Editor’s note: Throughout 2023, OPB is taking a deep look at the biggest social and economic challenges facing Oregon today — their origins, their impacts and possible solutions. This week, we’re looking at Oregon’s housing cost crisis.

Isobel Charle and Noa Curtis spent much of their early adulthood living with upwards of a dozen people at a time. The two friends met in the Portland area in their 20s, when they were living in “intentional communities” — living spaces in which a large number of people share responsibilities. Sort of like a chosen family, as opposed to a biological one.

Noa Curtis, left, and daughter, Remy Curtis, talk with housemate Isobel Charle in their home in Northeast Portland, Ore. June 12, 2023. The two friends chose to purchase a home together as a solution to rising rent costs.

April Ehrlich / OPB

After years of group living — and enduring regular hours-long roommate meetings to hash out chores and interpersonal dynamics — Charle and Curtis wanted a chance to downsize the number of people they lived with. They were also tired of being at the whim of increasing rents, though neither could afford a home on their own.

“So we made that decision to buy a house together,” Curtis says, sitting in what is now their living room in Northeast Portland, which they closed on in November last year.

Although they had a solid decade-long friendship, the decision to make such a major investment with a friend wasn’t easy. Charle recalls feeling fear and uncertainty: “Am I really going to do this? Am I ready? Is this going to work?”

Ultimately, this seemed like the best option for two people with modest incomes. Charle is a substitute teacher and freelance journalist and Curtis is a medical social worker.

“I was like, ‘This is as close as I’m ever going to come to being able to do this,’” Curtis says. “And it felt like the market is just going to get more and more expensive. I don’t know if my salary is going to match that.”

Across the state — from big and mid-size cities to small, rural towns — Oregonians are straining under the pressure of an increasingly unaffordable housing market. First-time homebuyers are looking outside expensive cities, causing suburbs and small towns to experience their own shrinking housing stock and increase in prices. Some homebuyers, like Curtis and Charle, are getting creative by purchasing homes with friends.

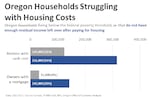

Renters are the hardest hit. More than half of renters in the state don’t have enough money after paying rent to afford other basics, including food, child care, internet access and transportation. Because the state’s housing inventory is so limited — Oregon simply doesn’t have enough units for the number of people who need them — there are limited rental vacancies, so landlords can raise rents with few repercussions. As a result, Oregon is among states with the lowest supply of rentals that are affordable to people at or below poverty levels. (A unit is considered affordable if it costs someone 30% or less of their income.)

More than half of Oregon renters don't have enough money after paying rent to afford other basics, including food, child care, Internet access and transportation.

Graphic courtesy of the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

“We have the worst affordability,” said state economist Josh Lehner. “Low vacancies and high prices is indicative of a housing shortage. And I think that’s clearly what we’ve been in for a while now.”

As housing has become more unaffordable, more people have been pushed into homelessness. In a 2022 national homelessness report, Oregon had a 22% increase in people experiencing homelessness between 2020 and 2022 — the second highest increase in the country, behind California. An additional 2,591 people in Oregon became homeless during those two years.

Housing experts say homelessness is intertwined with the availability of affordable housing in a given area. And the crux of Oregon’s housing affordability issues, Lehner and other local researchers say, is decades of underproduction. Oregon just hasn’t been building enough homes for everyone. And while much of the country is experiencing a housing crunch, Oregon is among the worst cases: It ranks fourth in underproducing housing, behind California, Colorado and Utah.

It’s tempting to oversimplify how Oregon’s housing market failed to keep up with demand. Some people blame the state’s stringent land-use laws for restricting the ability to expand where new construction could go. Others blame the private sector’s control of real estate, or developers who only want to build large single-family homes, or bureaucratic permitting processes.

“It’s a really complex issue, and there are all these different parts, and pointing the finger at one thing — that’s what makes us lose sight of the overall systematic issues,” said Rebecca Lewis, an associate professor in planning public policy and management at the University of Oregon.

Lewis is among several researchers who have been digging into studies and data to help policymakers figure out how Oregon reached a point of being 140,000 housing units short of what’s needed — and what it will take to dig the state out of this hole.

