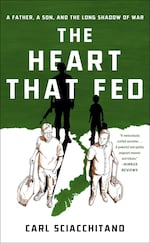

Portland author Carl Sciacchitano's debut graphic novel, "The Heart That Fed," focuses on his father's experience in the Vietnam War and the decades that have followed.

Courtesy Simon & Schuster

Portland author Carl Sciacchitano’s debut graphic novel, “The Heart That Fed,” focuses on his father’s experience in the Vietnam War and the decades that have followed. It also follows Sciacchitano as he watches his father struggle with the psychological effects of the war. The book explores their relationship and the many nuanced ways that PTSD can affect families and communities.

Sciacchitano and his father David join us to talk more about the book and what it was like to travel back to Vietnam together.

The following transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer:

Dave Miller: From the Gert Boyle Studio at OPB, this is Think Out Loud. I’m Dave Miller. The Portland writer and illustrator Carl Sciacchitano has created comics for MonkeyBrain, Archie and IDW. He illustrated the graphic novel, “The Army of Doctor Moreau” with fellow Portlander David Walker. Now, he has released his own graphic memoir; it’s called “The Heart That Fed: A Father, a Son, and the Long Shadow of War.” The father in the title is his father David Sciacchitano, a Vietnam veteran who came home changed by PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] and the horrors of war. The book goes back and forth in time from the battlefield, to Carl’s childhood, to a trip they took together to Vietnam four years ago. It is a sensitive portrayal of trauma, healing and family.

Carl and David Sciacchitano join me now. It’s great to have both of you on Think Out Loud.

Carl Sciacchitano: Thank you so much.

David Sciacchitano: It’s great to be here.

Miller: Carl, first. You’ve written – this was in an essay in the New York Times recently – that you were “born into an angry world.” What do you mean by that?

C. Sciacchitano: Well, it’s pretty literal. But I described it once as sort of like showing up to a party late, and there’s all these dynamics at play, and you aren’t quite aware of what’s going on, but you learn to adjust and figure things out. When I arrived, my parents divorce was starting up. My brother was upset at the changes in his family all of a sudden – he had been an only child for six years. Of course, my mother was upset about that experience. And my father, too, was often angry. It was much longer until I realized what the source of a lot of that anger really was, which was PTSD and his experiences during the war.

That was oftentimes the dynamic in our household, and it was something that when you grow up in an experience like that, you just take it for granted in the sense that you sort of innately understand how people react to certain situations. And you do your best to work around and avoid those triggers that you realize exist in the family and home.

Miller: Were you always walking on eggshells?

C. Sciacchitano: I wouldn’t say it was always walking on eggshells. I think that’s a little too strong. But I just learned to understand pretty quickly what might make someone angry and what wouldn’t. And I think you learn – maybe when you’re the youngest child, too, I don’t know – but just to navigate that, and to kind of placate people, and to try and just maintain peace, and to navigate it for yourself, and to make decisions that work best for everyone and for yourself. Yeah.

Miller: You said it took a while before you connected that to your father’s history. When did that start to happen, to connect his extreme reactions that you saw or experienced growing up to his time in the war?

C. Sciacchitano: It was quite a bit longer. I knew about my father’s experiences during the war in the sense that he was a veteran, that he was in the Air Force. When I was young, I grew up hearing all these different stories about things, but they were a censored, I think, version of a lot of events, or he would pick the ones that were most suitable for a child of whatever age I was at the time. So when I was really little, I would hear stories about screwing up an exercise in basic training, something sort of innocuous.

As I got older, as our relationship grew and changed, as I learned more about the war, as my father’s experiences as a veteran changed post-9/11, as there was a greater acceptance of the veteran experience in this country … there was really a sea change in that time. So he began to open up more, I began to learn more. There was more of a conversation between us, more of a dialogue. But in terms of really connecting – I mean, I didn’t really know what PTSD was for a long time. He certainly wouldn’t acknowledge that it was something that afflicted him for a very long time. So, in terms of really identifying that concretely and connecting it to the war and all of that, that was not until probably I was really in college.

