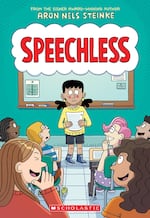

"Speechless" is a graphic novel which was published in March 2025 and written and illustrated by Aron Nels Steinke, the award-winning Portland author and illustrator of the "Mr. Wolf's Class" book series.

Courtesy Aron Nels Steinke / Scholastic

Award-winning Portland author and illustrator Aron Nels Steinke is perhaps best known for his “Mr. Wolf’s Class” series of graphic novels which revolve around a teacher — who happens to be a wolf — and his fourth grade class of anthropomorphized animal students. Steinke drew from his experience as a teacher at Portland’s Woodstock Elementary School for that series.

Now, with his new book, he’s drawing from his personal experience as an adolescent student who struggled with social anxiety. “Speechless” tells the story of Mira, a sixth grader who has selective mutism, an anxiety disorder which prevents people from speaking in certain social situations, such as in front of a class. The graphic novel explores the messy feelings and turns and twists of relationships during adolescence, on top of the struggle to find your voice. Aron Nels Steinke joins us to talk about “Speechless.”

Note: The following transcript was transcribed digitally and validated for accuracy, readability and formatting by an OPB volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. Award-winning Portland author and illustrator Aron Nels Steinke is perhaps best known for his “Mr. Wolf’s Class” series. The graphic novels revolve around a spunky and diverse fourth grade class. Steinke drew from his own experience as a teacher at Portland’s Woodstock Elementary School for the series.

He drew from a different kind of experience for his new book. It is a stand-alone graphic novel called “Speechless.” It tells the story of Mira, a sixth grader who has selective mutism. It’s an anxiety disorder that can prevent people from speaking in certain social situations. In an author’s note at the end of the book, Steinke writes that he, too, dealt with social anxiety when he was growing up.

Aron Nels Steinke, welcome back to Think Out Loud.

Aron Nels Steinke: Thank you, Dave.

Miller: Can you introduce us to Mira, the main character in the book?

Steinke: Yeah. She is, like you said, a sixth grader. She’s starting her first day of middle school, and she really wants to make a big leap on the first day of school and start speaking. She has this anxiety disorder where she doesn’t speak in school, but she speaks just fine at home. But she really wants to speak in school. So even though she doesn’t speak, it’s not like a choice, this is … and I think that the term “selective mutism” is one that is the widely accepted term. I prefer “situational mutism,” where you’re in a situation that creates anxiety and that’s what causes the inability to speak.

Miller: What made you decide to write a whole book about this, with this as one of the major themes?

Steinke: Well, that’s a tricky question to answer. I think, starting back from when I was teaching elementary school, I did work with a student who didn’t speak at all in school and that was a little eye opening to me. I didn’t work with him directly all the time. Once in a while I would work with him and discovered the term “selective mutism.” I don’t know what that student was really diagnosed with. I don’t know if they had a different reason for the mutism, but once I learned about selective mutism, I strongly identified.

I realized that – whether or not I would have been diagnosed as a kid, I don’t know – I have a lot of anxiety, myself, and it sometimes causes me to either trip over my words or make me feel like I need to retreat, just hide in a shell and not speak at all.

Miller: It seems like that would have been impossible when you were a teacher. Did that anxiety pop up when you were in front of a class as an adult, years later?

Steinke: Never with children, no. I’m so comfortable around kids …

Miller: So many adults are the opposite – and I feel this. I think I’ve gotten better, having kids, but when I first had to interview kids, it seemed terrifying. But you didn’t feel any kind of a version of social anxiety among kids?

Steinke: No, I didn’t. And there was even a moment where, when I was writing the story, I had [thought], through my own workings as a therapist – I’m not a therapist, but I imagine what a therapist might do – working with younger children would have been a really great thing for the student to do, to actually build up that confidence just like I have built up confidence working with children as well. That didn’t make it into the book …

Miller: If Mira could have been a mentor to a first grader.

Steinke: Yes, like in elementary school, we often have reading buddies, where you’ll partner with a younger group, and I could see that being a really great entryway for her. I wish I had that moment in the book. IKt didn’t make it into the book. The focus became more on her expressing herself through creativity, getting some tips and tools from her therapist, and working with kids her own age.

Miller: Can you describe the particular creativity that Mira has, what her passion is?

Steinke: Mira is a stop motion animator. Being in Portland, Oregon, we’re the unofficial capital of stop motion animation in the world. And I thought that would be a great connection to something that is local, but also something I’m interested in, too. I studied hand-drawn animation when I was maybe 18. I started getting into that. I went to school for it and didn’t learn stop motion until around 2019 and 2020.

