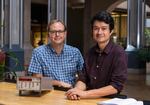

Professors Christopher Hendon, right, and Josef Dufek are brewing coffee at The Oregon Coffee Laboratory in Willamette Hall on the University of Oregon campus, Eugene, Ore., on Nov. 13, 2023.

Courtesy of the University of Oregon

The Pacific Northwest has been a hub for coffee culture for nearly a century. But it may surprise you to know that we have scientists here whose entire field of study is the chemistry of coffee. Christopher Hendon is an associate professor at the University of Oregon who has the appropriate nickname of “Dr. Coffee.” He and a team of volcanologists on campus have found a way to up your coffee game: by adding just a little spray of water before grinding your beans. His team’s study on reducing static charge in coffee is featured in the science journal, Matter.

OPB’s “All Things Considered” host Crystal Ligori spoke with Hendon about all things coffee. Listen in, or read an edited transcript of their conversation below.

The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Crystal Ligori: So I know the research your team has done centered around this idea of adding just a little bit of water to the coffee beans before they’re ground. I understand some coffee pros are already doing that — but no one actually studied the why behind it until now?

Christopher Hendon: Yeah, that’s right. Actually, this is a really nice example of academic research being inspired by some industrial know-how. So when you grind coffee, the process creates a tremendous amount of static electricity. And this has been a known problem in the coffee industry, and other industries for that matter, for a very long time. The practitioners that — basically baristas if you like — have been trying to mitigate this charging. About maybe 10 years ago, the idea was originally posited that maybe one or two drops of water on the whole beans would seemingly reduce the charge. Perhaps it was never charging in the first place in the grinder, or perhaps the water was just creating a surface layer on the coffee grounds themselves. They didn’t really know, but the observation generally was that you were seeing fewer charged particles so there was less mess.

So we were inspired by this because that is obviously a nice scientific example of a macroscopic observable — like less mess on my counter. But then something happening on the microscopic level, like for example, maybe no charges were ever formed. And we wonder why that is, and what could possibly be giving rise to that.

Ligori: What does your research mean for coffee drinkers when we’re figuring out what kind of beans to buy? Because I know that different roasts have a different amount of moisture in them already.

Hendon: Generally coffee starts out somewhere around 10% internal moisture, and then you roast the coffee, turning it brown and eventually maybe even black. And as you roast it darker and darker, you’re driving out more and more water. So generally we find that for dark roast coffees, they’re going to charge a lot more, and a lot more negative; whereas light roast coffees actually do charge as well, but sometimes they even charge positively. So this is a pretty interesting phenomenon because it’s very rare to find a material that can not only charge a lot, but also change its polarity from positive to negative, depending on its chemical composition.

So generally the idea here is that if you’re going to add a little bit of water, you’re going to see the greatest impact in charge reduction for darker roast coffees because those are the ones that have the most charge. But you’ll also still see the impact for light roast coffees as well, of course, because we’ve all experienced that with the light roast, you grind them and they go everywhere too.

A team of chemists and volcanologists at the University of Oregon are researching how moisture affects the buildup of static charge when grinding coffee. It turns out, adding a spritz of water to the beans before grinding reduces static charge, producing a better cup of coffee.

Courtesy of the University of Oregon

Ligori: Yes, I definitely have coffee chaff like all over my countertop after I grind. I do have a little bit of a background in coffee myself, but it has been a minute since I was pulling shots at a cafe. So what are the real world applications of the study, both for a home setting, but also in a cafe?

Hendon: So I’ll start with the home setting. I mean, fundamentally the biggest advance here for the average user is going to be that the addition of a single drop of water, or as little as a single drop of water, is going to make a marked difference in the amount of static dust that’s generated while grinding. So this means that when you grind your beans, you’re not going to see that stuff stick to the surface of the grinder and cover your counter and so forth. So fundamentally, it’s just cleaner.

In the industrial setting, it’s a little more complicated. Because if you’re thinking about the brew situation that would give rise to the biggest difference — in having the particles be freely flowing from one another versus being clumped — that’s an espresso. But in an espresso format, in a cafe, they’re using grinders that have to go through a tremendous amount of coffee during a busy period in the morning, for example. So right now, there’s actually not a technology on the market that is going to introduce water to those beans as you’re grinding in a busy cafe.

It’s not something that you’re going to see in most cafes in most environments for quite some time. But the cafes themselves are the place that stand to benefit the most, because if you can extract more from your coffee, that leads to a direct monetary savings for the industry.

A team at the University of Oregon is researching how a small amount of water on coffee beans before grinding can reduce static charge and improve extraction. Chemist Christopher Hendon (second from right) and volcanologists Joshua Méndez Harper (far left) and Josef Dufek (second from left) published their research in the journal Matter in December 2023.

Courtesy of the University of Oregon

Ligori: You’re a chemist and ‘Dr. Coffee’ by profession — but for this study you also teamed up with volcanologists on the UO campus. Volcanoes aren’t exactly what I immediately think of when I think of coffee. So can you tell me more about how that science overlaps?

Hendon: This is a great example of a fruitful collaboration. I built the coffee lab in a public space on campus — and I encourage the listeners, by the way, to come and visit us because that’s part of our science outreach program. And in one of our outreach activities, the volcanologists were there and were observing this static charge being generated during grinding, and considered this in the context of their work. Now basically when a volcano erupts, it creates a plume of ash that gets ejected into the atmosphere. Sometimes the ash is so charged and staticky that you see lightning discharges above volcanoes. And actually the amount of charge and these discharge events are very useful for studying the inside of the volcanic plume, where of course you can’t fly a helicopter or send a drone because you’re in the middle of a volcano. So instead, you can use the charge to learn something about the topology of the volcano. They basically simulate eruptions in the laboratory with a small plume of dust that gets ejected into a box, and they study the charging.

So we had the technology on campus already, and certainly weren’t the ones to invent it. And instead we just repackaged it and basically placed that technology underneath the grinder. We’re really just using expertise from the volcanologists, that I had no idea was even something that people studied. But at the same time, they also had no idea that charging and coffee was something that mattered on the industrial scale to the coffee industry. So really this was a really nice example of having this open platform for us to meet each other, talk about pertinent problems and hopefully do some really excellent science.

Volcanologists Josef Dufek, left, and Joshua Méndez Harper are part of the team researching how to reduce static charge when grinding coffee. They've helped adopt technology used in their research to study coffee a The Oregon Coffee Laboratory on campus in Eugene, Ore.

Courtesy of the University of Oregon

Ligori: I know that you’ve shaped your career around coffee, so I am curious — what is your favorite way to drink coffee?

Hendon: Well in the morning when I get up, I prepare one cup for myself and one for my wife. I really enjoy that period of time, because then I go off to work and I don’t see her for the whole day, so that’s certainly my favorite way to do it, to just pour over coffee in the morning.

But you have to remember, I work in a coffee laboratory as well. So every day I’m surrounded by students, excellent undergraduates and graduate students that are working with coffee, and they’re always producing extracts that are worthy of tasting. So my favorite one is the one that makes the students really excited — they have that ‘Aha’ moment, and they realize this is why they’re interested in this topic, because there’s flavors and sort of novel science that they’re unpacking. But they’re able to taste the difference in their science, and that’s a really unusual but fun opportunity that sets coffee science apart from typical chemistry.