Editor’s note: This is the first story in an ongoing series about how Oregon officials managing groundwater supplies have fueled crises and inequities, leaving the state ill-prepared to meet the growing challenges of drought and climate change.

The warnings were hard to miss on a forsaken stretch of Highway 26 in Eastern Oregon. A sign reading “Travel at own risk” clung upside down to a weather-beaten post. A private driveway forewarned: “If you haven’t been invited into our ranches, you are not welcome.”

At the end of the road, a gray-haired man stepped out of a mobile home and frowned. Marv Farley was having a bad day, the kind with too much work and not enough help.

“We’re clearing everything out,” said the 67-year-old, who was in the process of packing up a sprawling cattle ranching business that’s been in his family for generations.

A sign warns people to travel at their own risk, as clouds cast shadows over the Cow Valley in far Eastern Oregon on Nov. 17, 2021.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

“I’m tired, I’m working 18 hours a day,” he said.

In November, Farley took a break to drive through the sagebrush of Malheur County’s Cow Valley and have one last look at a landmark from his childhood — a dry gully. He remembers it differently.

“There used to be water in this creek all year long. When me and my brother were little kids, we’d bring our fishing poles and catch little catfish,” he said.

The fish are long gone. Farley said the creek has been continuously dry for 18 years. Wells for home use and livestock have failed, too. The pumps had to be lowered to reach the only year-round water supply in the valley deep underground.

Farley and his older brother, Guss Young, sounded alarms to state regulators in 2015.

“We have creeks and springs drying up that have always had an abundance of water,” Young wrote in an August 2015 email to the Oregon Water Resources Department, the state agency in charge of managing water supplies. The brothers pointed at a farm across the highway, where monumental sprinklers called pivots use groundwater to turn the valley floor green with hay crops in spring and summer.

Today, out-of-state investors control the pivots, and the valley’s entire groundwater supply.

Situated about 40 miles from the nearest grocery store, and more than 300 miles from Portland, Cow Valley is not as much of an outlier as it seems. The 33 square-mile patch of Eastern Oregon is emblematic of how the Oregon Water Resources Department has long ignored sustainability concerns. More than six years after media reports and a state audit exposed the agency for failing to protect stable groundwater supplies across the state, policies and practices enabling overpumping have not substantially changed.

Rural communities have been first to bear the consequences, which are worsening under the stress of megadrought and climate change. Now, Oregon lawmakers are pouring more money than ever into a troubled bureaucracy, as agency leaders promise that more data and studies can lead to better water management.

‘Barren waste to productive fields’

Extraction of groundwater creates cones of depression. The deeper the well, the more powerfully it can divert water away from shallow connections.

Valentine Barker / Special to OPB

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates about 30% of all the freshwater on Earth exists underground. This unseen wealth of water comes largely from rain and snow saturating the dirt and percolating through rocks. From there, some of the groundwater makes its way back to the surface, evaporating from soil, or discharging through natural springs and coalescing into rivers and creeks. Without humans much of this water would remain stored underground, while the amount leaving would not exceed what mother nature recharges.

But as aquifers across Eastern Oregon now show, pumping by wells can erase eons of equilibrium in just a few years, endangering shallow connections to the surface.

Farming’s reign in the Cow Valley dates back to 1949, when a developer named Rankin Crow drilled the first irrigation well. The project soon transformed what had been sagebrush and cattle range to “a domain where green growing crops stretch to the horizon,” according to a 1950 article in The Malheur Enterprise. The newspaper cheered Crow for converting “a barren waste to productive fields.”

A cattle rancher and rodeo producer born at the turn of the last century, Crow’s autobiography describes how he traded rangeland to pay a well driller, then persuaded the Idaho Power Company to shoulder the cost of building a line capable of powering deep agricultural wells. The electricity would cost him, but the water itself was free for the taking.

Crow’s neighbors started sinking their own irrigation wells, which triggered a bitter legal fight over who had dibs on the valley’s quickly shrinking water table.

Rankin Crow, a former rodeo rider, is credited with conceiving of the deep-well project to bring water to Cow Valley. Aug. 13, 1950.

