On the morning of Friday, Oct. 3, 1873, as many as 2,000 spectators gathered in the remote military outpost of Fort Klamath in rural Southern Oregon for the execution of Modoc war leaders. It marked the end of the Modoc War of 1872 to 1873.

The war nearly destroyed an Indigenous culture dating back thousands of years, but the Modoc people have proved resilient.

Today, those events 150 years ago remain an important part of the region’s history. Ongoing research provides new insights, helping descendants both remember the past and heal long held wounds.

“— Robert Burkybile, Modoc Nation of Oklahoma Chief, April 2023We are here to gather and remember what our Modoc ancestors endured 150 years ago.”

Remembering the sesquicentennial of the Modoc War

Over the last year, groups throughout the Klamath Basin have held a series of remembrance events, marking the 150th anniversary of the Modoc War and its aftermath.

The activities included lectures, exhibits, tours of battle sites, film screenings and ceremonies to honor the Modoc people and their history.

“This is such a complex and sometimes such a sensitive subject, we want to make sure that we recognize that there’s different perspectives on just about every aspect of the Modoc War,” said Todd Kepple of the Klamath County Museum.

Origins of the conflict

After years of conflicts with encroaching white settlers, in 1864, Indigenous tribes in Southern Oregon and Northern California signed a treaty with the United States government. The treaty merged the Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin people into one entity as the Klamath Tribe, and placed them all together on the Klamath Reservation.

In this image circa 1870, Modoc clan leader Kintpuash, also known as Captain Jack, poses in a photographer's studio in Northern California.

Courtesy of Legends of America

The arrangement didn’t work for everyone.

The Modoc leader Kintpuash, more commonly known as Captain Jack, repeatedly asked the government to create a separate reservation for his people on a small portion of their traditional homelands in Northern California. The area amounted to roughly six square miles of lava flows on otherwise unusable land. When the government refused, Captain Jack left the Klamath Reservation, taking about 150 Modoc people with him.

By the fall of 1872, tensions escalated between Modocs, civilians and the military — marking the beginning of the Modoc War.

The Modocs retreated to the nearby lava beds, in a place now known as Captain Jack’s Stronghold.

An ancient home in the lava beds

The lava beds near the city of Tulelake, California, make up a small region of Medicine Lake Volcano, the largest shield volcano by volume in the Cascade Arc, dating back half a million years. Numerous eruptions have created expansive lava flows stretching hundreds of miles through California’s Siskiyou and Modoc counties.

Indigenous people have lived in the area for thousands of years. According to the National Park Service, archaeologists estimate petroglyphs and other rock art in the region may date back at least 6,000 years.

In this undated image, several petroglyphs are displayed on an ancient cliff at Petroglyph Point in Northern California.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

Lava Beds National Monument

Today, the Stronghold is part of the Lava Beds National Monument. The monument covers over 70 square miles and contains more than 800 known caves, one of the largest concentrations of lava tube caves in North America.

This undated image of Merrill Cave is an example of one of the hundreds of lava tube caves spread throughout the Lava Beds National Monument in California.

Courtesy the National Park Service

Modoc tribal member Cheewa James worked at the monument as a ranger. She says that when the military decided to follow Captain Jack, it didn’t understand how the Modocs would use the landscape to their advantage. “It’s important to realize the ruggedness of this terrain where this war was fought. If you look out at the rocks, the military had never experienced anything like this. They completely fell apart. Their gloves were shredded. Even their shoes.”

James is a descendant of one of the war leaders and can trace a direct line to these lava fields. “My great-grandfather Shack Nasty Jim, his wife Anna was pregnant during the war, and that child was literally born in the stronghold. It must have been a terrible thing.”

The lava beds offered refuge against the military. The small band dug in, holding off the Army for months, winning almost every battle.

“— Devery Saluskin, Klamath Tribes, Lava Beds National Monument, June 2011It wasn’t just men fighting against men. It was the Army against families.”

Imagery of war

As the war dragged on, local photographer Louis Heller and pioneering British photographer Eadweard Muybridge documented the events.

In this image from 1873, soldiers inspect Captain Jack's Stronghold at the end of the Modoc War.

Courtesy of the National Archives

Through almost 100 known images, the photographers captured soldier training exercises, landscapes and cave fortresses, as well as, eventually, the Modoc War prisoners — making it one of the most documented conflicts of the American West.

At a presentation at the Merrill City Hall on “Imagery of War,” archaeologist Eric Gleason explained how stereoscopic 3D images brought the war into households across the country. “It was remarkable for the time. I don’t think any other battles had had that type of coverage.”

Mass-produced photographs became available to the public as postcard-sized cabinet cards, while images appeared in newspapers and magazines. However, many images were staged, including a picture of a Warm Springs scout posing as a Modoc warrior with a gun.

This image from 1872-1873 shows a photograph by Eadweard Muybridge next to a lithograph used in Harper's Weekly, of a Warms Springs scout posing as a Modoc warrior.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

“It was used as the basis for a sketch in Harper’s Weekly with the caption ‘Modoc brave lying in wait for a shot.’ It was not a Modoc at all but the art was pretty good,” Kepple said.

Murder and surrender

For months, as the Modocs held out against the military, the public seemed to support the Indigenous cause, with newspaper letters and editorials expressing sympathy for Captain Jack’s battle for a small piece of rocky land.

That all changed on April 11, 1873, when a group of Modoc leaders attacked a peace commission meeting under a flag of truce, killing Brigadier Gen. Edward Canby and Reverend Eleazer Thomas and leaving others injured. Canby’s death marked the highest-ranking military official — and one of the only generals — ever killed by Native Americans.