Miller: David, let’s go back almost 60 years. You dropped out of college after your freshman year and then took some odd jobs as a welder, as a technician at an animal hospital. [Laughing] There’s a panel in the book with, I think it’s feces …

D. Sciacchitano: The technician in the animal hospital was washing animal cages. They called it a “technician,” but it was just washing poop out of cages.

Miller: It seems like poop is being thrown at you by an ape in that picture. This was in 1965, when the war and the draft were both ramping up. What options did you have as a college dropout?

D. Sciacchitano: What do you mean – to avoid going in the service?

Miller: Well, first of all, I mean, was there any way you could at that point have avoided going into the service?

D. Sciacchitano: If I’d gone back to school. I mean, the exemptions for the draft were pretty clear-cut. Everybody knew how to stay away from it. If you were in school, for that period of time when you were in school, you could get exemptions if you asked for them – you had to apply. And then once your exemptions were up, you were eligible for the draft. That’s an old system. It wasn’t just for the Vietnam era. And then, you had other ways of getting out. I knew people I went to school with who had a doctor who was friendly write a letter. They were unscrupulous ways of getting out.

Miller: You could develop bone spurs.

D. Sciacchitano: I didn’t have … those were not available to me.

Miller: But you theoretically could have gone back to school. Instead, you chose to enlist in the Air Force. Why?

D. Sciacchitano: Well, the problem I had was I was kind of aimless in those years and immature in a lot of ways, but also aimless. I didn’t know where I wanted to go or what I wanted to do. And my first year of college was enjoyable in some ways, but I felt at the end of it, that I’d wasted a whole year and my focus hadn’t increased on anything. I still didn’t know what I wanted to do. And I don’t know if any other people have ever felt this way, but I had this kind of fear that I’d do three more years – and they go by quickly, those years in college – and I’d have a degree meaning nothing, and I wouldn’t know what I wanted to do. I wouldn’t know what kind of job I was gonna get. I had no career in mind. I wasn’t ready to go back and the draft was looming. I mean, it was one or the other. So I ended up going into the service; I just wasn’t ready to go back to college.

Miller: I wonder if you could read us a letter that’s included in this book. There are a couple letters to your sister Sandra that your son included in the book after he found out, years into his own life, that these existed. And this is a letter that you wrote to her when things were about to get serious.

D. Sciacchitano: This was after I was already in the service. I was at Charleston Air Force Base, and I wrote – here’s the letter, it’s: “Dear Sandra, I’ve got some news. I’m going to Da Nang, Vietnam this November, PCS [Permanent Change of Station] for one year. I could get a cancellation, but I don’t think so. Now don’t get all excited and worried. In the first place, I volunteered for it, so I’m not getting anything I didn’t ask for. Da Nang is supposed to be a pretty nice base, but I’ll let you know when I get there. I doubt if it is very dangerous; however, I expect the VC [Viet Cong] to clear out as soon as they hear I’m in the area. Your loving brother, Dave, who’s really just as chicken as everybody else but is afraid to show it.”

Miller: You were an airline mechanic, away, theoretically, from the front lines. And here you are telling your sister that you doubted it was going to be very dangerous for you. Did you believe that at the time, or were you just trying to make her feel better to assuage potential concerns?

D. Sciacchitano: Actually, I don’t think I’ve ever talked about this, but maybe I have with Carl. When we went over, we had like minimal information. The military is really kind of strange. Doesn’t matter what branch you’re in, you get trained pretty well for the specific things you’ve got to do, but there are a lot of other things you just have to pick up. And you’re expected to be just dropped into a situation and work, get to work and get your job done – doesn’t matter what it is. You could be a machine gun or you could be a cook. Whatever it is you’re expected to be picked up, dropped in and do it. That’s the only way it can work; that can’t work any other way.