Courtesy of Oregon Historical Society Research Library

In 1959, the state engineer stepped in to declare Cow Valley as Oregon’s first ever critical groundwater area. The designation called for controls to protect “reasonably stable” groundwater levels, kicking off 60 years of monitoring and data available through the water resources department. In effect, the 1959 order enshrined one user’s dominance over the resource for generations to come. It banned future groundwater rights, but did not diminish existing claims — like those issued to Crow just a few years earlier.

Crow’s legacy in the valley continues through those claims. Under state law, Crow’s original water rights are permanently attached to this land. So, in 1978 when he died, his unsustainable wells lived on.

Now, Crow’s former empire literally glows on the horizon during spring and summer, as one neighbor remarked. Electric lights blaze from the pivots spraying water at night: “When you’re used to total darkness, it looks like you suddenly came across a Bi-Mart parking lot,” said Karen Oakes Ramer, a rancher who owns property about 10 miles away.

In 2019, Green Alpha II LLC acquired about 3,300 acres with Crow’s water rights for $8.1 million. The company is part of a vast network of entities controlled by Homestead Capital, a private equity firm based in San Francisco and founded by former directors from Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan. Corporate filings and property records show the Homestead firm controls more than 50 similarly-named companies with title to thousands of acres of farmland across the U.S.

“We like to find properties that have been under capitalized,” the firm’s website states.

Green Alpha’s Cow Valley farm manager Skye Root, who grew up in Harney County and is based in Boise, said the equity firm uses the land to grow seed potatoes, sugar beets, wheat and hay.

“We’re not in this to just dry something up. We are good stewards of the land,” Root said, adding that he is a third-party manager, and not authorized to speak on behalf of Homestead Capital.

Mullein stalks ring the edge of an irrigated field owned by Green Alpha, LLC in Malheur County's Cow Valley.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

Representatives at the firm did not respond to multiple requests for comment, which Root said were forwarded to him.

Last October, Green Alpha received final approval from the Oregon Water Resources Department to move water between the wells on its property. Root said the changes allow the farm to use less electricity and move water onto fields more efficiently.

“We are not taking more water out of the aquifer than others have for decades,” he said in an email. “With high efficiency sprinkler packages installed since purchasing the property, we are removing less groundwater than prior to purchase.”

Farley and his brother spent years challenging the company’s application to transfer water rights around, before reaching a settlement agreement in 2019. Farley said the family ended their protest because it was expensive to pay lawyers, and it seemed futile to challenge the state’s approval where groundwater problems were already so well-known.

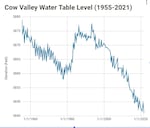

Oregon law since 1955 has called on regulators to maintain reasonably stable groundwater levels, but the valley’s water table has been shrinking farther and farther below the surface, dropping about 33 feet in Farley’s lifetime. About half of that decline has happened in the last 10 years alone.

“This is not reasonable,” Farley said. “This is abuse.”

Root disputed that claim, calling the valley’s groundwater “incredibly stable” compared to other parts of the West.

Part of Root’s assessment is likely based on water issues that have plagued Oregon’s Harney basin, where Root’s father, Andy Root, is a farmer and major well developer. Widespread groundwater declines there have put the region at risk of ecological and economic collapse. In one area, the water table is dropping as much as 10 feet every year due to irrigation pumping.

A satellite image shows green crop circles in an otherwise dry stretch of Eastern Oregon's Cow Valley.

2022 Microsoft Corporation, Earthstar Geographics SIO / OPB

State records suggest that once Cow Valley’s water table drops more than 32 feet total from pre-farming levels, it won’t naturally discharge to springs and creeks anymore. With a projected decline of more than 30 feet already, groundwater in the valley may soon be nearing a point of no return that will end surface connections. In 1959, Oregon’s water managers explicitly endorsed allowing this to happen to capture water deep underground for irrigators, calling any natural flow to springs and creeks “losses.”

“A large part of this groundwater, which is not now being put to beneficial use, could be utilized if the water table were lowered sufficiently to reduce these losses,” reads the 1959 order from the state engineer.

