Dear Reader,

For more than 100 years, OPB has offered reliable news and connection. Through wildfires, elections and economic downturns, OPB has been there to inform and connect our communities. Today, journalism faces new obstacles.

But this work is only possible because of people like you — readers who turn to articles like this and continue to engage with independent journalism in our community. If OPB has been a part of your life, if it has helped you see your community or the world more clearly, please consider making a contribution today.

— The OPB Team

Please select an amount to give. Your contribution ensures that fact-based reporting, cultural connection, and stories that strengthen our community remain freely available to everyone.

Dennett Taber’s daughter was a single mother of four when she left her youngest child in Taber’s care.

Taber recalled her daughter packing her belongings in Salem to drive home to Tennessee. Her baby had lived full-time in Taber’s home since she was three weeks old.

The mother resigned to leaving the toddler with Taber when she left, later saying, “There was no room in the car for the baby.”

Taber was 52 at the time and newly re-married; she had no plans to parent again. But there she was, fully in charge of an 18-month-old.

“We’d only been married for four years, and we talked about it. He said, ‘You know, I really want to give this kid a chance,’ ” Taber remembered of her late husband, Bill Fink.

“And I said, you know, ‘I just don’t want to raise another child … I know what raising kids can do to a relationship. I’ve been there.’

“He said, ‘No, I think we can make this work.’”

Dennett Taber stands for a portrait in her home on Jan. 10, 2025, in Salem, Oregon. Taber helps other grandparents raising grandkids through a new support group at the Family YMCA of Marion and Polk Counties.

Natalie Pate / OPB

Across the United States, grandparents were raising roughly 2.7 million children, according to 2021 survey data shared by the U.S. Department of Labor. That means the child lives with at least one grandparent responsible for most of their basic needs.

In Oregon and Washington, more than 67,000 children younger than 18 were being raised by a grandparent, according to the same 2021 data.

These family structures arise when the parents are unable or unwilling to care for their children. Several factors can lead families to this situation, including financial hardship, substance use, incarceration, death, illness, custody battles and military deployments.

Some grandparents live with their children and grandchildren in multi-generational households. Some are the primary caregivers briefly, while others provide care throughout their childhood. That was the case for Taber.

She remembered early conversations with her grandchild. “I just said, ‘...It’s not that she doesn’t love you. She’s just not able to do it.’

“And that’s kind of a nebulous answer. But,” she paused and shrugged, acknowledging the child might not have really understood, “... it was what I could come up with.”

Now, two decades later and with her grandchild grown, Taber is helping others through the same situation.

Looking for guidance in an unexpected role

Taber didn’t want to disclose the names of her daughter or grandchild. She said a lot of shame and guilt comes from a role like hers — Did she fail her daughter? Did she make the right choices for the child? And she doesn’t want to diminish the progress her daughter has made over the years, either.

“It’s all very emotional and disturbing,” Taber said, “and you don’t know if you’re really doing the right thing.”

By taking in their grandchild, Taber and her husband gave up some comforts and freedoms that come later in life. She delayed promotions at work. They both expended energy they weren’t sure they had anymore, and they figured out how to support their grandchild through life-or-death situations.

Taber and Fink grieved other changes, too.

“When you’re grandma and grandpa, you love ’em, you spoil ’em, and you send them home,” Taber said. “But when you’re raising them, you can’t do that anymore. And that’s kind of sad to lose.”

She now looks back and sees the benefits of raising a child later in life, too. She had more wisdom and life experience the second time around. She and her husband were more financially stable.

So when Valerie Geer, the Community Outreach Chaplain at the Family YMCA of Marion and Polk Counties in Salem, approached Taber about starting a grandparent caregiver support group, Taber jumped at the chance.

“It’s so important for people that are raising children that they didn’t expect to raise to have some support and know that they’re not out there alone,” Taber said.

An infographic depicting how many children were being raised by grandparents according to 2021 survey data shared by the U.S. Department of Labor. In Oregon and Washington, grandparents were raising more than 67,000 children younger than 18 that year.

Sukhjot Sal, John Hill / OPB

Grandparents Raising Grandkids is a new support and resource group for older adults who are the primary caregivers for their grandchildren or other young relatives. They call these unexpected pairings “grandfamilies” or “kinship” families.

The group’s purpose, as they explained to OPB, is to provide a welcoming, safe, supportive and confidential space to process the challenges and opportunities facing them.

It’s only a few months old, and Geer and Taber are working to get more people to join.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re the actual parent or not — raising children can be difficult,” Taber said. “You want people that understand.”

Taking in a child

Taber’s daughter had no money. She was going through a divorce and had substance abuse issues. She had two older kids and another child still in diapers when her youngest was born.

“She couldn’t do it,” Taber said. “And it wasn’t that she didn’t want to do it. She just wasn’t capable.”

Taber’s daughter lived in Tennessee when she got pregnant. She came out to Oregon for help in time to give birth here. The youngest of the four grandchildren spent so much time at Taber’s house that they set up a nursery.

“I kept thinking, you know, ‘Things are going to turn around,’ ” she said.

When they didn’t, and her daughter left the baby in their care, Taber had to switch gears.

She and Fink kept saying, “My gosh, we’re so old,” worried their grandchild would miss out. But they made sure that didn’t happen.

“God bless my husband,” Taber said with her soft Baton Rouge drawl.

