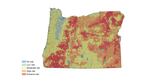

The Oregon Wildfire Risk Explorer map, created by Oregon State University as part of a new wildfire policy directed by Senate Bill 762, outlines wildfire risk at the property ownership level across the state.

Oregon Wildfire Risk Explorer

The Oregon Department of Forestry is hitting the reset button on its plans to finalize a map of wildfire risk on 1.8 million tax lots across Oregon.

On Thursday, the agency announced it will withdraw the wildfire risk map released in June and cancel the notices to property owners placed in high or extreme fire risk categories.

“We know how important it is to get this right,” Oregon State Forester Cal Mukumoto, said in a statement. “We knew the first iteration of an undertaking of this scale and complexity wouldn’t be perfect, but we have been and continue to be committed to improving the map and our processes related to it.”

The announcement comes after thousands of public comments and complaints about the state-mandated map poured into the forestry department’s inbox. The agency has received 750 appeals from property owners who say they were mislabeled on the wildfire risk map and more than 2,000 comments. It has a backlog of 1,700 voicemails from the public that haven’t been heard because the forestry department staff is also working to fight several fires across the state.

Property owners are blaming the state for lowering their property values, raising their insurance rates and mistakenly classifying properties in high fire-risk zones in the new map.

At a virtual public information session on July 27, more than 1,200 people tuned in to hear a litany of complaints about a lack of information about how properties were categorized and what a high fire risk classification will mean for them financially.

“For some people this could be catastrophic if they can no longer afford their homeowners insurance, and they could lose their home,” a Southern Oregon resident said at the session. “Can anybody tell me how I’m going to be impacted financially? What’s going to happen with my insurance? No. … There’s no protection for the homeowners. There was absolutely no consideration for how impactful this could be.”

The mapping process is a required part of a wildfire preparedness package state lawmakers passed last year in response to the wildfires that burned 4,000 homes and more than a million acres of Oregon in 2020.

The idea was to identify properties that face the most wildfire risk and apply new fire safety requirements in high-risk areas to protect homes and communities from future fires.

State Sen. Jeff Golden, D-Ashland, championed the bill as a way to prepare the state for hotter, drier summers and more fire risk that come along with climate change. In response to residents complaining about the wildfire risk map in a public information session last month, he said the lawmakers who voted for Senate Bill 762 last year decided they should move quickly and “correct as we go” rather than wait years to start taking precautionary steps.

“Our state and our communities are in imminent danger,” he said. “We are trying to defend our state from destruction, and I don’t think anybody can say that that’s made up when you look at a dozen cities in Oregon and California that have been destroyed.”

The Oregon State Fire Marshal and the Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services are developing rules for clearing defensible space around homes and applying wildfire hazard building code standards for new construction in high-risk areas. The new wildfire risk map will determine where the upcoming rules will apply.

Map identifies properties facing high fire risk

The map released in June placed large stretches of Central, Eastern and Southern Oregon in the red “extreme” wildfire risk category based on weather, climate topography, vegetation and nearby buildings.

The map also placed about half of the state’s 1.8 million tax lots in the “wildland-urban interface,” a designation for homes and communities that are more vulnerable to wildfire because they are intermingled with forestland and wilderness areas.

ODF spokesman Derek Gasperini said there are also numerous complaints about the accuracy of the map – especially when it placed neighboring properties into different wildfire risk categories or mischaracterized the vegetation around a property.

“There are some legitimate questions about inconsistencies in how or why a particular community has different risk properties that are right next to each other and we want to be able to better explain that,” he said. “There may be places where we didn’t get it quite right.”

The abundance of comments also flagged broader problems with the amount of information the public has to understand their risk category, Gasperini said, and it highlighted the fact that the legislative deadlines for producing the map didn’t give the state enough time to gather input from the public.

“We’re hoping to provide a better understanding of what goes into the categorization of risk so that they can understand what goes into that rather than just, ‘Here’s the map. You’re high risk.’ without much explanation why.”

Gasperini said he couldn’t cite any specific examples of property misclassifications that led the state to withdraw the map, but officials have held three public information sessions and have heard a lot of similar “anecdotal input” from around the state about inconsistencies in the map.

“We want to take that seriously, hit pause on the map and investigate what may be anomalies, or what may be a gap in understanding,” he said. “We want to take both of those as real concerns. We just want to make sure that the settings and the way that the map is done makes sense to folks and that we have it right.”

One story of a duplex that was placed in two different fire risk categories has been cited by numerous critics, Gasperini said, and technically it is possible for that to happen if the two sides of the duplex fall into different tax lots. One side of the duplex might face higher fire risk because of weather data such as wind direction and the topography of the surrounding landscape.

“One will be more at risk because that’s the direction that the fire is going to go because of conditions,” he said. “You wouldn’t see that by standing on the ground. But the tool is getting at that level of detail that people may not see or understand.”

Mary Bradshaw's home in Elkhorn, Feb. 26, 2021. Bradshaw's fire-hardened home was one of the only ones in the area that survived the 2020 Beachie Creek fire. New building codes would require more home builders to use more fire-resistant materials in high-risk areas.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

Mukumoto, who heads the department of forestry, said his agency will be working with the mapmakers at Oregon State University to refine the map and “improve the accuracy of risk classification assignments” for individual properties.

The state has “a window of opportunity” before any new rules connected to the map are finalized, he said. The withdrawal of the map will not affect the timelines for other state agencies that are developing new building codes for construction in high fire risk areas and requirements for clearing flammable material around homes and structures.

Gasperini said a revised map and a new round of notifications to property owners in high and extreme risk categories should be ready by the end of the year, which means people will then have more details about what new rules they will be required to follow.

The agency is effectively canceling the current appeals process, but Mukumoto said officials will be reviewing the information in the appeals “and using it to identify additional areas where we may need to take a closer look at the data.”

A new appeals process will launch after the release of the revised map, Gasperini said, but the timeline for that process has yet to be defined.

The second time around, the agency is planning to release the map before it is finalized and give the public more time to weigh in on it. A public information session on the map was scheduled for next week in Redmond, but that session might be canceled.