Rancher Jeanne Carver visits some of the sheep on the Imperial Stock Ranch in June 2022. She hired scientists to measure how much carbon is added to the soil on the ranch with changes to grazing patterns and crop production.

Cassandra Profita / OPB

Rancher Jeanne Carver threw her leg over a fence lining her property in Central Oregon.

“Let me go first,” she said. “It’s snake season.”

Watching for rattlesnakes, she led the way into a field her family converted back into grassland after a century of crop production.

Homesteaders cleared the rocks and plowed this field to plant grain and hay on what is now the Imperial Stock Ranch, which grazes sheep and cattle and grows wheat and hay in Maupin.

“This was tough country to farm,” Carver said. “They had to pick areas where they had more soil than rocks.”

Traditional dry land farming practices eroded and degraded the soil, she said, because every other year the ground would lie fallow and bare.

“So you left thousands of acres with no plants in it exposed to both wind and water erosion with runoff,” she said.

Carver and her family have spent decades reversing the damage, reseeding crop fields with permanent plants and changing their farming practices to avoid tilling up the soil.

“What we’ve done is return it to a more natural state,” she said, “to encourage the land to be healthier, richer.”

They’ve also changed the way they graze their sheep and cattle, moving them more frequently and intentionally from pasture to pasture across 50 square miles.

Sheep graze on Imperial Stock Ranch rangeland in Maupin in June 2022. The ranch is measuring how much carbon is added to the soil under a planned grazing program.

Cassandra Profita / OPB

In 2020, Carver hired a team of scientists to study the results of all these changes. Several years of data show that the combination of restoring grasslands, changing grazing patterns and producing crops without tilling didn’t just improve the soil health on the ranch. It also pulled significantly more carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and into the ground.

The data from 21 sampling sites on 32,000 acres of land show the Imperial Stock Ranch practices are adding 1.86 tons of carbon per acre to the soil every year, offsetting all of the greenhouse gas emissions from its own operations and banking an additional 60,000 tons of carbon in the soil.

That’s enough for Carver to make some extra money from a practice known as carbon farming. Last year, the ranch entered a 10-year contract to sell carbon credits through Agoro Carbon Alliance.

It’s an example of a promising strategy for reducing climate change in Oregon and beyond. Federal and state leaders are offering incentives for working farms and ranches to change their management practices in ways that sequester more carbon in the soil, and they’re looking at just how much storage potential might exist across millions of acres of land.

“It begins with the land winning,” Carver said. “If that’s happening, then all the rest of us win. The farmers are winning. The people who purchase the offsets, and every citizen is winning because we are helping on the climate challenge.”

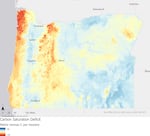

A preliminary map of which soils in Oregon can hold more carbon in the top 20 centimeters. Red indicates oversaturated soils where additional organic matter will quickly decompose and return to the atmosphere. Blue indicates undersaturated soils with potential to protect additional carbon for decades. Top soils in the Cascades and Coast Range are generally oversaturated while those in the Willamette Valley and nonmountainous regions of Eastern Oregon tend to be undersaturated.

Courtesy of Drew Childs, Oregon State University

A reason to measure ranchland health

Imperial Stock Ranch was forced to change its marketing strategy in 1999, when the processor that had bought its wool for a century closed its U.S. operations and moved offshore.

“Nobody knew what to do,” Carver said. “My husband looked at me and said, ‘If we don’t find our own markets for what the sheep give us, they’ll be gone off this ranch.’”

After they lost their wool market, Carver and her husband, who died in 2021, shifted from commodity sales to direct marketing. To make new sales, they started telling the story of how they’d improved the environmental health of their ranch — from the salmon streams to the soil.

“My husband always believed that the healthier the natural resource base, the healthier your harvest and therefore the healthier your bottom line,” Carver said.

Sheep graze on Imperial Stock Ranch rangeland.

Courtesy of Jeanne Carver

Carver said their story fit nicely into the culture shift that attracted people to farmers markets.

“Suddenly, the stewardship of this ranch became important to people,” she said. “It was reconnecting people to the provenance of the product.”

But it wasn’t until the London Olympics in 2012 that the strategy really took off. At the time, there was growing concern that the U.S. Olympic team uniforms were made in China. Ralph Lauren was searching for a way to make uniforms in the U.S.

“And I got a phone call,” Carver said. “Six months later, I got a purchase order for the largest amount of yarn I had ever had.”

In 2016, Imperial Stock Ranch became the first sheep ranch in the world to be certified under the Responsible Wool Standard, an official recognition of sustainable sheep grazing practices.

Related: WATCH: Oregon Field Guide | Imperial Stock Ranch

“It’s been more successful than I could have ever imagined,” Carver said.