They were making the movie, “Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio.” My son and I both got a tour of the studios and got to see puppet fabrication and scene fabrication. It was really, really cool and I wanted to do that myself. So during the pandemic, I learned how to make my own stop motion puppets and started filming stop motion. My son is a really big influence. He was kind of my muse for this book. He is a filmmaker himself and he’s 12, almost 13. But he makes his own films, and I channeled that personality and energy into the character Mira, coupled with my own anxiety.

Miller: What does art mean to Mira?

Steinke: It means so much to her, just like it means a lot to me. This is how I process my thoughts and feelings. At the beginning of the book, Mira has a really hard day. It doesn’t go as well as she wants it to go. She isn’t able to speak on the first day of school. So when she comes home she sets up a scene, she makes this little clay tomato called “Tommy Tomato,” and she films a little film that has this dinosaur squash Tommy Tomato. And I bet it felt pretty good for her to have that experience; to cathartically take her energy and maybe even self-hatred out on a little clay anthropomorphic tomato.

She uses art as therapy and, again, that’s what I do. I’ve always done … as a way to process my own emotions and it makes me feel better. And I think it makes her feel a lot better, too. It’s not enough, so she does see a real therapist, but it is something that she’s coping with on her own.

Miller: You say that’s what you do, what you’ve always done. When you were 10, 11, you would make art as a way to both make sense of the world but also to feel better about your place in it … or am I putting words in your mouth now?

Steinke: No, you’re … I said, “always,” and I think I need to edit that. I would say since my early twenties. As a kid, I was probably more focused on sports and video games, and that was my outlet. But as an adult, once I started going out to meet people, I would go to coffee shops or a bar, and I would bring my sketchbook with me, and I would draw. That was a great way to facilitate conversation. And if I was having a bad day, I would draw these comics in my sketchbook.

Actually, I’m most well-known for my “Mr. Wolf’s Class” character, the Mr. Wolf character, who’s this really respectable, respectful teacher, a warm, inviting character. He actually started out in my sketchbooks as an angry version of me. He had sharp teeth, and he didn’t dress up as a teacher. He exemplified my anger and stuff, those are the correct words I’m using.

Miller: But when it came time for a series about an actual teacher, you realized you would make him more respectable, kinder and less tooth-baring?

Steinke: Yeah, he became that. He evolved naturally. As I became a teacher, I started feeling better about my life because I had a job that could support me and purpose. I was working with awesome kids every day, so I naturally just [let] all that, I guess, disappointment in my own life cool off and I was less angry.

Miller: One of the things that I loved and respected about Mira is how weird her animation is. She’s making absurdist stuff and then she’s releasing it into the world in an anonymous way. So all the kids, including the older kids, the eighth graders, have no idea who the artist is, but they like it even though it’s truly weird stuff.

Steinke: Yeah, I created it, so it is of my mind. I didn’t think too much about …

Miller: What I mean by “weird,” it’s not a straight-ahead narrative, necessarily. There are weirder things that are happening.

Steinke: Yeah, I think she’s following her intuition, and I was too. I wasn’t really even aware when I made her. Throughout the book, you do see the films that she’s making, and you look at them as being her processing her thoughts and feelings. They are abstract, they’re kind of strange and they have weird creatures, but they’re also fun and silly. A big part of that is just having fun and making weird animation.

Miller: The characters in “Speechless” are a little bit older than in “Mr. Wolf’s Class.” Are the intended readers a little bit older as well?

Steinke: Yeah, the intended readers are slightly older, so there should be some overlap with “Mr. Wolf’s Class.” “Mr. Wolf’s Class” tends to get a wide range of readers. I have preschoolers and even younger than preschool kids that are read the books by their parents. The kids have dreams about these characters and it’s really flattering.

And then I have kids who’ve been reading the “Mr. Wolf’s Class” series ever since they first started coming out. And they’re in middle school. Sometimes I’ll get a high-schooler who still has nostalgia for the series – and its bananas. But really, it’s like age 7 to 11 is “Mr. Wolf’s Class,” and age 8 to 12 is “Speechless,” if you want to go by the way the publisher puts out the recommendation.

Miller: Does that affect the way you write?

Steinke: It does. I think with “Speechless,” I got to get a little darker. It was fun to be a little darker. I always have humor in my books, I always want them to be funny. And even just looking at the characters, they’re silly. Through cartooning, my style just naturally has a levity to it, but with the “Mr. Wolf’s Class” stuff, it’s less dense, it’s more “slice of life”-ish, and it’s an ensemble. It’s about the silly things that happen in the classroom. There could be anxiety that I explore, but it’s not going to go as deep as this book, with “Speechless.”

Miller: At the end of your acknowledgements, you thank “all the teachers, librarians and educators doing your best to listen to students,” writing, “kids often just need someone to listen to them.” That’s literally the last line of the book. Why did you want to include that?

Steinke: Oh, I’m so glad you pulled that out. I forgot all about that. I think that has been a major source of my anxiety about speaking in certain social situations in my life, is where we’re afraid of being not listened to, or being cut off, or dismissed, or made fun of – and that’s my anxiety.