They say the state’s history of restrictive housing laws and laissez faire approach to increasing and diversifying housing stock — as well as a national shortage of builders, rising materials costs and stagnant incomes — are among a web of factors impacting people’s ability to pay for housing. Researchers say there isn’t a quick fix to undo decades of underbuilding and a nationwide culmination of socioeconomic stressors. Still, there are things policymakers and regular Oregonians can do now to help ease the strain.

How we got here

When Oregon lawmakers passed the state’s ground-breaking land-use law back in 1973, the nation was emerging from a revolutionary environmental movement.

The federal government had just passed the Clean Water Act, and people across the world organized their first Earth Day celebrations. Locally, Oregonians had their own conservation movement, one that was more of a reaction to the suburban sprawl infecting their southern neighbor, California. There they saw farms and forests eaten up by large residential tracts of single-family homes, permanent changes to the state’s landscape. Oregonians were determined not to let that happen here.

Related: OPB podcast 'Growing Oregon' dives into history, impact of state's strict land use laws

So Oregon lawmakers passed Senate Bill 100, which established boundaries for urban development as a tool to protect open spaces. If a local government wanted to expand its urban growth boundary, say to make room for more homes or businesses, it would need to ensure the change conformed with statewide planning goals. Since the 1970s, those 19 codified goals have governed how the state utilized land for agriculture, forestry, economic development, open spaces, natural resources and more.

The tenth goal, covering housing, says cities and counties need to regularly inventory their buildable lands and accommodate future housing needs.

“But the way that that’s actually been implemented at the local level for a really, really long time has not actually fulfilled the goal itself,” said Ethan Stuckmayer, senior housing planner at the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development, the agency that oversees statewide planning

Goal 10 didn’t capture the nuance of the state’s housing needs and how they would change over time. It didn’t, for instance, call on governments to encourage the creation of multiple types of housing beyond single-family homes. While it tasked local governments with regularly publishing their housing strategies, it didn’t give them a time frame — some cities and counties operated on the same plans for decades without revisiting ever-changing housing dynamics. It also didn’t provide counties and cities with the funding they’d need to complete those plans — a struggle for rural areas with fewer taxpayers. Goal 10 also didn’t address Oregon’s historically racist and classist housing policies that restricted homeownership among people of color, leading to a wealth gap that continues to exist today.

Oregon’s response to single-family zoning

In the early 1900s, American cities started implementing single-family zoning policies in certain neighborhoods. These policies, which got their start on the West Coast, only allow single-family homes to be built there — so no apartment buildings, duplexes, or condos, forms of housing that are usually more affordable. The earliest single-family zoning policies in Oregon also came with racial covenants that specifically barred homeowners from renting or selling to people of color.

By segregating multifamily housing units from single-family homes, cities effectively segregated communities by class and race, and they prevented families of color from growing the generational wealth that came with owning property within high-value neighborhoods.

Over time, homeowners in these zones pushed for more control over the look and feel of their neighborhoods to ensure they continued growing property values. Cities created ordinances governing everything from how many garages a home needed to have to the overall lot size. In turn, single-family homes became larger and more expensive to build, and small single-family homes for new families began to vanish. Residential construction started requiring more land, even as it became increasingly scarce.

Two construction workers add in wood panels at the Modera Woodstock construction site in Southeast Portland on July 7, 2023. Designed by Leeb Architects, the multi-use building will provide 194 housing units and around 6,000 square feet of retail space.

Caden Perry / OPB

Policymakers are only recently coming to terms with the effects these policies have had on housing availability. In 2019, Oregon grabbed national attention after it became the first state to eliminate most exclusive single-family zoning statewide. The new law requires cities to allow duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes, townhomes and cottage clusters (small detached homes that typically share a courtyard) in areas zoned only for single-family housing, depending on the size of the city.

That year state lawmakers also required cities to develop strategies for increasing housing production, and it provided them with funding to create those plans. The same law tasked state agencies with producing a regional housing needs analysis outlining how the state could address housing shortages regionally.

“I think 2019 was this year where we were maybe a decade into a severe shortage of housing units — feeling the crunch, feeling the the burden of a small supply of housing that’s not adequately meeting the demand,” said Stuckmayer, the lead planner for the new housing division. “It was a coalescing of all of those issues, with increased conversation about the rising cost of housing and the inequities that resulted.”