“[He] would get up and walk the floor with her, singing,” she paused, “What did he sing … 'Sweet Betsy from Pike,' or whatever the name of that song is,” she laughed.

Taber and her grandchild rode bikes. She and Fink supported her in sports and plays at school. Taber said there were many things she did despite thinking she had never wanted to do them again.

“It’s difficult, but it is rewarding,” she said. “In many ways, I feel like we gave our grandchild a good childhood.”

Every summer, Taber would fly with her granddaughter to Tennessee to make sure she had some connection with her birth mom. But she didn’t really understand the connection, Taber said. And when she finally did, it was difficult. Taber said her granddaughter never said it out loud, but “I know she was thinking, ‘How come she can raise those three kids, but she wouldn’t keep me?’”

They dealt with additional challenges, too. In middle school, her granddaughter wanted to live with her mom in Tennessee. She ended up staying with them for nearly two years, seeing firsthand how they were struggling.

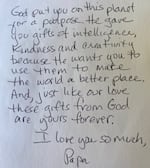

A message from Dennett Taber's late husband, Bill Fink, that he wrote in a copy of the Bible he gave to their grandson when the child was in a mental health care facility. Taber told OPB, "He loved this child so much."

Courtesy of Dennett Taber

During this time, the child came out as transgender male. Taber’s grandchild gave OPB permission to use the pronouns Taber used in explaining their story. Taber also learned their grandchild was having challenges she thinks were separate from the estrangement — he was cutting himself and feeling suicidal. He was later diagnosed with bipolar and schizoaffective disorder.

“Our grandchild’s mental health continued to deteriorate, and my daughter couldn’t [help],” Taber said. “They didn’t have the resources, they didn’t have the money, they didn’t have the insurance.”

The grandchild moved back to Oregon. Taber and Fink dedicated their weekends to visiting him in a mental health facility. Taber attended local PFLAG meetings to understand her grandchild’s gender transition.

She described that time as excruciating and confusing — many people in her and her husband’s lives didn’t understand. They weren’t always sure they were making the right choices.

“What I did decide,” Taber said, “was that I’d rather have a live grandchild of whatever gender than a dead one.”

Starting a support group

At a meeting OPB visited in January, the grandparents support group gathered on the third floor of the Salem YMCA building, the sound of workout equipment occasionally filtering in.

All attendees were women — in keeping with national numbers that show grandmas are more likely to be the caregivers of these children than grandpas. One brought homemade treats to share.

There are a few ground rules: What’s said here stays here. No side talks, no interruptions. No criticism or advice-giving unless requested. Make sure everyone has time to share. Begin and end the meetings on time.

“We want group participants to feel a sense of connection to others who are in similar situations, share collective wisdom, encourage one another, and point each other to resources that are available to assist them,” Geer from the Y explained.

This new group isn’t the only one of its kind — Taber went to a longstanding one offered by NorthWest Senior and Disability Services when raising her grandchild. But Taber and Geer started theirs last year when they noticed more grandparents showing up at preschool and before and after school programs as the primary caregivers. They wanted to help.

They said it’s common for some people to join the group reluctantly, unsure if they’re involved “enough” in their grandchildren’s lives. Taber said anyone taking on a larger role is welcome.

Geer and Taber have structured the group so that experts come in periodically to help share resources — from camps their kids might enjoy to legal advice and tips for handling medical appointments.

But Taber said the general community element among the participants is super important.

Younger people raising their own children, she said, allows for an easier connection with other parents of similar ages. “But when you’re a grandparent raising a grandchild, you’re kind of out on your own.”

‘I’m going to be a better mother this time’

As Taber and Fink raised their grandchild, Taber said she kept telling herself, “I’m going to be a better mother this time.”

“I’m going to do it right. I’m going to have more patience.”

Taber laughed at herself when recalling the notion to OPB. Like any parent or guardian, there’s only so much preparation one can do. But in the end, Taber thinks she did a better job overall.

Today, Taber and her grandson — who still calls her Mama — are very close. He’s 23 now, living in Portland. He got his GED after returning to Oregon and an associate’s degree from Portland Community College. Taber has moved houses, but she keeps his artwork on the walls. They talk daily.

Artwork by Dennett Taber's grandchild is displayed in Taber's home on Jan. 10, 2025, in Salem, Oregon.

Natalie Pate / OPB

She’s closer to her daughter now, too, who’s no longer using substances. After Taber’s other daughter died a year and a half ago, the two of them grew closer. Her daughter always refers to the grandson as Taber’s, but the mother and son have a “reasonable relationship,” Taber said, given the circumstances.

Her advice for others going through this now is to ask for help — whatever form that takes.

“It doesn’t have to necessarily be a group, but you’ve got to have some support,” she said, “whether that means going into counseling or going to church or whatever. You need support and the ability … to talk to people when things get tough.”

Taber said hearing others’ experiences can help you feel understood, maybe even hopeful.

“He’s doing so well now,” Taber said of her grandson, “and that, to me, is worth everything.”

The Grandparents Raising Grandkids support and resource group meets on the first Thursday of every month, October through May, from 10 to 11 a.m. It’s free and open to the public. They meet in the Capital Room on the third floor of the Family YMCA of Marion and Polk Counties in downtown Salem. For more information or questions, contact Valerie Geer at geer@theyonline.org or 971-465-6795.

Note: This story contains a description of suicide. If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988, or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.