Harriet Thompson's slipper was found inside her apartment after police arrived to investigate her death in March, 1998. Investigators theorized blood on the dining room linoleum likely indicated a struggle with her attacker began there before ending in the apartment's living room.

Documents obtained via public records request

No forensic scientist played a larger role in Jesse Johnson’s criminal conviction than Michael Brandon.

In a May 9, 1998 report, Brandon, a forensic tech for the Salem Police Department, wrote that he recovered several items of forensic evidence that connected Jesse Johnson to the murder scene inside Harriet Thompson’s apartment two months prior.

Brandon said he found Johnson’s fingerprint on a vase inside the apartment, as well as a palm print from Johnson on a $5 bill inside a bus pass holder found at the scene.

While Johnson was arrested by Salem Police just days after the March 1998 murder, he did not stand trial until six years later, in March 2004.

Halfway through Johnson’s trial, Brandon discovered another piece of forensic evidence that he said connected Johnson to the scene: Johnson’s fingerprint on a glass bottle of Olde English that police found underneath Thompson’s kitchen sink.

The evidence was circumstantial. But Marion County prosecutors used these items to say Johnson was at Thompson’s place when she was killed.

The fingerprint on the vase proved particularly controversial. On the witness stand, Brandon implied that the red streaks on that vase were blood, even though no police investigator or forensic technician swabbed the streaks. Brandon told the courtroom he had not photographed the vase either. Instead, he made a drawing of the evidence on a fingerprint lift card. That vase was not admitted into Salem Police evidence, and it’s unclear if it still exists.

There is no record of this vase beyond Brandon’s drawing of it. Still, he testified at Johnson’s trial that the fingerprint was collected from between the streaks — which he assumed were blood.

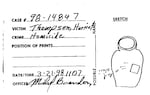

Forensic scientist Michael Brandon composed this fingerprint lift card as he cataloged evidence inside Harriet Thompson's apartment in March 1998. Brandon drew a sketch of a vase inside the home, and testified at Jesse Johnson's trial that Johnson's fingerprint was on the vase near red swipes. Defense attorneys later asked him why he sketched the evidence rather than photograph it.

Documents obtained via court records / OPB

“At that time,” Brandon said on the stand as he referred back to his processing of fingerprints in the Thompson home, “I observed some red stains that appeared to me to be the swiping of blood from fingers and processed that vase.”

“What happened to that vase?” Marion County prosecutor Darin Tweedt asked.

“I have no idea,” Brandon said. “I left it at the scene right on the kitchen counter.”

“Did you do anything in terms of trying to take samples of the red stains you noticed?” Tweedt asked. Brandon said no.

“Why not?” Tweedt continued.

“The Oregon State Police was there and I assumed that they had already done all of the serology at the scene,” Brandon said, using a term for the forensic process of testing biological fluids.

On the stand, Johnson’s defense attorneys questioned Brandon’s decision to sketch the print rather than photograph what he felt was critical evidence.

Documents obtained by OPB indicate that Brandon was focused on linking Johnson to the crime, and at times did go beyond what laboratory science could prove.

In his May 9 report, Brandon said he believed that the print he found inside the wallet was also in blood — a story that requires several leaps in logic. For the palm print on the $5 bill to be evidence of murder, Johnson would have needed to kill Thompson, handled the $5 bill, placed it in a wallet with approximately $30 inside and left the wallet behind at the scene. It’s a story that directly conflicts with prosecutors’ prevailing theory that Johnson killed Thompson to rob her.

Brandon wrote he was certain of the bloody palm print theory because of a strange experiment he conducted.

“I did an experiment using circulated five dollar bills,” he wrote. “One five dollar bill was held tightly in my hand for two minutes and treated with ninhydrin solution. No latent fingerprints were developed on it.” Ninhydrin is a chemical that changes color when it contacts certain amino acids from the human body and is often used to bring forward latent prints.

Brandon continued his test, this time applying cow’s blood to his own palm as he held a $5 bill.