The government cracked down hard, calling for swift punishment.

“— The New York Times, 1873Public opinion is almost unanimous against the peace policy, owing to these recent occurrences, and the majority believe in exterminating the outlaws.”

Before long, the small band of Modocs faced a force of nearly 1,000 men, composed of military soldiers and civilian volunteers.

The Modocs suffered few casualties but, cut off from the nearby Tule Lake, struggled to survive in the lava beds. Eventually, they gave up their stronghold, simply walking out in the dead of night. The soldiers didn’t know until the following day that the Modocs had slipped away.

In this image from 1873, Franks Illustrated Newspaper cover depicts the Modoc people leaving their stronghold during the Modoc War in Northern California.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

“When the Modocs left the stronghold, they were in desperate need of water, they needed food. They were malnourished and of course they had children and women with them,” James said.

Under such desperate conditions, infighting among the Modoc band led some to turn against Captain Jack. In the end, he turned himself in.

“Psychologically the Modocs were becoming a very shattered people. And it was at that time that the dissension with the Modocs began to happen.” James said.

“— Lt. William Henry Boyle, Modoc War veteranCaptain Jack surrendered at 10:30 a.m. Jun. 1, 1873, saying that his legs had given out.”

Research in the past decade shows that Captain Jack may not have understood the terms of his surrender.

The Klamath County Museum acquired three small diaries containing previously unknown eyewitness accounts of Captain Jack and other Modoc prisoners, including transcripts from interviews on the night before the execution.

One entry describes Jack as telling military officials he had expected to be returned to the Klamath reservation: “After I had surrendered and was taken to the Fort, I had no thought of being punished, for I know my heart was right. I thought to come and live at peace on Klamath Lake.”

Kepple says the diaries record the last interview in the hours leading up to the execution, “So these were chilling comments for us to read.”

“— Capt. Jack, Oct. 2, 1873I have always tried to be a good man.”

Meanwhile, other research from a newly rediscovered written account claims Captain Jack and fellow leader Schonchin John may have tried to escape prison.

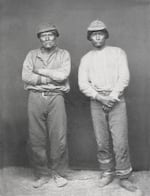

This photograph from 1873 shows Modoc leaders Schonchin John and Captain Jack at Fort Klamath, Oregon.

Courtesy of the National Archives

Gleason said during the presentation, “We learned just about a month ago that they almost succeeded in breaking their shackles. Someone discovered that they had just about got through those shackles and tried to escape.”

Crimes against the United States

In July 1873, the U.S. Army charged six Modoc leaders with war crimes against the United States for the peace commission attacks.

James says many called the trial illegal. “The jury was made up of the officers, the very men that they had fought against.”

Rep. John K. Luttrell of California demanded an investigation into the war, writing in a letter of protest, “The war was caused by the wrongful acts of bad white men.”

The military commission found the Modoc men guilty of murder in violation of the laws of war. It was the only time the Army charged Native Americans with that crime.

A public execution

On Oct. 3, 1873, groups gathered at Fort Klamath. The crowd included soldiers, tourists, locals and hundreds of Modoc and Klamath tribal members forced to watch their kinsmen die.

“— San Francisco Chronicle, Oct. 3, 1873The execution is to be as public as possible so that they may be forever terrified by the spectacle.”

This composition of Modoc prisoner photographs from 1873 shows Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Boston Charley and Black Jim at Fort Klamath, Oregon.

Courtesy of that National Archives

Four men went to their deaths that morning: Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Boston Charley and Black Jim.

President Ulysses S. Grant commuted the sentences of two men — Barncho, also called One-eyed Jim, and Sloluck — to life sentences in Alcatraz.

After the hanging, the military had the bodies decapitated and the men’s heads sent to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C., a common practice at the time. Two thousand Native American skulls would eventually end up there for study.

Today, eight acres of the original military outpost are part of the Klamath County park system. Fort Klamath Park includes a small museum, a replica of the guard house and the four graves of the Modoc men executed in 1873. It receives more visitors than any other Klamath County park.

The aftermath and legacy

On Oct. 12, 1873, 27 wagons loaded with 155 Modocs — 42 men, 59 women and 54 children — departed Fort Klamath, Oregon, toward a reservation 2,000 miles away in “Indian Territory” in what is now Oklahoma. Some prisoners died along the way.

In 1909, they were allowed to return to Oregon and join the Klamath Tribe. Many did, though some chose to stay in their new home as part of the Modoc Nation of Oklahoma.

Alcatraz prisoner Sloluck was eventually allowed to rejoin the Modocs in Oklahoma.

“— Taylor Tupper, Klamath Tribes, June 2011Our bloodline is strong. Our people are strong. And we are not going away.”

This image from 1873, shows a group of Modoc tribal members relocated to Oklahoma.

Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society

“Oregon Experience” behind the scenes

In 2011, OPB’s “Oregon Experience” produced a one-hour documentary on the history of the Modoc War.

Having grown up in Chiloquin, home of the Klamath Tribes, working on this documentary was especially important to me. I was able to spend time with descendants I had grown up with, their parents and elders who have now passed on, learning and sharing their stories.

In 2019, after seeing the documentary, Oregon state Sen. Fred Girod proposed a resolution commemorating the Modoc War. It passed on April 2 of that year, “honoring those who lost their lives in the war, and expressing regret for the expulsion of the Modoc tribe from their ancestral lands in Oregon.”

Today, the program is used in many classrooms and was most recently shown in March 2023 at the Ross Ragland Theater in Klamath Falls. Unfortunately, my snow tire chain changing days are (hopefully) long behind me, so when an unexpected storm hit the Cascade Mountain pass, I was unable to attend.