We had minimal briefing on what was gonna happen to us when we went to Vietnam. I did not understand that the squadron I was going to, the main part of it, was not actually at Da Nang Air Force Base. That was my assignment, my permanent station, as they call it. But most of the squadron was actually out in the field. They were out in forward locations because the squadron was divided up into smaller groups, and the groups were attached to different military organizations, infantry organizations. So when I wrote that letter, I thought I’d be at Da Nang Air Force Base for a year, and it turned out I was at Da Nang Air Force Base for five months. Then I extended for six months and I was out in what we called the “up country” for about 13 months. But I didn’t know that at the time. I was not aware of it.

Miller: Can you describe what the Tet Offensive was like where you were, and what it was like for you?

D. Sciacchitano: You mean that particular day, at the moment?

Miller: Yeah.

D. Sciacchitano: Well, we had a normal day. Our normal day was pretty long and tiresome, and it was hot. I just remember it was a very hot day. We worked really from dawn to dusk, sometimes at night also. So we came in late that day, barely got into the … in this compound where we were, we were with some advisors. We were the only Air Force people there. It was mostly US Army people, some Marines, Navy, some Australians. And we got in there for chow. And just as we were finishing up, one of our officers, an army officer, came in and called everybody out and divided everybody up into groups, four groups. [He] said we were going to be on the bunkers all night. We all knew our positions. We all had positions to take up when there was any kind of problem. So, that wasn’t all that strange, except that we’d never been called out that way and put on early. Normally, there would be a mortar attack all of a sudden at night, and you’d run out to your bunker, or you wouldn’t run out to the bunker or whatever, and it would be over in a few minutes. In this case, it was a little bit different.

So my reaction was – I just was set up, I was so tired. I was really tired, and all I wanted to do was go to bed, and a lot of these things were false alarms. When we’d be put out on the bunkers, nothing would happen. And then when we weren’t put on the bunkers, something would happen. You know, that sort of thing. [Laughs] The predictions were never right. So I thought it was just another one of those nights. So that was it, and I was put on my position.

I’ll mention one other thing here. I don’t want to talk too much on this, but it’s a good example of how the Air Force didn’t really prepare us because we had absolutely minimal weapons training, with two days of weapons training in the Air Force. So when we were up-country, we were in a situation where we really needed to know a lot more about our weapons than we did from Air Force training. So a lot of that, we had to pick up ourselves. In fact, almost all of it, we had to pick up ourselves.

At any rate, they divided us up, and we were put on separate bunkers, and then stayed on the bunkers trying to stay awake all night. At a certain point – trying to think of what it was – in the early morning, the officer that I mentioned came by, and he said that Huế, which is a big city south of Quảng Trị, had been overrun. And that sent chills up my spine. Huế was a big city, and I’d never heard of such a thing in my life. He said, Huế has been overrun, which means it’s occupied by the communists. So that kind of woke me up. That was the situation when, right before we got attacked, we were really heightened alert all of a sudden because the reality was, it wasn’t just another night and something really was gonna happen.

Miller: Carl, as you said, you had heard first sort of censored, maybe sanitized versions of your father’s stories from an early age that got, I think, progressively fuller and more detailed, more age appropriate as you got older. How did you decide that you actually wanted to turn his life, his experiences, into a graphic novel?

C. Sciacchitano: Well, it started initially because – in the story that you just heard, was a good example of it – I knew my father had this really dramatic career in Vietnam. He also, in addition to being there during the Tet Offensive, was back as a State Department Officer later in the Foreign Service, and was there during the evacuation in 1975. So he saw the war from so many different vantage points over this large span of time that I think is unique, fascinating, dynamic and all that. So that was kind of the germ of it, telling that story.

Miller: Am I right, that he would say to you, “Yeah, but how interesting is my story?”

C. Sciacchitano: Well, when I first talked to him about doing the book, of course, I wanted his permission and involvement. And that was really vital to the book being, I think, compelling at all – his involvement in it and his participation with me in creating it. But yeah, his only reservation was, “Why would anyone want to read a book about me?” There was never any, “Don’t do this,” or “Don’t say that,” or, “I’d rather you don’t include anything.” There was nothing like that except for, “Are you sure anyone’s going to want to read this book about an Air Force mechanic?”

Miller: What was your response?