The coronavirus pandemic the following year worsened Oregon’s housing struggles in many ways. Oregon’s poverty rate increased as the lowest-earning workers lost pay. The number of workers entering the construction industry plummeted as people opted for more flexible remote jobs, making it harder to build homes necessary to meet demand, and supply chain issues made it harder and more expensive to get construction materials even when developers could find enough workers.

During those early pandemic years, a record number of Oregonians, particularly Millennials, chose to form families, leading to a housing formation boom and skyrocketing demand for housing. Some economic factors played a role — wages increased in 2021 as a result of a labor shortage, and three rounds of pandemic-related stimulus checks helped young people save enough money for mortgage down payments.

By 2022, researchers published the Oregon Housing Needs Analysis, saying the state needed to build 555,000 more housing units to meet demand over the next 20 years. In response to the report, Gov. Tina Kotek, just after taking office, issued three states of emergency related to housing. One called on the state to build 36,000 homes a year — an 80% increase from current production. The executive order also created an advisory council to put the plan to action.

“This level of production is very ambitious,” Kotek said at the council’s inaugural meeting in March. “It will require all of us working hard, exhibiting bold action to accomplish this goal.”

A “Mass Casita” is lifted into place, one of two parts that will be Scott and Barbara Benedict’s new home, June 7, 2023 in Otis, Ore. The 1,136 square foot home is one of six in a prototype project designed and developed by Hacienda CDC, aiming to determine if modular housing built with mass timber could be a solution in Oregon’s housing shortage.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

Lawmakers this year also passed a massive $200 million package to help cities address the housing crisis. In addition to money for homelessness services and to help people stay in their current homes, the package requires cities to set building targets for buyers at different income levels, and it streamlines the process for expanding urban growth boundaries. Senate Republicans’ six-week walkout over the summer paused the state’s headway on housing policies. When lawmakers returned, they pushed forward a flurry of additional housing bills, including stricter rent-control measures and help for first-time homebuyers.

“Oregon is absolutely leading the nation on the work that we are doing on housing policy and investment,” said Lorelei Juntunen, president and CEO of ECONorthwest, a consulting company often hired by the state for housing research.

But it could take years, possibly decades before these policies to produce results, and that doesn’t help the tens of thousands of people who need homes today.

“We are in such a large deficit right now that all of the planning and regulatory moves in the world are not going to get us out of the hole,” Juntunen said. “We just simply have to have to put some money into it.”

Potential next steps for policymakers

While experts agree that Oregon needs more housing for people at all income levels, the biggest hole the state must fix is affordable housing. That’s something the state can’t rely on the private sector to build, not without financial incentives.

Construction began at Glisan Landing, an 137-unit affordable housing complex in Portland's Montavilla neighborhood, in June of this year. The development is a joint venture between Catholic Charities of Oregon, Related Northwest and the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization (IRCO).

Caden Perry / OPB

Because of what it costs to build a new home — land values, building materials, permitting and labor costs have all risen sharply in recent years — new construction is rarely affordable to people with low incomes. By federal standards, a housing unit is considered affordable when it costs someone 30% or less of their income. Over time, new homes may become more affordable as they age, but that can take decades.

The Oregon Housing Needs Analysis calls on lawmakers to make significant investments in publicly supported affordable housing. That could look like increasing “gap funding” — basically, paying developers subsidies so they can pursue affordable housing projects without losing money. Oregon already has programs for that — the LIFT homeownership and rental programs, for instance, helps fund projects that create more affordable units to rent or buy. But at current funding levels, the LIFT programs can produce only a small fraction of what’s needed, according to the OHNA report.

Construction also takes time; builders can’t just plop a housing subdivision on an empty piece of land. They need what’s called “buildable land” — that is, land that has access to water, sewer, roads and electricity. It’s usually up to cities and counties to provide that infrastructure, but many local governments can hardly afford maintaining the infrastructure they already have. That struggle is particularly acute in rural areas where there are fewer taxpayers, and in coastal areas where roads and water systems are more strained.

