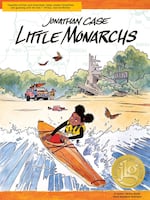

Portland cartoonist Jonathan Case has written a upbeat post-apocalyptic adventure tale for kids.

courtesy of Jonathan

Portland cartoonist Jonathan Case has illustrated Batman comics for DC and illustrated a graphic novel about the Green River Killer. His newest book is somehow both lighter and darker at the same time. “Little Monarchs” is an upbeat post-apocalyptic adventure tale for kids. Case joins us to talk about the book.

The following transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. The cartoonist Jonathan Case has created Batman comics for DC and a graphic novel about the Green River Killer. His latest book is somehow both lighter and darker at the same time. It’s called ‘Little Monarchs.’ It is set in a post-apocalyptic Oregon and focuses on a young girl’s mission to find her family and save humanity. It is part adventure story, part ecology lesson and part survival primer. It’s also a tender and beautifully illustrated book. Jonathan Case, welcome to Think Out Loud.

Jonathan Case: Thank you so much for having me.

Miller: Can you describe the setup, the sudden sun sickness that wipes out most mammal life on earth before your book starts?

Case: The premise is that 50 years before 2101 when the book starts, there’s this thing that happens. There’s no specific explanation but sun sickness wipes out mammal life largely across the earth because it interferes with the heart rhythms of those particular animals and people. So unless they’re deep underground, maybe in a subway or a cave or something, their heart arrhythmia was the end. The mission that the little girl and the biologist are on is to find essentially some medicine that they can develop into a vaccine to share with people and provide some long-term relief from the sun sickness. They have a medicine that’s working, but it’s not good enough to share with other people because it only lasts a short amount of time. And it’s based on monarchs and what they derive from the milkweed plant.

Miller: So the two main characters are able to be out in the sun, out during the day, because they have this medicine they can make, as you noted, that’s derived from monarch butterflies. Everybody else – they’re called Deepers – what are they doing?

Case: They’re surviving underground. That’s the slang term for them – just people who are surviving underground and living mostly a nocturnal life. After the sun is well set, they come out and do their farming, their night ranges, they’re called in the book. They have a certain perimeter of night range that is generally what you could expect, how far they could travel away from their site before they would have to turn around and come back to safety. So, on the maps in the book, you’ll have these night ranges that are marked out in places around the Western States, and the characters sort of have to weave in and out of those with the sense that there might be danger if they’re inside of somebody else’s range because they can’t predict what other people are going to do.

Miller: What was your inspiration for this book at the beginning?

Case: I was afraid of becoming a parent about 12 years ago, and I thought, ‘I need more practical skills.’ Artists aren’t known for having a whole lot of those. And I wanted to get out of my office and have some real adventures. I thought if I could follow something like the monarch butterfly migration, that would take me into these real locations where I would then gather coordinates, geolocation data, and I would put all of that and the scenes wherever I went into the book. So, step by step… [for example] I might do a drawing of a beach at Pacific City Oregon, say. Then in the book, the photo reference and those geolocation coordinates, all of that is in there so that people can see it in the book, see how it’s transformed through the imagination of drawing. But then they could actually go there. They could actually follow the characters step by step, moment by moment. So all of the scenes in the book take place logically across the geography of the Western States.

Miller: When you say 12 years ago you were afraid, or felt unprepared, to be a parent, what was it about getting out and following monarch migration that made you feel like that would better prepare you?

Case: I think I wanted to have an adventure that I could translate into a book. I would share the book with my kids. I would make this book for my kids, but then I would also be able to come full circle and say to them, ‘So these are real places that you can go to. You can have a sense of agency in the world. And here are some skills like knot tying, star navigation, science..’ All of that is woven into the narrative of the book. But hopefully if a kid picks this up, they won’t feel like they’re being forced to learn something. They just learn it naturally because it’s being presented through the vehicle of the characters in the story. I guess that was my scheme, and we kind of came again full circle to it this year. We took a book tour around the Western States for the book and took our kids along and took along a milkweed seed, native milkweed seed, wherever we went and distributed that in hopes of giving something back to the monarch migration, supporting it.

Miller: Milkweed because that is what butterflies rely on, and it figures prominently in the book. Why focus on monarchs in particular? They figure prominently in this in a lot of different ways, scientifically and narratively as well. What first attracted you to monarchs?

Case: At first, it was just the science and the practical nature of their migration. It is pretty wondrous in and of itself, that it takes them three generations to fly north. Each generation lives about a month, maybe six weeks. Then in the fall, when they feel the cold weather coming on, this really amazing thing happens where they just stop growing up. They just choose to stay juvenile, strong… They’re like super monarchs. They live eight times longer than any of those three generations that preceded them, and they’re able to make the entire journey back south. So that alone is incredible, but when you think about how they’re flying to a place they’ve never been to – they’ve never had a parent saying, ‘This is the way you go.’

Miller: Not even a grandparent or great grandparent.

Case: Yeah, exactly. They’re so far removed.

Miller: It’s mind-boggling.

Case: Yeah. There’s an eternal connection there. I think that’s part of why they’re a symbol in Day of the Dead where they represent, in that tradition, spirits visiting, coming back to us – especially people we’ve lost too soon.

