Monkeypox is spreading in Oregon, with 32 confirmed and suspected cases up from just six last month.

“I can definitively say that’s an undercount,” said state epidemiologist Dean Sidelinger at a media briefing Wednesday. Many cases of the rash are subtle enough that it may not occur to doctors to test for the virus, he said.

While Oregon’s first case was linked to travel out of state, Sidelinger says more recent cases don’t have an obvious source, indicating that people are getting it locally. To date, all of the known cases have been in men. Cases have been reported in Clackamas, Washington, Multnomah, and Lane counties.

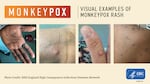

Few people in Oregon have been hospitalized due to the virus, but some patients have reported the lesions cause extreme pain that can make it difficult to eat or drink. Monkeypox, also known as hMPXV, is a milder relative of the smallpox virus that can cause painful sores and flu-like symptoms. It’s rarely fatal.

The infection, which has typically occurred in tropical rainforest areas of central and west Africa, is now causing outbreaks in more than 40 countries. The global outbreak has grown to nearly 14,000 cases, including 5 deaths.

However, due to the characteristics of hMPXV, most Oregonians are not at risk of getting an infection.

The infection generally transmits through prolonged skin-to-skin contact with a person who is actively sick, or through contact with contaminated bedding or clothing. It can potentially transmit through respiratory droplets, but only with very extended — think three hours or more — face-to-face contact.

Monkeypox is spreading in Oregon, with 32 confirmed and suspected cases up from just six last month. Recognizing symptoms early, limiting skin-to-skin contact with others, and seeking vaccination if you’re at highest risk, can help protect your health.

U.K. National Health Service via U.S. CDC

“This is not spread nearly as easily as Covid-19,” Sidelinger said. “It is not spread from people without symptoms, or from a casual passing by.”

Because most of the cases so far have been among men who have sex with men, particularly those who have multiple partners or anonymous partners, state health officials said they are focusing on helping those people protect themselves.

“It happens to be in this social network and sexual network of people,” said Kim Toevs, with Multnomah County Public Health.

Multnomah County has 15 confirmed cases, the most in the state.

Vaccine shortage

Toevs said a lack of vaccines and a shortage of staff for vaccination clinics are the two biggest obstacles to controlling the outbreak. A vaccine is available but in short supply. It’s being distributed to states based on their population and an estimate of the higher-risk population, based on data related to HIV cases.

If the hMPXV vaccine is given to people within four days of being exposed to the virus, it can prevent them from becoming sick and potentially infecting other people. It also prevents infection if it’s given before a person is exposed.

The county has received about 50 doses reserved for people who know they have been exposed to someone with a confirmed case. In addition, the county received 350 doses that officials are giving out in clinics today and Saturday to people at the highest risk of exposure to the virus.

Every appointment has been taken, and the county now has a waitlist of over 500 people who were screened as high risk and eligible for the vaccine.

Another shipment of vaccines should arrive next week, with 50 more doses for people with known exposure and about 500 doses for high-risk individuals.

The difficulty of finding health care staff who can give vaccines is also slowing the response to the outbreak, Toevs said. If Multnomah County officials can identify a few more vaccine teams to help distribute the shots, they may be able to get more doses allocated by the state.

Stopping the outbreak

With vaccines still in short supply, public health officials are asking the medical community for help identifying cases and encouraging gay, trans, and queer people who have sex with men to take additional steps to protect themselves. Multnomah County has developed recommendations specifically for gay, trans, and queer Oregonians. And the state health authority is encouraging doctors to order the test for hMPXV when they see patients with unexplained rashes.

Recognizing symptoms early, limiting skin-to-skin contact with others, and seeking vaccination if you’re at the highest risk, can help protect your health, Toevs said. Also, she said: Ask any new partners about a rash.

“Don’t have sex with a new partner in the dark, so that you can see if they have a rash on their skin before you touch them. And make sure you have some contact information for them. That way if they do get sick or you get sick, you can let each other know,” Toevs said.

Being able to notify partners if you develop a rash is extremely important because then the public health department can help get them a vaccine.