In the classroom, all children just want to be seen and heard. They just want to have their voice heard. And oftentimes, you might be working in a classroom and a kid just really just needs you to hear them for a moment. Then everything is going to be much better throughout the day.

The challenge is being a teacher, having so many students in your classroom and being able to give them that audience. The great teachers find ways to make that happen, are patient, and make structures in their classrooms so students can talk and get their voices heard.

Miller: But there’s also, to me, a fascinating paradox, because it seems that one of the reasons for selective or situational mutism is the fear that if you talk, someone’s gonna listen, someone’s gonna hear you. But you’re talking about the fact that being listened to, being taken seriously, being respected, being really paid attention to, is also part of the solution. It’s a paradox.

Steinke: Absolutely. I think there’s also a lot of intersectionality between reasons why someone might not be speaking. I think there’s a couple different things that are true for me, and sensorial things are a part of it. But I think what we’re talking about here is being comfortable and being in a safe place. If you have a teacher that you feel comfortable with, that you feel safe with, you’re much more likely to be vulnerable and speak. If you know that you’re not going to get made fun of, teased or dismissed.

Imagine being that student in the classroom who, a teacher called on them, and they were brave, they spoke up and they said something, and the teacher either didn’t listen to them, ignored them. There’s so much room in that power dynamic for kids to just shut down.

So I’ll say one more thing. Even though this book definitely focuses on a kid with situational mutism, selective mutism, I think it’s pretty broad in its appeal to people who stutter, people who have any kind of anxiety over how they’re perceived, is gonna find some comfort in this book.

Miller: There’s a really powerful line near the end. It comes from Mira’s therapist, who is talking about the progress that Mira is making talking in class, talking with other classmates. She says, “it sounds like you’re getting more comfortable with being uncomfortable,” which strikes me now, as you’re talking about the gift of students being made to feel welcome, made to feel comfortable by teachers or by their classmates. Where did that line come from?

Steinke: I think I have to attribute it to my cousin Angie, Angela Stewart, who is a child psychologist. I had her read my book, to go over it as a clinical psychologist for children. And she …

Miller: She’d be a handy thing to have as a reader in the family.

Steinke: It sure is. It’s good to have other readers who are experts in their field. I’m not an expert in situational mutism or selective mutism. So she read it and she did mention something about moving through discomfort and teaching kids that they’re gonna be uncomfortable, and here’s some tips and tools to go through it.

Miller: What have you heard from early readers of this book since it’s been out in the world? When I say early, I don’t mean a cousin who’s a psychologist, but I mean young ones.

Steinke: The book has been out since March 4, so I’ve heard a lot from people. Mostly because my audience is younger, they’re not necessarily on social media, I don’t usually hear from them directly. It’s usually from parents, caregivers, teachers or librarians who are sharing: “This book meant so much to me because my kid has anxiety, and they felt a lot of comfort in it. They’ve read the book two or three times.” I’ve heard from kids who’ve read it, who just loved it. There’s a thing where you see them dive into a graphic novel, read it multiple times and get multiple meanings out of it. They see more and more as they read it.

I think I’ve heard most from adults though, and it’s been really heartwarming and feels really good. I feel like the book has been received really well. I feel like “mission accomplished.”

Miller: When we last had you on the show in 2019, you were still teaching elementary school. Your bio now says you’re a former teacher. Do you miss anything about teaching?

Steinke: Absolutely. I miss being with the kids. You know, there’s a thing, I’m comfortable around kids. I feel like I’ve always identified with kids and been critical of adults who dismiss their intelligence and their emotional intelligence. So I really enjoyed that. I enjoyed being with that community. I miss my colleagues, I miss my co-workers. I miss the learning. As an elementary school teacher, you get to learn stuff constantly. And I imagine, as the host of Think Out Loud, you are learning things constantly too.

Miller: If I had a good memory, I would know a lot right now.

Steinke: It’s a really great thing to have that, because not everybody gets to be challenged like that all the time and it feels really good. I don’t miss grading. I really don’t miss report cards, grading, progress reports. I don’t miss that at all.

[Laughter]

Miller: The smile on your face is very broad right now as you’re saying that. Just briefly, is another “Mr. Wolf’s Class” on the way?

Steinke: Yes, I am working on “Mr. Wolf’s Class” number six. It’s called “The New Student,” and I get to explore some more kid dynamics. There’s a kid who may or may not be telling the truth all the time, and they’re the new student, and how they fit into the new classroom. So I’m working on that. It comes out next August, 2026. I’ve got to wait over a year.

Miller: Aron, thanks very much and congratulations.

Steinke: Thank you, Dave.

Miller: That’s Aron Nels Steinke. His new book, a stand-alone graphic novel, is called “Speechless.”

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.