C. Sciacchitano: I just thought he was wrong. I mean, I just didn’t think he could see outside of himself, but I felt pretty strongly that people would find it interesting. I think the ironic part of that, though, is that similarly, when I realized that people were really grabbing on to the part of the story that I was in, that my involvement, that my relationship with my dad was a hook for people that was really interesting to them, I had kind of the same reaction. I was thinking, “Why am I going to be in this thing? No one wants to hear about me. They want to hear about my dad.”

Miller: So at first, this wasn’t going to be a kind of a multigenerational tale; this was going to be about just your father’s experiences?

C. Sciacchitano: Yeah, in the very earliest iterations of it in my head, but this is going back 12 years or something. Yeah, I thought it would just be telling my dad’s story. Just this kid who ends up in Vietnam, is thrown into these impossible situations, and gets out of it, and survives and stuff. I realized, as I was working on it though, that – especially because I didn’t really want to do something that was heavily sort of narration driven – I wanted you to feel like a fly on the wall as a reader. And, I felt like in order to do that then, there had to be someone that was sort of bouncing these things off of and that my father was growing alongside of during the story, right? So you could see how the war affected him afterwards. And so sort of me as a character, that’s how I ended up in the book. As early people read it early on, that was clearly a part of the book that really resonated with readers. And I realized that it had to be kind of a spine of the story alongside my father’s story in Vietnam.

Miller: David, there’s another letter that your son included in the book that’s pretty harrowing. You describe to your sister seeing Vietnamese prisoners of war left to die in the sun by your fellow servicemen as other people gathered around to watch. You described it to her as puzzling and disturbing, and you asked her why it could happen. You asked her to maybe ask some of her professors for history, or context, or explanation.

I’m curious how you remember – and this goes back almost 50 years now – grappling with the atrocities of war while you were there?

D. Sciacchitano: Yeah, let me clarify that. They were not American troops; they were Vietnamese troops. I was not around very many Americans, actually. We were the only Americans in the area. But we were attached to a Vietnamese regiment, a South Vietnamese regiment, so it was members of one of the battalions of that regiment had come back from an operation, and they had a number of prisoners they brought back. And they had two badly wounded prisoners.

As I was coming up the road walking – I can’t remember why I was on foot, because I usually wasn’t on foot – and some South Vietnamese soldiers were dragging two guys by their feet from an area across this landing strip where we worked on one side, and they dragged them across to the other and dropped them. One fellow just looks like – I mean, I don’t want to describe it; he was pretty bad looking. And then, the other fellow was not as bad, but one was dying and the other one was not in good shape. And nobody did anything for him. I mean, they just dragged them over there. It must have been 105 degrees out, and they just left them there, and they were chatting with each other. Not necessarily even paying any attention to these two fellows other than the fact of having physically dragged him over.

And I felt like I needed to do something. I felt helpless, because I thought, “Gee, I gotta do something.” I said, “I gotta do something,” and I didn’t know what I could do. I didn’t know what … it was like, I’m sitting in my culture and they’re their culture. How do I bridge this gap? How do I cut across that? Get these guys a drink of water, or put some shade over their head, or something. And I just was frozen. I couldn’t do a thing. That’s really what bothered me right there. I was unable to help these two guys ...

Miller: I was curious, Carl, when you would hear stories like that or maybe read about some of these things in letters, how did you decide what to include of these horrors in the book? And how to portray them, to illustrate them, to describe them?

C. Sciacchitano: Well, I continually discover and hear new things about my father’s experiences. As you just mentioned, a lot of this is 50 years old, some of it. And so he uncovers new things in his own mind. There’s really an excavation that took place, I think during this. I found out about these letters that existed that my aunt had kept for all these years. I didn’t know these existed until after I started making, putting the book together. I read that letter in question, and that one in particular just felt so compelling and something that I just felt needed to be in the book – the honest inner thoughts of a kid, really, who’s looking at something they just can’t wrap their head around and is trying desperately to figure that out.

Miller: A kid who’s way younger than you are right now.

