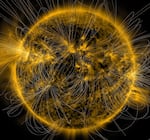

A depiction of the Sun’s magnetic fields is overlaid on an image of the Sun captured in extreme ultraviolet light by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory on March 12, 2016.

Courtesy of NASA/SDO/AIA/LMSAL

If you were one of the lucky people in the Pacific Northwest this year, you might have caught the dazzling show of color in the sky called the aurora borealis. It’s caused when charged particles from the sun hit the Earth’s magnetic field.

It’s relatively rare for the northern lights to be visible this far south, but they were in 2024 because we’re currently in a period of peak solar activity called the solar maximum. It happens about every 11 years.

While solar flares put on an incredible show here on Earth, our understanding of what is actually happening on the sun to trigger these massive explosions into the solar system has been incomplete. But we know a lot more now thanks to new work from an international team, including Vanessa Polito, a researcher at Oregon State University.

Solar flares are caused when the sun’s chaotic magnetic fields run into each other, break apart and reconnect. This generates an enormous amount of energy — picture 10 million volcanoes erupting at once. Part of that energy flies out into space.

Aspects of how these reconnections work had been predicted on paper, but there wasn’t good physical proof because the spots where the fields reconnect are difficult to observe. They slip around incredibly fast — so fast, they could circumnavigate the Earth in about 15 seconds.

Using detailed images of the sun captured by NASA’s IRIS satellite, the researchers were able to identify and track the location where these fields reconnect for the first time, proving the theory.

Understanding solar flares and being able to predict space weather is more critical now than ever. The flares don’t just create beautiful light shows in our sky. They can disable satellites, impact radio communications and our electrical grid and have been linked to increases in heart disease and other health issues.

The research is published in the Nature Astronomy here.

In these All Science Snapshots, “All Science. No Fiction.” creator Jes Burns features the most interesting, wondrous and hopeful science coming out of the Pacific Northwest.

And remember: Science builds on the science that came before. No one study tells the whole story.