Johnnie Ray

Ray family

Seventy-one years ago, Oregon farm boy Johnnie Ray shook the music world when he encouraged fans to “let your hair down and go on and cry.”

In 1951, Ray’s breakthrough song “Cry” shot to the top of the Billboard record charts. Within weeks of its release, the song hit No. 1 for both pop and rhythm & blues sales. The record’s flip side, “the Little White Cloud that Cried,” reached No. 2 on the pop charts. Overnight, the relatively unknown young man from Oregon became a jukebox sensation and one of the first teen idols.

“He kind of exploded with ‘Cry,’“ says Ray’s friend and last manager, Alan Eichler. “He had all of these hits. He was a big star, and he played the big nightclubs. He had a few scandals along the way, but his stardom was huge.”

Today, most people don’t know the name Johnnie Ray or his lasting influence on modern pop music.

“— Alan Eichler, Johnnie Ray’s last managerMusically, he’s considered the link between Sinatra and Elvis, and that’s because he brought a rhythm and blues feeling to pop music…. His performing style was that of the future.”

John Alvin Ray grew up in the Willamette Valley community of Hopewell, just outside of Dallas, Oregon.

“The women of Polk County just loved Johnnie Ray,” says Bette Jo Lawson of the Polk County Historical Society. “My mom wouldn’t let me watch anything of Elvis’ but she just loved Johnnie Ray. He was OK.” The historical society’s museum has a small display of Johnnie memorabilia, including a picture of Johnnie and Elvis together.

Oregon Experience examines the life and legacy of 1950s teen idol Johnnie Ray. Watch the documentary here:

Eichler says before Elvis was a household name, he regularly came to watch Johnnie’s Las Vegas performances. “Elvis studied Johnnie, and he acknowledged that.”

“There’s a story that they didn’t like each other but that’s not true,” says Ray’s nephew Roger Haas.

Elvis and Johnnie Ray Image courtesy Polk County Historical Society, Ray family collection

Polk County Historical Society, Ray family collection

Throughout his life, Ray remained close to his family and returned to Oregon often. Haas says, “It was always a good time when Uncle Johnnie came home. He always had the greatest Christmas presents. The best ones always came from Uncle Johnnie.”

Ray often called Oregon home, but Haas says as a young man, the budding star was eager to leave, “He definitely could not have been happy here in Oregon. I think he just never really felt like he fit in.”

Ray told reporters that he felt isolated from an early age, partly due to undiagnosed hearing loss. He received his first hearing aid as a young teenager and started singing professionally soon after. In 1941, he began appearing on the Portland radio show “Stars of Tomorrow” along with future actress Jane Powell. Over the next few years, he sang for local war bond drives and played for tips in regional bars. All the time, he was also writing music.

In his early 20s, he made his way to Detroit’s Flame Showbar. The club featured some of the era’s hottest jazz and rhythm and blues acts. Ray performed with legendary musicians like Ruth Brown, Laverne Baker, Maurice King, and his hero, Billie Holiday.

“— Johnnie Ray radio interview, 1967If it hadn’t been for the Black community, there really wouldn’t be any Johnnie Ray around. At that time, I was supported by virtually all Black people who were my friends. I didn’t have any white friends. I was literally fed and clothed and kept in that community.”

It was during this time that Ray ended up in jail for soliciting a male police officer. He reportedly asked the plain-clothed officer back to his room for a drink. Ray pled guilty and paid a $25 fine. In 1959, he faced another solicitation arrest.

Eichler says, “Johnnie was gay at a time when being gay was not accepted. If the general public had known he was gay, it would have been damaging. But I think people in the business knew.” Ray was briefly married but had long-term relationships with both women and men.