This strategy has not been updated, meaning more legal leverage for people with the deepest wells, likely death for groundwater dependent ecosystems, and financial ruin for people who can’t afford to race to the bottom of aquifers.

“If an aquifer were to have no connection to surface water, the Department currently has no legal mechanism to protect groundwater ecological values,” OWRD deputy director Racquel Rancier wrote in response to OPB’s questions.

She said that in an effort to prioritize limited resources, the department is “focused on other areas of the state that are experiencing more rapid and widespread groundwater level declines.”

‘A crisis in slow motion’

In the midst of megadrought that is breaking 1,200 year-old records, nearly every community in Oregon is abnormally dry, and the U.S. Drought Monitor finds two-thirds of the state is experiencing severe drought conditions this year.

As the irrigation season for 2022 begins, most rivers and reservoirs already can’t deliver on the promises of existing water rights. Shriveling snowpack and drier summers are also causing groundwater depletion, which threatens the ability of existing water supply infrastructure to meet growing demand across Oregon, according to a 2021 report by Oregon State University’s Climate Research Institute.

Oregon Department of Water Resources data show groundwater declines worsening in the state's first critical groundwater area.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

Meanwhile, the water resources department has a track record of enabling crises. A 2016 investigation by the Oregonian/OregonLive revealed how water rights managers approved more wells than aquifers can reliably sustain across approximately one quarter of Eastern Oregon. Following those reports, state auditors found the agency lacked planning and decision-makers were not efficiently using existing data.

“Some of this data have not been analyzed or made available across the agency to help make informed permitting and water rights decisions,” auditors wrote, directing regulators to focus on protecting groundwater supplies and “integrating sustainability considerations into water management decisions.”

Six years later, key policies contributing to the overpumping of aquifers east of the Cascades have not substantially changed. Statewide, water rights managers continue to approve new wells without knowing whether enough water is available. Residents and businesses with failing wells are told to dig deeper, and most are left to foot the bill. Wealthy interests are able to overturn water right denials by negotiating behind closed doors.

One thing is different now: Last year, lawmakers approved a historic public spending package on water, with some $538 million for projects statewide, and much of it passing through the water resources department.

Representatives leading the House water committee championed bills to secure the funding, including a Republican who operates hay farms in Harney County, Rep. Mark Owens.

“The first conversation that you’ll get from the [water resources] department when you ask them about different questions is that they can’t address that; they’re understaffed or underfunded,” Owens said.

He hopes shoring up the agency’s budget through 2023 will empower its leaders to base decisions on science, and to say no to new groundwater permits unless scientific evidence shows water is available.

Republican Oregon state Rep. Mark Owens tours one of his company's hay fields in Harney County on Aug. 27, 2021.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

The crisis in his home county sparked a moratorium on new water rights in 2015, as the water department and the U.S. Geological Survey launched an in-depth study of the local aquifers. Owens said he supports funding for more basin studies because he believes the problems are widespread.

“If you’re not having a water issue in your basin, hang on. It’s coming,” he said. “We need to put on the brakes throughout the whole state on allocating water.”

To shepherd the water package through the Legislature in 2021, Owens worked closely with a Democrat from the other side of the state, Rep. Ken Helm of Washington County.

At a December presentation to the water department’s public oversight board, Helm pointed to climate data as another driving force for reform.

“We just will not have a choice,” Helm said, “It’s a crisis in slow motion.”

OWRD leadership

Policies of the Oregon Water Resources Department don’t directly address climate change, according to agency director Tom Byler.

“Our state water laws were born out of concepts that were put into place in the 19th century,” he said in a September interview. “The whole idea setting up the system of laws around the use of water is for people to use water.”

Oregon Water Resources Department Director Tom Byler tours a Harney County hay field on Aug. 27, 2021.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

A lawyer by training, Byler said he worked on policy with the department from 1995 to 2001. After that, he served as an advisor to two former Democratic governors, Ted Kulongoski and John Kitzhaber. Byler then spent nearly a decade as executive director of the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, before Kitzhaber appointed him to the state’s top water job in 2014.

Byler said some strides were made after the damning 2016 audit, such as a groundwater study of the Harney Basin. The department imposed rules to prevent new water rights in much of Harney County, as well as in Northeastern Oregon’s Walla Walla basin.