Now, a growing number of wool customers want to know the climate impact of the products they’re buying. In 2019, one company asked Carver a troubling question.

“They actually straight-out asked me: ‘Do you guys harm the Earth while you’re raising these animals?’” Carver said. “How do you answer that question? So, it became apparent to me that the next logical step was to actually measure the carbon footprint of our agricultural operation.”

How to measure a carbon farm

Carver hired John Talbot, a scientist who recently retired from the Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station, to start taking those measurements about three years ago.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has a farm and ranch carbon-capture calculator called Comet-farm that helps landowners account for carbon sequestration in the soil based on their grazing and land management practices.

“It gives you a really neat way to say my operation emitted this much carbon, but in return I’m putting this much carbon back into the soil through my practices so I can offset that,” Talbot said.

Talbot also measured the results through soil sampling at 21 different locations on the ranch.

Imperial Stock Ranch grows wheat and grazes both cattle and sheep, Talbot said, so the ranch has to account for methane emissions from the animals and their manure as well as nitrous oxide emitted from fertilizer applications. But it also has thousands of acres of land with the potential to sequester carbon.

A field on Imperial Stock Ranch where scientists have collected soil samples to measure the changes in carbon concentration as the ranch has changed its farming and grazing practices.

Courtesy of Jeanne Carver

“You can seed different plants like legumes, you can apply compost, you can change your grazing intensity, you can do cover crops,” Talbot said. “There’s all kinds of things that we can try to see what effect it has on soil carbon.”

Talbot said to keep the system in balance, with plants taking carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and putting it into the soil, a rancher has to keep grazing animals moving so the plants can keep growing.

“And that’s more work, right? Just moving the animals around,” he said. “It costs money.”

Some of their extra costs could be covered by the extra money Imperial Stock Ranch stands to make by selling carbon credits to companies that need, or want, to offset their own carbon emissions.

Carver said this kind of carbon farming offers a valuable new income stream for her business, and she’s leaning into the idea by building a network of 10 ranches across the West that are all measuring carbon sequestration in the soil on 2.6 million acres of land.

One day, Carver said, her business, Shaniko Wool Co., could sell the carbon offsets to the companies making clothing out of their wool and market those clothes as carbon neutral.

“This is the vision,” Carver said. “This is the hope. And we’re motivated to do that by the increasing climate crisis.”

Climate programs offer funding

Over the past year, federal and state climate programs have announced funding to motivate more farmers and ranchers to follow Carver’s lead.

Oregon state Sen. Michael Dembrow, D-Portland, visited Imperial Stock Ranch last year in the process of developing legislation that incentivizes landowners to store more carbon in the soil.

“It was gorgeous out there,” he said. “It got me thinking more about just how little thought most of us give to the soil right under our feet. What potential does it have to help us with almost everything that we are looking to do to help our planet?”

Dembrow helped pass a climate action bill this year that creates financial incentives for landowners across the state to implement “natural climate solutions” on their farms and ranches.

The bill allocates funds to encourage activities like planting trees or cover crops that sequester carbon in the soil and help the state reach its climate goals, which aim to reduce emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.

“When most people think about climate action, they think about their cars and their stoves and industry, but they don’t think about our agricultural practices,” Dembrow said. “They also can be real agents of change.”

Oregon State University professor Markus Kleber, left, and graduate student Drew Childs collect soil samples from a crop field near Boardman, Ore., in March. They plan to collect samples from 110 sites in Morrow, Gilliam and Sherman counties to build a map of soil carbon potential across the state.

Cassandra Profita / OPB

The kinds of activities that store more carbon in the soil can also improve the overall sustainability of the land, Dembrow said. Plus, the landowner can earn extra money through carbon credits.

Nora Apter, climate program director for the Oregon Environmental Council, said agriculture generates 12% of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, and Oregon’s climate action plans could help reduce that. But she sees a risk in selling carbon credits based on sequestration in the soil because it allows someone else to avoid reducing their climate pollution.

“We shouldn’t be selling sequestration … instead of reducing emissions,” she said.

To fight climate change effectively, she said, the world needs both emissions reductions and carbon sequestration on working farms and ranches.

“Not one or the other,” she said. “We need to do all of it.”

If landowners in Oregon receive funding intended to sequester carbon and mitigate climate change, then selling those reductions as offsets for polluters arguably undermines the policy goal, Apter said.

“They’re still doing harm,” she said. “You’re continuing to stave off the inevitable, which is a transition to a clean energy future.”

The state climate action bill calls for setting voluntary goals for increasing carbon sequestration on natural and working lands, measuring progress and maintaining an inventory of the carbon being sequestered on land across the state.