C. Sciacchitano: Oh, yeah. Right. And that’s an interesting point I think we all go through with our parents, when you realize you’re the same age as they were when they had kids or whatever, right? But I think, particularly looking back at my dad’s experiences and thinking, “Gosh, I don’t know how I would be able to deal with this when I was in my early twenties.” You think about what you were doing in college, or goofing off with friends, or something, and thinking about what he was doing at the same age is hard to wrap your head around.

So there are still things that I found out since, that didn’t make it into the book because we just keep talking to people. And things keep coming in his own head about his recollections during the war. There wasn’t a lot that I really left out, I don’t think, but that in particular was something that I just felt was – I’m not even sure really how to describe it, as he has trouble doing it, too – something that was just such an important, I thought, encapsulation of what that experience is like for someone to be thrown into a situation that is so horrifying, and so difficult to understand and grapple with. But you’re just kind of doing your best, and also the way that for other people around him, it was kind of just another day. It was just a matter of fact, this is one other day and then a bunch of other things happening. And for those other Vietnamese people, it wasn’t really out of the ordinary at all.

Miller: David, as Carl mentioned, you had the, if not unique, then I think relatively unusual experience of first serving in the Air Force in the late 1960s. And then, when that service was done, you went to college, spent some time in grad school, then were in the foreign service and went back to Vietnam not that long before the fall of Saigon. That was not your plan, as we learned in the graphic memoir. You didn’t want to go back there, but that’s where the federal government said they wanted you. What was it like to be back for those months?

D. Sciacchitano: Well, I not only didn’t want to go back, it was the last place on earth I wanted to see. I tried to get out of it. I was really faced at the end with either resigning or going. It was an 18-month assignment. So I said, “OK, I’ll try it and see if I can stand it and if I can’t stand it, I’ll quit.” But it didn’t last long. I got there at the end of January and things started falling apart in March. So it was pretty clear to me that I wasn’t gonna have an 18-month tour after all, but I was ready for an 18-month tour to see if I could make it through that.

I didn’t wanna go back. I didn’t want to see it again. And I think that’s pretty typical. If you ask most Vietnam veterans, who haven’t gone back for one reason or another, if they want to go back, most of them will say no. Because you’re going back to too many difficult things, feelings, emotional things. But I went and it was tough in a different way. Just to watch the people lose their country, to lose everything they had, just all collapse, it’s hard to describe. It’s sort of beyond tragic. It’s too vast an event when you’re in the middle of it to describe that way.

It wasn’t pleasant, but I kind of went through it almost sleepwalking, ‘cause I got busy every day – busier and busier as the end approached. I was charged with trying to get American citizens out, or children of American citizens. We didn’t have all that many, but it was hard finding them, hard getting them out, hard getting the paperwork done. The evacuation itself wasn’t very well-planned on the part of the Embassy. I was down in the Delta, by the way. I wasn’t at the Embassy; I was at a consulate general in the Delta, south of Saigon. So there are a lot of difficulties involved. In a way, I was also glad it was ending. I mean, I had this mixed feeling, because I was saying, “Gee, I don’t have to stay here after the whole 18 months.” And at the same time, I felt guilty about that, because the reason I’m not staying is because these people are losing everything they had. They’re losing their life’s work and, in many cases, losing their lives.

But plus, there was a little bit of violence also at the end there, which was similar to what I … we had a rocket attack on the city, we were shelled, we had a big artillery bombardment we went through. So that was kind of like being back in the Air Force really, when I was in the service. In fact, the worst artillery barrage I ever went through was then. It was by far the heaviest artillery barrage, even heavier than the Tet Offensive. So it was, I don’t know, it was dramatic, emotional, it was all these crazy emotions mixed up again.

And after that, I ended up working with refugees. I ended up on Guam working for a month with refugees on Guam, and I was working with refugees out of Washington DC for a while. So I ended up being immersed in Vietnam all over again, completely outside my own will. I had no free will involved in this at all; it’s just the way events went. It’s like the war grabbed me at one point, and I was never able to get away from it. Does that make sense?

