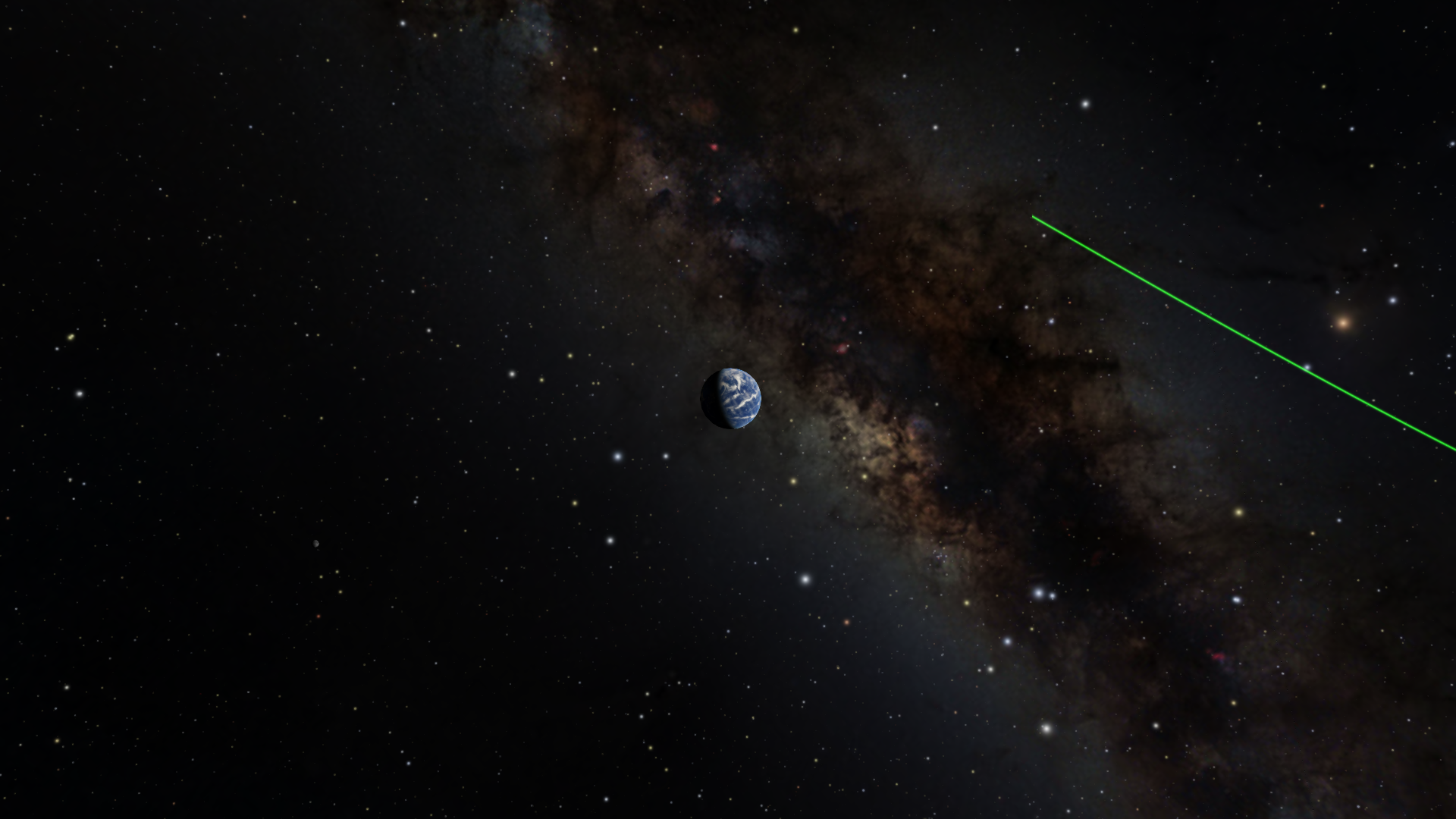

This illustration released by the University of Washington shows the orbit of 2022 SF289 (green) at its closest approach to Earth.

Courtesy of Joachim Moeyens/University of Washington/OpenSpace

Asteroid hunters

One of human-kind’s favorite existential threats is an asteroid hitting the Earth. It’s a scenario that’s made so much money for so many movie studios (and prompted one of ASNF’s favorite movie reviews). It’s what ended the dinosaurs. And just last year, NASA was able to use its planetary defense technology to hit an asteroid in space and change its trajectory.

But before we can deflect the Earth-ending asteroids, we have to figure out where they are. This could become much easier, thanks to research out of the University of Washington.

Astronomers there have created an algorithm that can scan images of the sky to detect potentially hazardous asteroids. Old detection programs needed at least four images of the same part of the sky per night to ID the asteroids. The new algorithm requires only two, making the likelihood of detection far greater.

The researchers tested the new code on a group of images that hadn’t turned up an asteroid previously. This time they found 2022 SF289, a 600-foot asteroid that will pass within 140,000 miles of the Earth — close enough to be put on the watch list.