“We also have made progress in our data management,” Byler said. “The story that we’re trying to tell is that we need to be cautious about groundwater going forward.”

But some staff who have worked under Byler believe special interests wield outsized influence over decisions, and that leaders within the agency disregard scientific evidence to avoid legal challenges from wealthy developers.

Last year, OPB emailed a survey to 188 current and former department employees, asking them to evaluate the agency’s effectiveness at its stated mission and values. Though only 20 people responded, some clear themes emerged among that group. More than a dozen interviews with current and former staff echoed similar concerns.

Until recently, the department employed only one full-time employee devoted to planning. Harmony Burright said she feels very few people in the state are involved in deciding who gets to use water.

“I’m worried that communities may be left to deal with the resulting conflict and crises, and the public may be left to foot the bill for what could have been an avoidable problem,” Burright told OPB. She left the department last October to work as an aide for Owens.

Other former and current employees who spoke to OPB asked to remain anonymous, all citing fears that airing criticism would damage their careers in state government agencies.

Two former staffers who requested anonymity said they quit the water resources department after becoming disillusioned by pressure to support questionable water rights decisions.

Irrigation equipment and cattle frame views of Eastern Oregon near Ironside in Malheur County on Nov. 17, 2021.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

A former natural resource specialist who left in 2018 said in a phone interview that her concerns about missing or outdated technical information would often be dismissed after her manager brought them to a high-ranking division administrator, Dwight French.

“I was just told to go ahead and get the certificates ready for signature and issuance,” she said in a phone interview. “I felt that there was a lot that went out the door that was a mess.”

French has been a fixture at the department since 1991, and has been involved in individual water rights decisions since 1994. He was promoted to division administrator in 2005.

In 2018, a water rights caseworker named Barbara Poage complained about French to the Bureau of Labor and Industries, alleging sex-based and whistleblower discrimination. A BOLI investigation did not find substantial evidence of discrimination, and dismissed the allegations. However, the inquiry did suggest that “French’s leadership may be problematic,” BOLI investigator Jessica Smith noted in her report. Smith interviewed one of Poage’s coworkers, Patricia McCarty, an attorney who is the department’s longtime water rights protest coordinator. According to Smith’s notes, McCarty described French as “defensive and reactive, and an authoritative type person.”

“I have to handle him very carefully and make sure he doesn’t feel like he’s being opposed or questioned, or that he doesn’t feel like I won’t carry out his wishes,” McCarty reportedly told the investigator in 2018. “He really doesn’t like to have women be... well, he doesn’t like being challenged. He won’t tolerate it. I’ve seen him go after some people… He goes after somebody and gets them fired. I watched him do that.”

A department spokesperson, Alyssa Rash, said the agency had not received any formal complaints against French.

In an email to OPB, McCarty distanced herself from the complaint.

“The situation described is confined to the rare circumstance when a staff member is arguing with [French] and the conversation has turned overtly hostile,” McCarty wrote.

McCarty said she had personally witnessed “only a handful” of heated exchanges between French and other OWRD employees in her more than 14 years at the department.

“No part of my conversation with the investigator had to do with how Dwight or any other manager makes decisions on water rights decisions. Nor did the conversation include opinions or statements on Dwight’s professional competence. Statue, rule, guidance and policy make decisions on water rights. If for some reason, a particular application falls outside of these sideboards, that is the circumstance in which a water rights decision is made by management using data and recommendations from our scientists,” she said.

French provided an emailed statement through the department’s spokesperson, and declined to comment on the BOLI investigation.

“In regards to water rights decision-making, I will say that I strive to foster an environment where people can disagree and feel that they can voice their opinions,” French wrote.

“As an agency, OWRD encourages staff to voice their concerns, and in some cases folks have taken those opinions or concerns to the director. When we hear concerns, there may be resulting changes in agency practices and policies; and sometimes after taking those opinions under consideration, we decide to proceed with the plan we’d previously identified as we must make decisions based on our understanding and application of the law,” French said in the email.