Miller: It does. I want to skip forward a little bit in time once again and bring Carl back here. I wonder if you could tell us your experience of something that you write about in the book, where you would come home from college, and you found a father who it seems like was in the middle of a lot of major changes. What were you seeing? What was changing?

C. Sciacchitano: Yeah. I mean, outwardly it was just a much greater willingness to tell people that he was a Vietnam veteran. That was never a secret in the family. You hear so much from family members, or especially sons and daughters of Vietnam veterans, that their parent just never talked about it. And that wasn’t really the case. My dad told me about a lot of things, told my brother and the rest of the family about a lot of things. But, outwardly, it was very surprising to see him wearing, all of a sudden, hats that had “Vietnam Veteran” on the front, or have bumper stickers on the car, or he had a vanity plate made up that said “MACV Team 4.” And he was more involved in veterans groups, and things like that.

So, yeah, it was a surprising but welcome change. I always felt that there was so much there that he deserved to be proud of, for what he had done, and for what he had survived. And I was happy to see him not shrinking away from that anymore.

Miller: David, this is about 30 years – if my math is correct – after you’d gotten back from your tour of duty. Why was it that it was at that point that you sought out care from the VA, hearing aids, counseling, and that you were much more willing to publicly show that you were a Vietnam veteran?

D. Sciacchitano: Oh, a lot of that’s coincidental with time. I’m not sure. I mean, from my point of view, it seemed coincidental. Who knows, with life, what is and what isn’t. But, I was having emotional issues – personal issues, I should say. I wasn’t able to sort out problems with my marriage, second marriage. So I went to the VA to see if I could get some counseling.

Actually, it’s kind of a funny story about why I went to get my hearing tested, but I did. I’d gotten it tested in the ‘80s, but they were so unfriendly at the VA. [They] made it clear they didn’t want to have anything to do with Vietnam veterans. I never went back. I needed hearing aids from the time I left Vietnam. But when I went to the VA, the VA was hostile to Vietnam veterans. So, I never went back there. And then I did and found that there was a much friendlier place, much more welcoming. So I got my hearing aids because I needed them; I should have gotten them earlier.

I ended up in PTSD clinics all of a sudden because I did an interview with some kid who was an intern. He said, “Just a minute,” after a minute of talking to me – it was kind of funny [laughs] – that he called, he went out, and he came back with a psychiatrist, and the psychiatrist looked at me, and he said, “It’s about time.” [Laughs] I’m laughing about it now, but this guy looks so serious. He gave me this look. I guess my face must have shown some kind of a bad emotion. He said, “It’s about time.” And that dragged me into it. It was like, I got it out of my system or something because of that little visit, looking for some kind of counseling or because of personal problems. So that’s how I ended up getting into PTSD programs ...

Miller: Carl, I’m curious what you hear in that? I mean, to have a doctor say, “It’s about time.” I imagine that, as a son, you were saying the same thing?

C. Sciacchitano: I don’t know if that’s true, actually. I think because everything’s filtered through a lot of your parents’ experiences, I think, in these situations, right? So even though by that point I knew about PTSD, I’d heard about it, when I brought it up with my dad prior to that, his answer was no, he didn’t have it. The people who had it had problems going in, they had some kind of issue initially. I look now, back on that, and I think in a lot of ways it’s pretty tragic because I don’t think he was making that up. I think he was telling me something that he thought was true but had to sort of stop short of explaining it further.

Miller: And something you had come to believe as well?

C. Sciacchitano: Honestly, my understanding of it, I think, really only opened up once he did. I don’t think I still knew enough about it to really understand. And also, we grew up in a Sicilian family, there’s different ways that things like that behavior can be kind of explained away –“Oh, you’re just an emotional person. We all talk loudly. It’s just that side of you.” There’s a lot of ways that that kind of behavior gets couched in other terms or something. So I think it really took my dad doing that work for me to be able to see it as clearly as he did.