“Sewer systems degrade, asphalt needs to be repaved, and so on, and cities are going to face a huge financial obligation to do the capital improvements and maintenance on those facilities,” said Robert Parker, co-director of the Institute for Policy Research and Engagement at the University of Oregon.

Infrastructure might also become more expensive as the state focuses on squeezing more homes within urban-growth boundaries.

“Nobody’s thinking about the long-term asset management of the infrastructure that’s serving all of these low-density neighborhoods,” Parker said.

The federal government used to fund local infrastructure, but that funding significantly declined after the 1960s. Since then, cities and counties have mostly handled those costs. Because Oregon has fairly strict regulations on what cities can collect through property taxes, local governments pass infrastructure costs onto developers through fees called system development charges. A study by ECONorthwest found system development charges are increasing faster than inflation because cities and counties have so few alternative funding sources. These fees in effect make housing more expensive, because it costs more money for developers to build, who then pass those costs onto buyers. The study proposes local governments take a “nuanced approach” to such fees — wherein they could provide reductions or exemptions for affordable housing projects.

What Oregonians can do

Housing affordability may be a topic heavily reliant on policy, and thereby policymakers, but the general public has a history of impacting what gets built, and where. It’s how the term “not in my backyard,” or NIMBY, came about, implying vocal groups of people who use public meetings to oppose new projects in their neighborhoods. When it comes to affordable housing, NIMBY-ism is often fueled by fear and prejudices and can perpetuate housing segregation.

State economist Josh Lehner said sometimes the message is subtle: Someone will say they support the creation of more housing, just not in a certain residential block, or they support an apartment building, but only if it’s a couple of stories shorter.

“It’s understandable where some of those viewpoints might come from on an individual level,” Lehner said. “But at a societal level, it’s clearly resulted in an underbuilding of housing, as well.”

A “yes in my backyard” movement has emerged in recent years, including one in Bend, where people take to public forums to support housing developments and ensure public officials are doing what they can to encourage affordable housing.

Related: Portland group works to make wealth redistribution a reality through real estate

Homeowners can also help add to housing stock. If they have the space and resources to build, many Oregon cities and counties have relaxed ordinances related to accessory dwelling units on single-family lots. If that’s not feasible, renting out a bedroom can also help. A nonprofit called Home Share Oregon helps connect homeowners with roommates, including seniors who need affordable housing.

Stephen Price, in his home in Beaverton, Ore., June 22, 2023. Price relocated from Texas and was having difficulty finding affordable housing where he felt safe. He worked with Home Share Oregon, a program designed to match homeowners who have spare bedrooms, with Linda Scott, who had rooms available in her home.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

Tess Fields, executive director of Home Share Oregon, says the organization’s main goal is to promote a culture of homesharing.

“Prior to World War II, or even the 1930s, people had boarding houses all the time,” said Fields. “But when we got into the 80s, it really kind of fell out, and we started hammering the single-family home mentality.”

Fields said single-family zoning laws have helped push Americans into this housing crisis. She says they’ve also fueled a loneliness epidemic, as more people over time opted to ditch multigenerational households, where they could raise children alongside grandparents and extended family members, for insular nuclear family models. With that, Fields said, Americans lost a sense of community.

For Isobel Charle and Noa Curtis, the two friends who purchased a house together, home sharing wasn’t only a means of gaining the economic benefits of owning a home; it was a way to create a sense of belonging. They say they plan to build additional units on their property to rent out to friends and family.

“I feel, generally, the structure of the strict nuclear family that we have doesn’t work for me,” Charle said. “I find it limiting and isolating. I love to be around people. I love the challenge of figuring out how to live together and work together and make decisions together. It taps into a part of our humanity.”

This examination of Oregon’s housing obstacles was written and reported by April Ehrlich, edited by Anna Griffin and produced for the web by Meagan Cuthill, with photo editing by Kristyna Wentz-Graff and photos by April Ehrlich, Caden Perry and Kristyna Wentz-Graff. This series exploring both the biggest problems facing Oregon and potential solutions is sponsored by the Oregon Community Foundation. And none of OPB’s journalism happens without you. Help us tell more stories like this one — and ensure stories like this reach as many people as possible — by joining as a Sustainer now.