and solve the challenges they face,” said Capt. Mathew Martinson, an engineer with IHS covering Oregon, Washington, Idaho and part of Utah.

He said available money pales in comparison to need. In 2019, the area encompassing 43 tribes in the Northwest got $4 million from Congress to build sanitation facilities. Priority projects required six times that amount, Martinson said. Nationally, the disparity is bigger, according to figures provided by the Portland area IHS office. That means only the most derelict systems make the cut.

“Warm Springs is a significant focus of our team and our team resources,” Martinson said, declining to elaborate on exactly where the tribe’s need was ranked.

He said work has begun on a “substantial engineering report” that will put a new drinking water treatment plant in line for future funding.