“A clear, bright palm print was developed on this five dollar bill,” he wrote. “This experiment confirmed my belief that the print was in blood.”

That belief proved false.

Salem police sought to confirm Brandon’s assumptions, but on June 12, 1998, a state forensic scientist with the Oregon State Police named Richard Klocko wrote to say their tests for blood on the money came back negative.

Klocko undercut Brandon’s presumptions about the palm print evidence against Johnson. But he too appeared eager to find facts pointing to Johnson as Thompson’s killer. Another document obtained by OPB shows the state forensic scientist writing that he was “hoping” to find evidence supporting theories provided by police and prosecutors that Johnson was the perpetrator.

“Suspect believed to be Johnson. Need to tie him to scene,” Klocko scrawled on an evidence transfer sheet. “Rape & robbery probable motives.”

“Hoping to find suspect blood on items belonging in (apartment) or victim’s blood on his clothing,” Klocko continued.

Police had seized a jacket from Johnson when they arrested him on March 27, 1998. Klocko wrote that it had blood stains on the lining and sleeve. Klocko’s belief was also wrong: Upon further testing, those stains did not prove to be Thompson’s blood, and prosecutors dropped any mention of them at trial.

Klocko did not respond to numerous requests for an interview, and the Oregon State Crime Lab declined an interview request from OPB.

To Janis Puracal, a co-founder of the Forensic Justice Project, the way blood evidence was handled in the Johnson case is a clear sign of how bias can creep into forensic science. Puracal helped uncover many of the implications of bias in Johnson’s case after her own brother was wrongfully accused in a high-profile case in Nicaragua.

“The real question is how can we improve the methodology,” Puracal said in an interview, “(so) we can count on the fact that the method is reliable enough that we’re not getting cognitive bias in there.”

Even as Brandon and Klocko focused heavily on stains they thought may link Johnson to Thompson’s murder, prosecutors have regularly downplayed the significance of other blood evidence at the crime scene that raises questions about Johnson’s conviction.

Forensic scientists working for the Oregon State Police and the Salem Police department collected swabs of blood and other DNA related evidence like this from inside Harriet Thompson's apartment in 1998. Jesse Johnson's defense attorneys have repeatedly requested new DNA testing of some of these swabs because they believe it will prove Johnson's innocence.

Documents obtained via court records

When Salem police detectives first documented blood at the crime scene in 1998, they theorized the killer had likely cleaned up in Thompson’s bathroom. On the sink, they noted a faint spot of blood that had been diluted with water; prosecutors’ theory was that someone had washed their hands in the sink after killing Thompson. If that person had been cut in the fight, a drop of blood mixed with water could have fallen on the sink.

DNA tests of that spot, which later became known as “spot 15” due to how it was logged into evidence, showed it did not come from Thompson or Johnson, meaning someone else had bled at the crime scene.

Today, Johnson’s defense attorneys continue to push for additional DNA testing of spot 15 because they believe that is likely a person involved in Thompson’s death. On Aug. 13, attorney Richard Wolf filed a motion in Marion County Circuit Court asking a judge to either mandate additional testing of spot 15 or fully acquit Johnson.

A Salem police detective points to a faint spot of blood on the bathroom sink inside Harriet Thompson's apartment in March 1998. DNA tests would later reveal that this blood did not belong to Thompson or Jesse Johnson, the man who was eventually convicted of her murder.

Documents obtained via court records

“If the prosecution truly has no intention whatsoever of ever proceeding with this case again in the future, then the dismissal should be changed to one WITH prejudice and a judgment of acquittal should be entered,” Wolf wrote, meaning Johnson would be considered fully innocent. As the case stands currently, Marion County prosecutors have preserved their right to bring future charges against Johnson if they chose.

Though the futures of Johnson’s case and the DNA testing remain in legal limbo, Puracal said cases like Johnson’s highlight why the state’s crime lab should be separated from the Oregon State Police, making it more independent and less directly aligned with outcomes prosecutors would like to see.

Listen to all episodes of the “Hush” podcast here.