An investigation by the King County Sheriff’s Office into a ballot drop box surveillance effort organized by conservative activists has wrapped up without criminal charges.

However, the case technically remains open and the findings of the voter intimidation inquiry have been shared with the FBI, according to the sheriff's office.

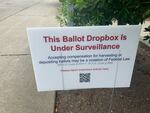

Signs like this one at the Broadview library branch in north Seattle popped up at some King County ballot drop boxes in July. They prompted concerns about voter intimidation and ultimately an investigation by the King County Sheriff's Office.

Jim Brunner / The Seattle Times

A copy of the investigation, which the Northwest News Network and The Seattle Times obtained through a public records request, said the decision to end the active investigation followed a meeting on August 17 between the sheriff's office, the King County prosecutor's office and King County Elections.

“It was concluded that further investigation was not necessary at this time but the case could be re-opened if similar behavior is seen during the next election,” Detective Keith Gaffin wrote in his report.

Gaffin also wrote that a copy of his report had been shared with an FBI special agent “to assist in determining if the FBI would be further pursuing this case.”

In an email, Seattle FBI spokesperson Steve Bernd said his agency typically neither confirms nor denies the existence of an investigation.

“Please keep in mind, a review of allegations does not necessarily result in the opening of an investigation, Bernd wrote.

Similarly, the Washington Attorney General’s office said on Wednesday it does not disclose pending investigations, but added it does not have a “referral in this matter.”

The sheriff’s office investigation was triggered in late July, prior to the state’s August 2 primary, when signs appeared near some Seattle-area drop boxes that said “This Ballot Dropbox is Under Surveillance.” The signs warned of criminal penalties for ballot "harvesting." In Washington it's not illegal to drop off another person's ballot.

The signs also included a QR code to report "suspicious activity." That code linked to a page on the King County Republican Party's website. The chair of the party, Mathew Patrick Thomas, disavowed the effort. In an interview with The Seattle Times at the time, he said he was not aware of the signs being placed and had instructed party activists "to stop doing this."

“As KCGOP Chairman, I was not consulted regarding this activity and was not made aware of it until I was contacted separately by the Director of King County Elections, Julie Wise and media,” Thomas told the newspaper.

The signs were quickly removed. But not before Jessica Fuller of Seattle spotted one near the drop box at her local library in the Ballard neighborhood. Fuller was one of several citizens who alerted King County Elections to the signs.

“I think it’s disingenuous, it’s under the guise of protecting democracy, but it’s not,” Fuller said in an interview on Wednesday. “It’s intimidating voters.”

But neither Fuller nor any of the other witnesses contacted by the sheriff’s office said the signs had dissuaded them from lawfully voting — a potentially key element to proving voter intimidation.

“I am glad that no voter has reported feeling so intimidated that they didn’t vote,” said King County Elections Director Julie Wise in a statement.

Wise added: “I believe the parties involved, as well as any others looking to interfere with voting in any form, have been put on notice — attempts to dissuade voters will be met with action.”

Wise said her office would remain “vigilant” about similar efforts heading into the general election this fall.

Separately, also in July, a statewide effort that called itself "WA Citizens United to Secure Ballot Boxes" recruited volunteers to stake out drop boxes to watch for "suspicious activity."

To date, the individuals behind that effort have not revealed themselves or publicly discussed their efforts — and they were not a subject of the sheriff's investigation. Attempts to contact the organization have been unsuccessful.

In a statement in July, U.S. Attorney Nick Brown of the Western District warned that voter intimidation is a federal crime and said “any attempt to harass or discourage citizens from voting at our state’s secure election drop boxes will be investigated and prosecuted in federal court.”

In a follow up statement Wednesday, Brown said: "Our office stands at the ready to work with our law enforcement partners to investigate and prosecute threats of violence, hate crimes, and efforts to intimidate voters or those who are tasked with ensuring free and fair elections in our state.”

According to a Georgetown University School of Law fact sheet, voter intimidation is defined as activity "that is intended to compel prospective voters to vote against their preferences, or to not vote at all, through activity that is reasonably calculated to instill fear."

That can include, the fact sheet says, “Spreading false information about voter fraud, voting requirements, or related criminal penalties.”

It's not illegal to observe a ballot drop box and, in fact, there’s a tradition of partisan election observers doing so, especially during times when election workers are picking up ballots. However, the groups engaged in the primary election drop box surveillance were not official observers.

Since the 2020 election, some supporters of former President Donald Trump have falsely claimed that ballot drop boxes are a vehicle for committing election fraud. The movie “2000 Mules” by conservative author and commentator Dinesh D’Souza has fueled the conspiracy theory that ballot “mules” stuffed drop boxes with fake ballots in key swing states.

That allegation — which has been widely debunked — is what appeared to animate the drop box surveillance program in King County. Included in the sheriff's report was a screenshot from a message thread about putting up the signs at drop boxes. One of the messages read in part: "Let's put the FEAR OF GOD in some ballot-trafficking mules!"

Election officials and experts in Washington state and nationally say vote by mail and ballot drop boxes are a secure method for voting. Even if someone did put fake ballots in a drop box, there are mechanisms in place, including signature checks, to ensure only lawful ballots are counted.

This story was reported with Jim Brunner of The Seattle Times.