The new algorithm will be deployed at the U.S.-funded Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, which is slated to begin full operations in late 2024. The researchers estimate that there are still thousands of potentially hazardous asteroids in the solar system, just waiting to be detected.

The 2022 SF289 asteroid discovery was announced in the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Electronic Circular here.

This image released by the University of Oregon shows the Rimrock Draw Rockshelter in Eastern Oregon. UO archeologists have dated a human-made tool to more than 18,000 years old, which would make it oldest human artifact ever excavated in North America.

Courtesy of the University of Oregon

North America’s earliest humans

Scientific evidence is starting to pile up: humans came to North America far earlier than we initially thought. For a long time the earliest arrival date was about 13,500 years ago. Earlier this year, Oregon State University archeologists dated arrowhead-like points found in Idaho to nearly 16,000 years ago.

Now researchers at the University of Oregon have dated human objects to more than 18,000 years ago.

The discovery came on Bureau of Land Management land in Eastern Oregon. The archeologists used several clues to hone in on that date. First they IDed a layer of volcanic ash from Mount St. Helens deposited 15,400 years ago. Below that layer (going back in time), they uncovered animal teeth from a now-extinct North American camel. In layers below the teeth, they found a multi-edged stone scraper (presumed human-made) with what tested to be preserved residue of bison blood.

The researchers were able to radiocarbon date the camel teeth to 18,250 years back. And this means that the stone tool found in layers below the teeth is likely older than that.

If the evidence holds, this human object could be the oldest human artifact ever unearthed in North America.

Read more about the discovery here.

Kids and allergies

Allergies are exceedingly common. In the United States, more than a quarter of all kids develop allergies, a number that’s increased over the past decades.

Researchers at the University of British Columbia and BC Children’s Hospital think they may know why. It has to do with the microbiome — the communities of microorganisms that live inside the digestive tract.

They tracked the microbiome through stool samples of more than 1000 kids, and half of them developed one or more of four common allergies by the age of 5: eczema, asthma, food allergy and hay fever. They found a distinctive bacterial signature associated with all of the allergy types.

The maturation of an infant and its gut microbiomes are so linked that the microbiome makeup can usually be used to accurately predict the age of a kid. But in the children that would go on to develop allergies, their microbiomes were immature. The specific signature is caused by an insufficient intestinal barrier that allows your immune system to go ham on all those beneficial bacteria.

The findings could lead to ways to predict and eventually prevent childhood allergies.

This illustration released by the Pacific Northwest National Lab shows the novel heat recovery component of the hydrothermal liquefaction system (HTL). The new technology has the potential to enable HTL deployment.

Courtesy of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Read the paper in the journal Nature Communications here.

Sludge is the enemy

The search for green (or at least greener) energy sources had led to a push for new ways to generate fuels. One carbon-neutral option now emerging commercially is called hydrothermal liquefaction — essentially using wet biological material, adding a little heat and pressure, and generating something akin to crude oil. In about 20 minutes, it can do what normally takes the Earth millions of years to accomplish underground.

The Vancouver metro area in British Columbia is poised to open a new plant in 2025 to convert the city’s sewer waste into transportation fuel. It will be the first of its kind in North America.

Researchers at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory are thinking about a problem that systems like Vancouver’s could face: the raw material sludge gumming up the pipes. The new method uses heat recovered later in the production process to steam heat the raw fuel and make it less viscous. When the material flows better, it’s less likely to bake onto the walls and foul up the system. The researchers say the technology will make the industrial process cleaner, more reliable and more competitive with existing fuel production systems.

The research was presented at the American Chemical Society Fall Meeting.

This photo released by Oregon State University shows a massive late-stage algal bloom on Upper Klamath Lake. The turquoise color is algal pigments being released during cell death.

Courtesy of OSU College of Science

Toxic algae sniffer

One of the ways that the effects of climate change are showing up in the Pacific Northwest is the increased presence of toxic algae blooms in our ocean, rivers and lakes. The challenge is that sometimes the microorganisms produce toxins and sometimes they don’t — and you can’t tell by just looking at the water. Guessing incorrectly can lead to rashes, gastrointestinal illness and sometimes death.

Researchers at Oregon State University have figured out how to predict toxic by-products of one of the main freshwater culprits: cyanobacteria (more commonly, and incorrectly, referred to as blue-green algae). Working at Upper Klamath Lake, they analyzed volatile organic compounds (VOCs) wafting up from the water. They found that different and detectable groups of VOCs appeared when the cyanobacteria started producing toxins.

The scientists say this kind of specialized water sniffing could lead to prediction and detection methods that are cheaper and able to cast a wider net than current toxic algae monitoring methods.

Read the results in the journal mSystems here.

In this monthly rundown from OPB, “All Science. No Fiction.” creator Jes Burns features the most interesting, wondrous and hopeful science coming out of the Pacific Northwest.

And remember: Science builds on the science that came before. No one study tells the whole story.