Miller: David, I’m startled by something that Carl said earlier, that when he approached you and said he wanted to do this, it seems like your only concern was, “Well, I’m not sure that people are going to be interested.” But you gave him your blessing and you said, “Yes, you can do this.” And also, if I understand correctly, you didn’t say, “Don’t include this” or “Be careful about this.” He had free rein to write in detail about your life, about what you’d experience, and also your anger, your volatility, some scary things you had done.

Where do you think that trust came from? That you said, “Yes, Carl, you can do whatever you want”?

D. Sciacchitano: You know, that’s a good question. I never thought of it, but you’re right; I guess the trust level, that’s part of it. My main feeling was that he was my son [and] I wanted to be supportive. I was always supportive of his artwork. The only thing I ever worried about when he decided to really focus on art was that, when he was in college, he take a double major so he could teach history if the art didn’t work out, something like that. But I was very proud of the way he worked at his art – he was really focused on it since he was very young – and he worked very, very hard at it. There’s some stuff I think he did when he was 15, 16, that’s terrific, and he hates it. So he thinks it’s just terrible; I think it’s wonderful. And it’s not just because I’m a dad. I think he’s just a kind of a perfectionist. So, my view was, “I’m his dad. I’ve got to be supportive.” And he was very sensitive, he was very sensitive to me, and I could feel that he was sensitive. And I shouldn’t say that helped, but anytime that somebody is like that, it gives you a certain degree of confidence.

Miller: Because you felt that by showing that he had concerns, that he was clearly taking your feelings into account, by even the way he was asking questions.

D. Sciacchitano: Very much so, very much so. It was very clear when he was talking to me … in the beginning, he’s asking me sort of, “What can I talk about? What shouldn’t I talk about?” And I basically said, “You do what you want, write what you want. Don’t worry about my feelings.” I really said it just that way: “Don’t worry about my feelings. I’ll deal with those. You do the book the way you want to.” And we talked about certain things, but I didn’t object to anything. I didn’t ask for changes.

Some of it’s embarrassing. I was actually reading through some stuff today. Some of it’s hard for me to read. It’s not easy for me to read the book – I’ll say that, even though I’ve read it several times. It’s not easy to look at yourself in the mirror that way. But my main view was, that’s too bad; that’s my problem. I wanted him to write the book the way he wanted to write the book.

Miller: Carl, it’s high praise to have the subject of your book talk about it that way, to see it as, in a sense, looking in a mirror.

C. Sciacchitano: Yeah. And I think being able to have that really open honest conversation. I mean, my father and I spent just countless hours, over many years, talking about all facets of his life, and the Vietnam experience, and how things connected to that. And I always wanted to make sure that what I was putting in the book connected back to his experience in Vietnam. I didn’t want it to just be an airing of grievances, or this unhappy memory about your dad, or your parent, or whatever, your life growing up, your childhood. So I think being able to have those conversations, and I would sit down and say, “OK, I remember this happening. When you reacted like this, do you think that was because of a PTSD response, or was it just something else? Was it just –” Because, it’s not always a trauma response; it’s not always PTSD. There’s other issues in dynamics in families and those kinds of things. So I really wanted to make sure that that felt truthful, and connected back to the core theme and experience of the book.

Miller: We just have about a minute left. Carl, you ended up arranging a trip to Vietnam for the both of you right before COVID hit. Your first trip ever there. Your father’s first since the fall of Saigon. Why was it important to go?

C. Sciacchitano: I just felt that it was really critical for me to be able to see, and hear, and taste, and everything [that] my father had – to whatever extent I could. Obviously, the country had changed quite a bit. I mean, there was that part for the book, and I think also just as a father and son experience to go back there together, and to have another kind of, I don’t know, way to share the experience, in a way – for me to be able to reach out and sort of touch the edges of something that he experienced.

Miller: Carl and David Sciacchitano, thank you very much.

C. Sciacchitano: Thank you.

D. Sciacchitano: Thank you.

Miller: Carl Sciacchitano is a Portland-based writer and illustrator. His debut graphic memoir is called “The Heart That Fed: A Father, a Son, and the Long Shadow of War.” We were also joined by his father, David Sciacchitano.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.