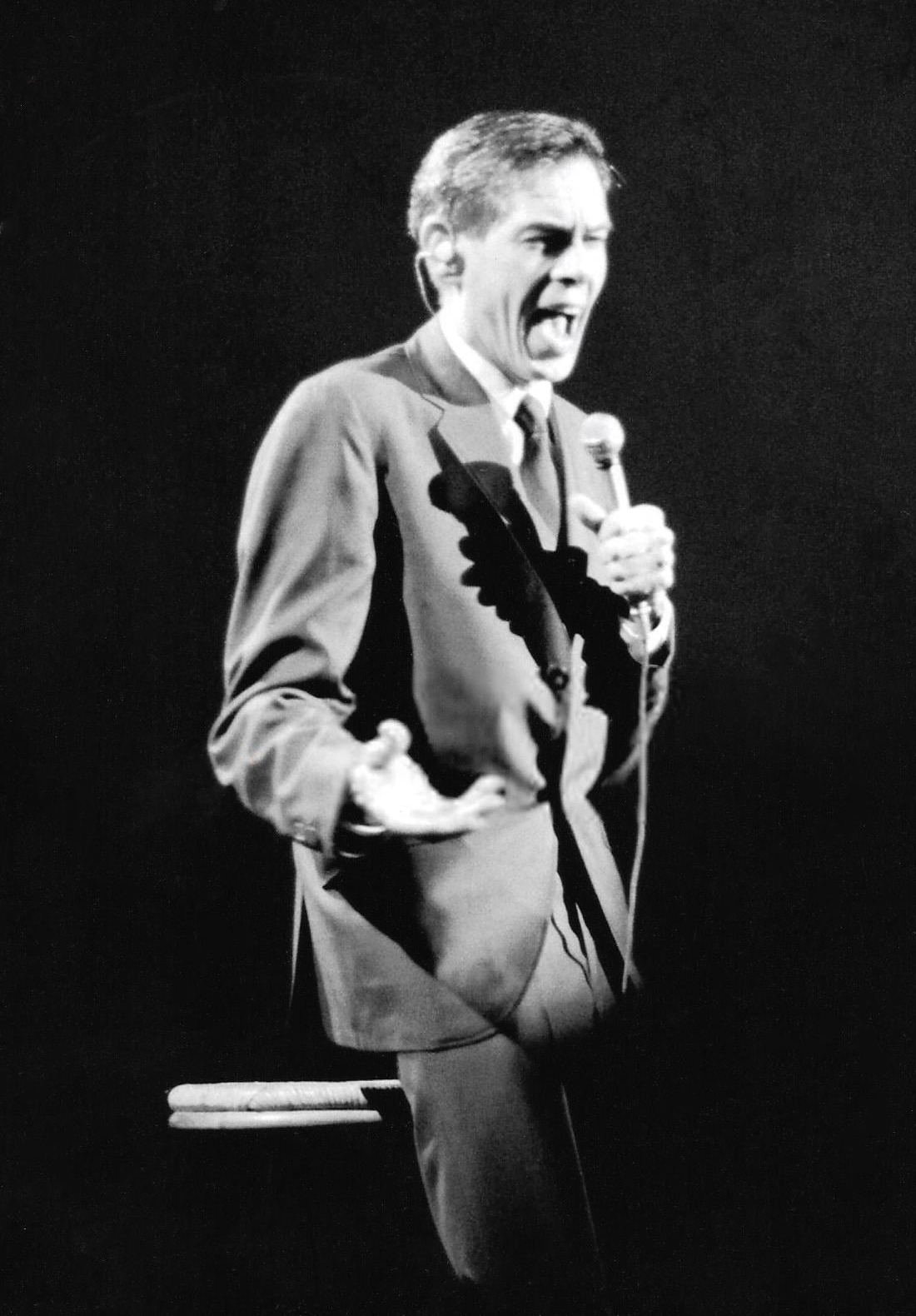

Johnnie Ray's emotional performances earned him the nicknames Mr. Emotion, the Cry Guy, and the Prince of Wails. AP Wire image, 1956

Historic Images

In 1951, Ray signed a contract with Columbia subsidiary Okeh Records. His first recording featured two original songs — “Tell the Lady I Said Goodbye” and “Whiskey and Gin.” Both became regional favorites with local disc jockeys.

His next release changed everything. “Cry” was an overnight hit, earning him a gold record and millions of fans. His emotional singing, along with his sweat-drenched, full-body performances, thrilled — and shocked — audiences.

The press dubbed him “the Prince of Wails,” “the Cry Guy,” “Mr. Emotion,” and “the Nabob of Sob.” In 1952, four of his songs made Billboard’s 30 top-selling records for the year.

After the success of “Cry,” Columbia moved him from the small Okeh to its main recording label. Under the direction of the so-called “hitmaker” Mitch Miller, Johnnie recorded a series of pop standards.

“Mitch Miller had his own ideas of pop music, and he did not like rock and roll. So nobody at Columbia recorded rock and roll. ” Eichler thinks this sabotaged Ray’s career, “He was like a raw talent with rhythm and blues roots, and they turned him into white bread.”

Throughout the 1950s, Ray made numerous TV performances and, for a time, hosted a variety show in the United Kingdom. His concerts drew thousands of fans, with record-breaking performances at New York’s Copacabana and the Hollywood Bowl. There were other hit songs, but none of them topped the charts like “Cry.”

By the late 1950s, Johnnie Ray’s star was already dimming as Elvis, and other bold new acts, dominated radio airwaves. Though he faded from the limelight, Ray still maintained loyal fans, especially in the UK and Australia. He continued to perform right up until his death from liver failure in 1990.

ADDITIONAL VIDEOS

On the brink of stardom

In this short video clip, young Johnnie Ray performs his original song “Tell the Lady” at a nightclub in New York, 1951.

Johnnie on TV

Johnnie Ray performs the Irving Berlin song “You’d Be Surprised” on the TV show “Arthur Murray Party,” 1954.

RELATED CONTENT

RESOURCES

Books

“Cry, the Johnnie Ray Story,” by Jonny Whiteside. Barricade Books, 1994

“Rocking the Closet: How Little Richard, Johnnie Ray, Liberace, and Johnny Mathis Queered Pop Music,” by Vincent L. Stephens. University of Illinois Press, 2019

“Johnnie Ray: Beyond the Marquee” by Tad Mann. Author Solutions, 2006

Interviews

Myles de Bastion, musician & CymaSpace founder

Terry Currier, Music Millennium owner

Alan Eichler, Johnnie Ray’s manager

Roger Haas, Johnnie Ray’s nephew

Bette Jo Lawson, Polk County Historical Society

Gary Norris, Johnnie Ray archivist

Randall Ray, Johnnie Ray’s nephew

Vincent L. Stephens, Boston University, associate dean for diversity and inclusion