This year, the Natural Resources Conservation Service received $20 billion to help farmers and ranchers pay for “climate smart” agricultural practices through the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act.

“Our role is to help a farmer get to that level where they’re implementing the practices that’ll help sequester that soil,” Ron Alvarado, state conservationist for the NRCS in Oregon, said.

Alvarado said about 70% of all the land in the U.S. is privately owned.

“In order to address climate change, we need voluntary conservation to work, right?” he said. “These private landowners are stewards of the ground. They’ve been working it for generations. We need them.”

How much carbon can Oregon soil hold?

Oregon State University soil scientist Markus Kleber digs a pit in a crop field near Boardman in March to sample the soil and measure its carbon storage potential.

Cassandra Profita / OPB

In the middle of a farm field near Boardman, Oregon State University soil scientist Markus Kleber is digging a 3-foot hole to measure how much carbon the soil can store in a part of the state where scientists don’t have much data to go by.

The field is one of 110 agricultural sites in Eastern Oregon that Kleber and graduate student Drew Childs are sampling this year as part of a larger effort to map the carbon storage potential of Oregon soils.

“The state has an interest in putting more carbon into the soil,” Kleber said. “If the soil is already stuffed with carbon, it doesn’t make sense to try to get more into it.”

The science of storing carbon in the soil is complicated, Kleber said, and to measure the potential they need to gather a variety of soil composition data and apply an algorithm. Digging 110 holes is the easy part.

“The word storage is not the best word to describe the situation,” Kleber explained. “The soil is a living system where the organic matter is flowing through and not just being deposited. We want to harvest products that the system is producing, so we need the carbon to do work. We don’t just want it to sit there.”

In fact, he said, just leaving carbon in the soil and not putting it to use would be a waste.

Oregon State University graduate student Drew Childs, left, collects soil samples from a farm near Boardman with OSU professor Markus Kleber in March.

Cassandra Profita / OPB

“There’s a lot of carbon in these potatoes that we are taking away from the soil when we harvest them and eat them,” he said. “What we don’t want is to treat the soil as some sort of a dump.”

Rather than thinking of the soil as a storage tank for carbon, he said, “think of the soil as a pipe and the carbon flowing through that pipe. What we want is to make the pipe thicker.”

More carbon moving through that underground pipe means less carbon in the atmosphere.

Kleber said the same kinds of practices that put more carbon in the soil would also help solve other environmental problems, such as the loss of biodiversity and soil degradation worldwide.

“Putting carbon in the soil should absolutely be incentivized,” he said. “It makes the soil more resilient to unexpected things like drought. It makes the soil more productive. It makes the soil a better water filter.”

However, it is possible to go overboard, Kleber said, and too much carbon can lead to water pollution problems through runoff.

“Our tool is going to be a means to prevent that,” he said.

‘This is where we can make a difference’

Oregon State University soil scientist Markus Kleber collects soil samples from a crop field near Boardman in March. His lab can measure the amount of carbon in the soil and calculate how much more it can hold.

Cassandra Profita / OPB

After digging their pit, Kleber and Childs took soil samples to their lab in Corvallis, dried them out in an oven and collected a series of measurements to determine how much more carbon they could hold.

Using data from across the state, their map will identify areas where more carbon can be sequestered in the soil through land management changes such as planting cover crops or doing less tilling on crop fields. That will tell the state where carbon farming could be used to offset greenhouse gas emissions and help reach climate goals.

So far, the map shows topsoils in Eastern Oregon and the Willamette Valley have a lot more room for carbon while the Cascades, Coast Range and Blue Mountains do not — they’re oversaturated.

“We were actually a little bit surprised by how much room we predict in the Willamette Valley topsoils,” Childs said.

Across the state, for every soil type, they’ve found the lower-level subsoils all have capacity to hold more carbon.

Oregon State University professor Markus Kleber holds a soil sample from a crop field near Boardman. It's part of an effort to create a map of the carbon storage potential in Oregon soils.

Cassandra Profita / OPB

In France, government leaders have set a target for offsetting a portion of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions by storing more carbon in the soil.

“I think that is something people are very excited about,” Childs said. “That’s something that this project will let us do.”

Kleber said the map of Oregon soils will be a helpful guide to areas that can hold more carbon, but it could be costly because it will take a ton of sampling or a new technological development to measure the amount of added carbon across a whole landscape.

“It’s not as easy as you hope it would be, but it’s not hopeless,” he said. “It needs to be tried. And then if it works, let’s do it.”

Kleber’s findings from the samples he collected in the crop field near Boardman show that soil can hold an additional 4.8 tons of carbon per acre.

“I would not have expected that,” Kleber said. “Landscapes like this are the place where we can actually make a difference.”