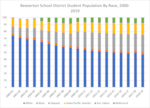

Beaverton is changing. Over the last 19 years, Beaverton schools have become more diverse, with students of color now making up 53% of the student body. In 2000, they were 26%.

Beaverton schools like Southridge have changed over the past several years.

Elizabeth Miller / OPB

Nowhere has this change been more evident than Southridge High School. In addition to changes across the district, a few years ago boundary changes drastically changed where students attended school. Southridge suddenly became more diverse racially and economically.

“Roughly 40% of our student body was brand new to us,” principal David Nieslanik said.

Districtwide, the biggest demographic change has been with Latino students, who are now a quarter of Beaverton’s school population.

Hundreds of students, staff and community from around Beaverton showed up to Southridge for a community-wide conversation, including sessions on race and gender, race in the classroom and addressing white supremacy.

OPB spoke with five students and a staff member who shared their experiences of growing up Latino in Beaverton at the meeting.

Growing Up Latino

Evelin came to the United States when she was five. The only English words she knew were “yes” and “no.” As she recalled, she started school two months after arriving in the country.

“I could never make friends, it was really hard,” Evelin said. “I could only speak Spanish.”

Like Evelin, Jesica came to Beaverton from Mexico around the time she’d be just starting school. And for her, the experience was intimidating.

Beaverton schools have become more racially diverse over the last 19 years. Data show the growing percentages of Hispanic, multiracial and Asian/Pacific Islander students.

Data courtesy of Beaverton School District

“Coming to a different country where I was exposed to a different culture, different language and everything, it was just hard and scary because I would always think I was being judged by everyone,” Jesica, now a senior at Southridge, said.

For both Jesica and sophomore Bri, moving from neighborhood to neighborhood within Beaverton was a culture shock of its own.

“We were with our own people,” Bri said, recalling her experience as a little kid in Beaverton. “If you needed a lemon, you would go to the neighbor and you would knock on their door … If one kid got lice, everybody else got lice, that type of community.”

In seventh grade, she moved and things changed. Her family didn’t have the same comfortable relationship with neighbors. At school, Bri could speak English well, but writing remained a struggle.

She had friends, but she and others were labeled as the “Mexican girls” – though that didn’t represent all the different cultures and countries their families had come from.

She felt alone and inadequate at school, and it affected her academically and personally.

“There was a point where I was like, ‘I want to be white,’” Bri said. “I bleached my hair blonde, I refused to speak Spanish in front of everybody that whole eighth-grade year … It was hard for me. I didn’t come to school, they almost disenrolled me because I didn’t come to school for three months.

Schools can "disenroll" students from school if they've missed a long stretch of school. It means the school has concluded the student isn't coming back — and re-enrolling can be difficult.

Southridge senior Alma had a rough time in middle school, too.

“When I finally got my little phone, I would look up, ‘How to lighten up my skin tone’ because I hated my skin tone so much,” Alma said.

But then she met Evelin. As she teared up, Alma spoke about how valued she feels by her friends and her high school experience.

“She was my first best friend that I could really connect to,” Alma said. “Coming to Southridge and seeing the difference and the school do these things to involve all races is so amazing and it feels so wonderful and beautiful that they get to do that for us.”

A Changing Southridge

Southridge is about three years into a dedicated effort to talk about race and support its more diverse student body. The first year was about transition, but now Nieslanik is focused on building community.

He requires every staff member to participate in book groups related to race. He said the school is working on better, more inclusive approaches to teaching.

A recent summit on race at Southridge High School centered students of color as the keynote speakers.

Elizabeth Miller / OPB

“If we don't provide a venue that is safe, a venue that is inclusive, that also guides conversation, then we're not serving our students well,” Nieslanik said.

At the district-wide meeting last month, attendees gathered for the keynote – a student panel in the center of the school’s “fishbowl.” Five students representing different backgrounds and schools sat on beanbags and couches and talked while the audience listened.

“We have these conversations so often as students, but once it’s brought up to staff, it’s often ignored and not taken seriously, or it doesn’t move past a conversation,” said one student on the panel. “It never turns into action – which can be so frustrating because I’ve been talking about this thing for 13 years, since I was a toddler.”

Nieslanik said someone from every Beaverton high school attended the meeting, plus some teachers and administrators from elementary and middle schools.

Districts around the country continue to talk about race and equity. Often, officials are reacting. They lead conversations following a hate incident or have discussions because they're mandated by a grant or directive from a state or federal official.

Nielsanik’s advice for districts? First, provide definitions and explanations around words. Second, listen to students and parents and involve them in the process. And lastly, take it slow.

Hundreds of students, parents and staff members attended a recent district-wide meeting about race at Southridge High School, in Beaverton, Ore.

Elizabeth Miller / OPB

“Our students need for this conversation to happen and our staff need for this conversation to happen,” Nieslanik said.

Students appreciate how Nieslanik encourages conversations about race – and conversations led by students.

“He’s even educating himself,” Bri said. “He’s not trying to use his voice to say the same thing I’m saying, he’s giving me a space and a platform.”

A Supportive Environment

Maria Vega graduated from Southridge in 2013, before the boundary change shifted student demographics. For her, growing up in Beaverton and going to majority-white schools wasn’t easy.

“It’s been beautiful, but it’s also been a struggle being a person of color,” Vega said. “Especially for my parents – I don’t think my mom has ever stepped foot in this school, and I was here all four years — just because she felt like she didn’t have the help and also because they had two jobs.”

But now Vega is back at Southridge as a counseling secretary. And she’s happy to be a source of support and inspiration for students, just like a former Southridge counselor she valued.

“She showed me that – I felt that I had that one person at Southridge that I could go to for guidance,” Vega said.

Today there are two Spanish-speaking people in the office to help families, plus other Latino staff and teachers.

Evelin arrived at Southridge before the boundary changes. But in the years since, she’s noticed an effort to help Latino students and their families.

“Maria, Ms. Miriam [Ramirez, a bilingual facilitator at the school], and everybody else have done a great job of including the Latino families and I just feel super welcome, and so does my mom,” Evelin said.

Future Generations

The student body at Southridge continues to change. This year’s freshman class was the first “minority-majority” at the school, with more students of color than white students.

Jose, a junior at Southridge, grew up in Beaverton, going to mostly white schools.

Jose and Evelin credit a group called MEChA for helping them become more comfortable at school.

MEChA, or Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan, is a student-led club with chapters all over the country. At Southridge, MEChA students watch documentaries and host dances. The club also provides leadership opportunities for the school’s Latino students.

As the vice president of MEChA, Jose jokes that he lives at school because he’s so involved.

He never had Mexican or Latino teachers growing up – but he wants to be that for the next generation of kids coming up through Beaverton schools.

“That’s my goal — to come here, come back, help either Southridge or Beaverton … any school in the district to be a better district for me and my future kids,” Jose said.

That’s a challenge widely recognized at schools across Oregon, including at Southridge. The large high school has only six teachers of color. Nieslanik recognized the need to hire more diverse staff – for him, that means making sure more students of color go into teacher training programs.

Like Jose, Bri sees herself as working for future students, like her sister in sixth grade.

“It’s hard for us to do it, but it’s going to pay off so much when my little sister comes here,” Bri said.

But students suggest the work isn't done when it comes to making Southridge a comfortable and supportive environment for students of color. Bri said sometimes, racial equity ends up competing for attention in the classroom. But it’s still at the top of her list.

“A lot of people told me in my AP class, why are we having another conversation about race? Why can’t we talk about climate change?” Bri said. “I want to talk about climate change. I totally want to talk about climate change. But I’ll talk about climate change the minute they see me as a human being.”