Burright, the planner who resigned from the agency last year, said she felt leaders were not likely to engage with feedback from staff, while being very reactive to the demands of outside interests, such as lawyers, lobbyists and lawmakers.

“I believe this leads to poor decision-making and a deep sense of disillusionment within the ranks and within the communities we serve,” she said.

Industry access

An analysis of director Byler’s calendar gives some insights into influence at the department. Over the first nine months of 2021, four lobbyists representing agricultural users secured about 50 meetings with Byler, many of them one-on-one. His office scheduled time with lobbyists for agricultural water users about three times more often than with advocates for conservation groups. Byler met with a nursery industry leader, Jeff Stone, more than a dozen times over the nine months. Stone is the executive director for the Oregon Association of Nurseries, a trade group for the state’s largest agricultural sector.

“I actually thought I would have had more meetings,” Stone said in an interview.

He said he works closely with Byler and the water department to find compromises with other groups and avoid legal battles over policies and new laws.

“At the end of the day, it’s going to be a political settlement, or end in a lawsuit,” he said.

Under Stone’s leadership the Oregon Association of Nurseries has staunchly opposed bills to require water rights holders to measure and report how much water they use. Supporters of measurement and reporting say it’s foundational to sound water management, and for identifying bad actors. Stone believes the requirements would fuel paranoia about the true intent of state data collection, and conflict between neighbors. Because water rights must be used at least every five years to stay valid, Stone worries that growers who embrace efficiency practices and use less water could then be forced to forfeit part of their unused water rights.

Clouds throw shadows on the hills behind an irrigation pivot in the Cow Valley critical groundwater area in November 2021. In a 2015 email to the Oregon Water Resources Department, cattle rancher Marv Farley and his brother Guss Young wrote, “We have creeks and springs drying up that have always had an abundance of water.”

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

“We just don’t trust the government,” Stone said. “I don’t mind the department using all this data on something that is a cogent policy, but right now, all I see is data being collected and nothing’s happening with it.”

Byler hesitated to say if the department has an obligation to prevent the creation of more water rights than supplies can support.

“I believe that part of our responsibility is to manage the resource effectively, and that’s part of our considerations,” he said. “The reality that we face is that decisions have been made by the water resources department over many decades.”

In September, he pointed to outdated laws, rather than issues with how his agency interprets them and makes rules. However, recently the water department has signaled it plans to modernize groundwater policies, and redefine how it approaches critical groundwater areas.

Just a week before his interview with OPB, Byler’s calendar shows he met with advisors to discuss one company’s control over the state’s first critical groundwater area in the Cow Valley.

When asked about the longstanding, 1955 law calling for Oregon to determine and maintain “reasonably stable” groundwater levels, Byler said the department decides what that means on a case-by-case basis, largely by consulting local water users.

He then posed a scenario strikingly similar to the real situation in Malheur County’s Cow Valley.

“For example, if you had one user on an aquifer, and there were no ecological values to be protected on that groundwater system. What would reasonably stable mean?” Byler asked. “Would we stop them from using the water at some point if no one else is using it?”

When OPB later followed up to press for an answer to the question, Byler’s office declined “to speculate on hypothetical scenarios.”

Having an ‘edge’ in Cow Valley

When Texan billionaires asked for water rights on the edge of the Cow Valley critical groundwater area in 2015, nobody stood in their way.

Dan and Farris Wilks of Cisco, Texas, are brothers and fracking magnates who collect ranch properties across the West. Considered one of the country’s largest landowners, their families are also known for financing religious conservative political causes and climate change denial. They heavily backed Texas Sen. Ted Cruz’ 2016 presidential campaign, according to Reuters.

In 2016, Oregon regulators with OWRD approved a permit allowing the Wilkses to plunge an irrigation well less than 1,000 feet from a critical groundwater area boundary. A state review of the plan even justified water availability with false information.

“Groundwater levels have rebounded markedly in the adjacent Cow Valley Critical Groundwater Area as a result of changes in irrigation practices and the groundwater control provisions,” the review completed in August 2015 falsely states, citing decades-old data.