Miller: As an Oregonian, it was a pleasure but also maybe a shock, to see all these real places in Oregon. You mentioned some of them: Pacific City and Brookings and then heading east all the way to Crystal Crane Hot Springs, a super lovely place. But we see them in your book, in the disrepair of a post apocalypse combined with the existing or maybe increased natural beauty because there are fewer humans around to get in the way of it in various ways. I’m curious if, when you were in those places, you were doing a kind of apocalypse-imagining tour.. If you were there but imagining what it would be like if most humans had died.

Case: I guess I would say I was using my imagination. I wasn’t so specifically focused while I was out on those locations on that part of the story. Because I did the trips and the science research first, and then I kind of took a lot of it home and started crafting the story. But mostly I had my characters. I was thinking, ‘What are my characters doing here? What’s their mission? Why are they following these butterflies? What would Elvie, the little girl, be thinking about this place?’ So I was always kind of using my imaginary friends like… you’re outside, you’re outside to play, only your canvas is a little bigger than your backyard. It’s the whole Western States. I guess I had a fairly positive kind of energy about it because I was thinking about, what would it be like to be a little girl with a greater sense of opportunity to travel in the world than a lot of kids have. Because she doesn’t have to worry about other people. Really the tragedy doesn’t loom large for her in the same way that it would for us because that’s all she knows. And really the natural world is front and center. It’s all around her, so I wanted that to be the focus of the book: her exploring nature, her being empowered to get out in it.

Miller: There’s a gentleness that pervades the whole book. There are rollicking adventures, and some characters don’t survive. I don’t think that’s a spoiler. I won’t give away what happens. But the central relationship of this smart, spunky girl named Elvie and then the biologist, this cantankerous but kind woman named Flora – they’re this great duo – that’s really at the heart of the book. Their relationship is full of respect and love and gentle ribbing. Why did you infuse a book about the almost end of human society with such tenderness?

Case: Well, I guess it kind of goes back to my initial… the place that I was at when I started working on the book and thinking about becoming a parent. I was wondering how I was going to navigate having a mission with then having to care for a little human and investing in both. It’s a lot of work to make these graphic novels. It’s a process of many years. I was figuring that out for myself, so I thought, if I could translate that into this book, maybe I could sort of figure it out a bit – figure out a way for myself to move forward, as a creative person, as a person with a mission, and as a parent. I guess that’s where I began. As far as the tenderness, I guess that’s just the grace of then becoming a father while I was still working on the book and maybe being able to put more of that reality into it than I would have if I had done it real quick and got it done before they arrived. My kids are… My oldest daughter is 10 years old now, so she’s as old as the lead character. I never expected that when I started it, but that’s how it went.

Miller: One of the hallmarks of your book and a lot of stories about post-apocalyptic life is that it’s nearly impossible to survive on your own, but it’s just about as hard to know who to trust. In your book, the main characters can’t necessarily trust the Deepers, the people who live underground and can only come out at night. It made me think that, in a less dramatic way, that’s true about regular life, too. I’m curious how you think about the need for human relationships and the challenge of them.

Case: Yeah, that’s well said. I grew up with a lot of isolation, a lot of time on my hands to be out in nature, and I was an introverted kid. So I think that introversion sort of fuels the characters, especially the scientist character, who’s especially wary of other people and is teaching this little girl to be as self-reliant as she can be. But, at a certain point, self reliance does break down. I think there’s a balance to be struck between being prepared and then also recognizing that often the people around us are our best resource. I think a lot of the preppers who move out into the boonies forget that you really do need your tribe in a lot of cases.

Miller: Or you need to make a new one…

Case: Right.

Miller: …which is a lot of what this book is about. You include in the book a little boy named Otis, who I’ve learned is named after your late son. He died when he was 2. How did you decide to put a version of him in this book?

Case: Well, the book had already become this dance between what was real and then what was imaginary. When I lost my son, everybody told me, ‘Oh, you’ll remember everything, don’t worry.’ But I just knew that I wouldn’t, and I was just afraid of not having anything to hold onto. So I debated for a while because I didn’t know if I’d be up, in the post-creation phase, for talking about it a lot. But I am, and ultimately I decided I would write him into it as kind of a way to remember him, his way of speaking, his mannerisms. And there’s an intimacy about drawing. It’s not exactly him, but it’s kind of iconic. It represents him in a way that is easier for me in some ways than photographs. So I put him in there in sort of a reversal of fortunes. The little girl finds him after a natural disaster. She finds this little boy in the woods, and she reads his name tag inside out and she calls him Sito accidentally. Then they discover that that’s his name backwards, it’s actually Otis, but the situation is backwards. And she just keeps calling him Sito throughout the book. So, yeah, it’s sort of a monument to him. And my wife puts it this way: First it was a book for the kids I didn’t have, then it was a book for the kids I had, and then ultimately, too, it was a book for the kid that I lost. It’s all of that for me.

Miller: Jonathan Case, thank you so much for joining us, and congratulations on this truly lovely book. Thank you.

Case: Thank you for having me. I appreciate you having me on.

Miller: Jonathan Case is a cartoonist. His latest book is the graphic novel ‘Little Monarchs.’

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.