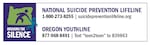

Editor’s note: This story is part of Breaking the Silence, a week-long effort by news organizations across Oregon to change the way we talk about the public health crisis of death by suicide. It contains descriptions of suicide and may not be suitable for all readers. If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, call for help now. The National Suicide Prevention Hotline is a free service answered by trained staff 24 hours per day, every day. The number is 1-800-273-8255. Or text 273TALK to 839863.

Gabe Willitts loved the outdoors. He had friends all around town in Sisters, Oregon, where he grew up. He graduated from Sisters High School in 2015 and left town for college in Colorado.

In May 2018, he took his own life. The family was heartbroken.

“He was incredible, just an incredible human being,” said Bill Willitts, Gabe’s grandfather. “Heartful, beautiful.”

Bill is a Sisters institution. His family built the Five Pines Lodge, a hotel near the edge of town. He’s been in Sisters for over 20 years, and he and his wife, Zoe, live in an old building that used to belong to the Oregon Department of Forestry.

Soon after Gabe’s death, Willitts had dinner with friends who helped out with his grandson’s service. They talked about suicide.

“So I said, 'What can we do?' Then we began to do research, and we drew people together,” Willitts explained.

Willitts and eight prominent members of the community became Fortitude. The group includes the school district superintendent and an organizer of the Sisters Folk Festival.

The group started meeting, figuring out a way to engage the Sisters community – “from 3 to 93,” says Willitts – in efforts to prevent suicide and raise awareness.

Then Galen died.

Galen Boles, 22, was from Sisters and a friend of Gabe’s.

“We worry about each one of them, we love each one of them,” said Willitts. “Galen, I think, underlined [our] worst fear.”

Both boys attended Sisters High School, where Fortitude member Heather Johnson is the only health teacher. Over the years, she’s seen students struggle.

“Our students are more stressed than they've ever been,” said Johnson. “There's just a lot more pressure; there’s definitely more and more circumstances of anxiety and depression than I’ve ever seen — and I’ve been in this field for 24 years.”

Johnson sits in her classroom before her first class of the day. Her efforts to make students comfortable are everywhere. A couch lines one side of the room, and a corner is Johnson’s dedicated “hydration station” — full of tea to help students relax.

As the Sisters community grieved the loss of Gabe and Galen, Johnson says a movement started.

After his grandson Gabe died by suicide in 2018, Sisters resident Bill Willitts started working to raise suicide awareness.

Elizabeth Miller / OPB

“It was really amazing to see how our schools and how our community, how our churches, how everyone came together and recognized that this is important,” said Johnson. “No more, not on our watch, no more.”

From Reluctance To Response And Resources

For Johnson, this way of openly talking about suicide is new.

“When I think about how I was raised and in my generation, I was raised by my parents and grandparents where you didn’t talk about stuff like that,” said Johnson. “Anything uncomfortable was always brushed under the rug.”

She says that’s changing, and conversations around mental health are seen as essential.

“How we’ve done it all these years is not healthy at all,” said Johnson.

There’s a county-wide effort to normalize these kinds of conversations.

Whitney Schumacher is the Suicide Prevention Coordinator for Deschutes County. She makes sure communities in her district know about the training and resources available to them.

Deschutes’ suicide rate has increased, according to state data. In 2016, the suicide death rate in the county was 17.80 deaths per 100,000 people. One year later, that number was 29 per 100,000.

Schumacher’s office is hosting parent nights for students in the county’s school districts this year. Unlike similar events two years ago, the new events include information about what to do after a suicide or sudden loss in a community.

“We want to make sure conversation around mental health was normalized — in the home, in schools, in our community,” said Schumacher. “We really try to hone in on the fact that there are resources for anybody in Deschutes County in Central Oregon.”

There has long been a stigma around mental illness. “I think that’s changing with younger generations,” said Schumacher.

But for current Sisters High School students, sometimes seeking help in a small town carries its own stigma.

The 'Pressure To Be Perfect'

Sophomore Skylar Wilkins and her younger sister, freshman Sydney Wilkins, are three-sport athletes at Sisters High. They say an academic schedule and the expectations to do multiple activities adds to the stress.

“You’ve got to have this laundry list of stuff you do,” said Skylar. “It's difficult to do that … but then when you have mental health weighing down on you, that’s a big battle that people don’t see and people don’t count for.”

Sisters High School students Sydney and Skylar Wilkins stand with health teacher Heather Johnson (center). "Our students are more stressed than they’ve ever been,” Johnson says.

Elizabeth Miller / OPB

The Wilkins sisters say they feel pressure from constantly comparing themselves to their classmates.

Both Sydney and Skylar talk to their parents about mental health difficulties, and they have friends they can reach out to for support. But Skylar says it can be hard to talk about mental health in a small town.

“News travels because everyone knows everything,” said Skylar Wilkins. “There’s a certain facade you have to keep up as a student, as a member of the community. It’s like, 'We’re all normal.'”

The sisters didn’t know the two young men who died last year.

But Sisters is small — an old babysitter was Galen’s best friend, says Sydney. The losses made her think about the people she did know.

“When something like a suicide happens, you're kind of forced to open your eyes and say this person I care about is struggling,” said Sydney. “This is something that could genuinely happen and that’s terrifying.”

Sydney Wilkins holds a card for the 24-hour crisis line — she keeps it in her phone case.

Elizabeth Miller / OPB

She’s been there for friends in crisis. Tucked inside her phone case, she carries a card with the crisis hotline number.

“I like carrying that around because I know I’m not always going to be able to help this person,” explained Sydney. “But it’s easier to come to me than to go to someone you don’t know.”

Finding Sources Of Strength

Fortitude is launching its first initiative this fall, called Sources of Strength. It’s a suicide prevention program that will train students to be peer leaders and create campaigns for safe messaging around hope and helping students who may be feeling suicidal.

Bill Willitts wants to build mental health resiliency for kids if they decide to leave home.

“You're going to go out and this world is going to get really difficult — we're going to help you build tools so you're ready,” said Willitts.

A Tree of Positivity grows at Sisters High School.

Elizabeth Miller / OPB

Fortitude plans to spend the next year working on community outreach, with the goal of figuring out where the community is when it comes to talking about suicide and mental health.

The group worked with the school district superintendent to make sure mental health priorities are equal to academic ones.

It’s all a part of Willitts’ goal: for Sisters students to develop “tools” starting as early as kindergarten.

“I don't want to see another parent, another grandparent, suffer what we're suffering,” Willitts said. “I will forever, as long as my life continues, miss Gabe. I loved him deeply. But what can I do about that? I can help others.”