The head of a Green Alpha LLC well, which plunges more than 400 feet underground into a volcanic aquifer.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

In fact, groundwater declines had worsened. While the Wilks application was under consideration, Cow Valley rancher Farley and his brother sent their complaints about failing stock and domestic wells to the department. A state hydrogeologist promptly responded in April 2015, showing the department had up-to-date data on hand.

“It appears the water levels have been in a steady decline for the past couple of decades out there. Some of this change could be climate related, but this will take some more digging,” Phillip Marcy wrote back to the ranchers.

Still, less than a year later, the department gave final approval for the billionaires’ well, backed by the inaccurate groundwater review.

“We believe that a mistake was made in that review,” OWRD deputy director Rancier wrote in response to questions by OPB. “The proper groundwater levels will be taken into account for any further action required on this permit in the future.”

Today, the Wilks’ Cow Valley wellhead is visible from the highway. It appears abandoned. A representative for the Wilks brothers declined to comment.

In 2017, the Wilkses succeeded in getting permits for other wells near the Cow Valley, in the nearby community of Ironside, Oregon. Studies available since the 1970s indicate the area’s aquifers may only support a handful of wells, and that the “development of further permanent groundwater rights in the volcanic aquifer should be approached with caution,” state records show.

The department initially signaled it would deny the Wilks’ applications, finding both of the requests were “not within the capacity of the groundwater resource,” and that one would likely interfere with existing wells. But then, the state reversed course. It allowed both wells. For the one deemed likely to hurt a neighbor’s water right, the Wilks agreed to reduce the requested flow.

Ironside rancher Karen Oakes Ramer was caught off guard by that approval.

Karen Ramer tries to lure a horse with grain as a llama keeps watch on the doings at the Oakes Ranch near Ironside, Ore., on Nov. 16, 2021.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

“[The water department] said that they were going to deny it,” she said. “The next thing we knew it was approved, but it was after the fact that we were told, not while we could still complain.”

The development impacted an artesian well that heats her parents’ home. Its 96 degree water used to flow unaided from a hole in the ground, much like a spring, but at the start of this winter she needed an electric pump to bring the water to the surface. Since her family’s well was drilled in the early 1950s, its flow has declined by as much as 75%, likely due to groundwater declines, the water department noted in a review before it allowed a new and wealthy neighbor to tap into the same source in 2017.

Over the years Ramer said she has lowered other pumps as more neighbors use groundwater. This costs thousands of dollars on top of the recurring expenses for electricity.

“The [irrigation] wells will cost $2,000 and up a month to pump per well. And one might just irrigate 70 acres,” Ramer said.

Her family makes a living from raising cattle, leasing pasture, and growing some hay crops for livestock feed. All of it depends on water, and the dry years are starting to show.

“Our cows came in the worst I’ve seen them in my lifetime,” Ramer said in November.

A doctrine common across Western water laws is prior appropriation, which means that when water is scarce, the people with the oldest rights take priority. Ramer’s family would seem likely winners in this system, which many people refer to as “first in time, first in right.” Ramer’s family surface water rights dating back to her great-grandparents’ arrival in Malheur County. One claim is from 1871, others were staked in the 1880s, she said.

A plaque in the hallway of Karen Ramer's family home celebrates the family's long tenure in Eastern Oregon.

Emily Cureton Cook / OPB

But with drought, climate change and more demand for water, even these senior surface water rights are short straws. Last year, Ramer estimated their ranch near Ironside got about half the amount of promised creek water. More and more of her neighbors are relying on wells, she said.

“You’re happy to see the valley turn greener and be more productive, but it also scares you… You don’t want the water table to just keep dropping and dropping, and then nobody can use it.”

Still, she’s hesitant to condemn anyone.

“Whether it’s money, or whether it’s knowledge, or being really handy with something, you have to have an edge out here,” she said. “And if you have money, you don’t have to be as careful.”

Farley, the rancher who tried to get the water department’s attention for years, sold his family’s Cow Valley property last year. He wouldn’t talk about the buyer because he said he signed a non-disclosure agreement. A county record of the transaction shows the ranch’s new owner is a company controlled by a Hong Kong-based private equity firm.

Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify how Green Alpha II uses water on its property in Cow Valley.