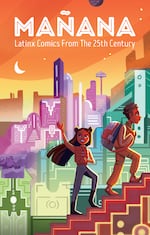

"MAÑANA: Latinx Comics From The 25th Century." Published by Power & Magic Press

Joamette Gil

Power and Magic Press is an award-winning independent comics publisher in Portland. In early 2022, the company published “MAÑANA: Latinx Comics From The 25th Century.” The collection features 27 young adult stories by creators all across the United States and Latin America. We talk to Joamette Gil, who founded the Power and Magic Press, about futurism in Latinx comics, her experience editing the anthology, and more.

This transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB, I’m Dave Miller. Power and Magic Press is an award winning independent comics publisher in Portland. The company recently put out a new science fiction collection in Spanish and in English called Manana: Latinx Comics from the 25th Century. It features 27 stories for young adults by artists and writers from across the US and Latin America. Joamette Gil founded The Power and Magic Press and edited the new collection and joins us now. Joamette, welcome to Think Out Loud.

Joamette Gil: Thank you so much for having me.

Miller: What was your starting point for this collection, when you started asking for submissions?

Gil: I started asking for submissions around the time that the Trump administration started ramping up family separation at the border, actually. It had been weighing on me a lot, obviously, I’m Latinx, myself, and something else that was sort of in the zeitgeist at the time was the latest Star Wars trilogy. And at least amongst my community, part of our discourse was sort of how great it is to see Oscar Isaac playing Poe Dameron, who ended up becoming a major character, and sort of seeing Latinx representation in one of the biggest media franchises in the world and sort of that dichotomy between seeing ourselves represented in media and how Latinx people were actually being treated in our country, just just didn’t sit well with me. It was weighing on my heart and a lot of what we put out there, Power and Magic Press ends up coming out of me taking a look at the world, and thinking what do I want to see more of? Or what’s a topic that I want to hear a marginalized community talk about where I want them to explore this space. So it seemed like a good time to put out our first science fiction collection since our futures were feeling so incredibly uncertain.

Miller: Oh, I was wondering, so I was thinking why science fiction in particular, what was the connection for you?

Gil: Right. So, I talked about this a little more in depth in the introduction to our book, but science fiction is a very active form of fiction. It’s playful, in the way that fantasy is, it’s exploratory but it’s also, it’s concrete in the sense that you’re taking things that are applicable to your day to day life or how you imagine your real context changing or shifting in the future. And it’s sort of a common knowledge that a lot of real world technologies have been inspired by just ideas that someone put into science fiction, whether because they were tuned in to what was being researched at the time, or they just happened to have that idea come to them from their own imagination. People read those stories and it impacts sort of like what occurs to companies, to actually develop after the fact. And I thought it would be really powerful to have more science fiction that looks at current problems and potential solutions, but specifically from the point of view of people who are normally not solicited for their opinion regarding the future.

Miller: What were the themes that started to emerge when you sifted through the submissions?

Gil: One of the biggest themes actually, which relates back to your previous segment, was climate change. The stories cover a lot of tones, some are a little more melancholy with a glimpse of hope at the end, some are more playful. But something that emerged throughout, was that Earth’s future is bleak. [Laughing] There’re so many stories that deal with the rising sea levels,...

Miller: including one that you wrote yourself.

Gil: Yeah

Miller: But there are others as well, and about food insecurity and how one of the characters has never eaten an apple before and it becomes a sort of sweet part of a love story. But I wonder if you could tell us about the comic that you wrote for this collection called ‘Miami Story.’

Gil: Sure, it was written by me and illustrated by Ashanti Fortune, who’s an Afro-Mexican Cartoonist. It’s sort of a…not a eulogy, but like a postmortem. It’s kind of taking for granted that sea levels will rise to the point that Miami Florida will completely be underwater much sooner than the 500 years in the future that the story takes place. So the premise of the story is that the city of Miami is no longer on ground – Florida has long since sunk deep beneath the sea and Miami is now contained within a mega structure that stretches from the ocean floor to the stratosphere. Our main character works in a labor division located near the stratosphere level working sort of as a NASA employee, and she’s never seen the ocean before, not up close, like she’s peered through the clouds, through the windows on clear days and knows that there’s a wide expanse of water beneath her, but she’s never actually visited it, she’s never touched the sea. And it’s about the first time that she gets clearance, as someone with no usual business to having clearance, to the lower levels to go down there. And on the way you see hints of how society has been stratified. So it’s a little bit of the same old same old in some ways there’s class divisions, there’s places you get to live based on where you work, etcetera. But it centers on her inner emotional reaction to something as simple as getting to see the ocean and how in her mind, as a Cuban-American person though, it’s unclear whether ‘American’ as a category even exists anymore, is tied less to the history of the Cuban diaspora in Miami or less to the island of Cuba itself, which we’re also left to wonder, is Cuba underwater, does Cuba still exist? Her sense of self and identity and knowing that she’s Cuban based on history is…it’s based on a connection to the sea. And that’s sort of related to my personal feelings about being Cuban-American and the child of immigrants who grew up in Miami, Florida. Once your identity is based in one generation, was from this place, and now this generation is in a second place. The tension between, ‘am I from here, am I from there, which location is more a part of who I am?’ It becomes more clear to me, to have your sense of identity based on movement, and the sea is sort of this liminal space. I like to deal with liminal spaces a lot, it’s not just its own world, but it’s also a place of transition. You sail from Cuba to Miami or from Miami to Cuba. The ocean transports you and rather than sort of dwelling on ‘oh, Miami’s gone or Miami will be gone once it sinks sinks beneath the sea’ or ‘I’ve never been to Cuba and that’s part of my legacy’ sort of giving the spotlight to how we hold on to who we are, as the world changes, as the climate transforms locations and nations and places of heritage, once the the dirt that is your identity isn’t there, and you can’t touch it, the mode of moving through the world, of traveling, of transitioning the ocean can become our new identity.

Miller: There’s another kind of change that you explore in other stories. The triumph of Latin American cultures in various ways, whether that means that Puerto Rico is the technological center of the world in one story or in another, San Diego is a nuclear wasteland and Tijuana is a gleaming city. What does it mean to you to read these stories?

Gil: It more than gives me hope because I don’t have any particular personal hope for any given place on earth to become the new, like, center of culture or the pole of power or anything like that. We’re kind of seeing the effects of living in a uni-polar, like, it’s a bipolar political world right now. So for me, it just sort of serves as a reminder that history is very, very long and that we take a lot of things for granted now, like we take certain groups of people being in power for granted. We take certain people being oppressed for granted. And we can feel like how much power we have now, defines who we are when it defines our experiences, but I don’t think it defines our identities, just as like the Aztec empire was one of the most impressive civilizations on the globe at one point, only to be reduced to rubble by Spanish Conquistadores. One day the US won’t be what it is now. The state of the US as the dominant global power isn’t something we can take for granted forever and whatever power replaces the US, the US’s role subsequently, they won’t be in power forever. So having locations that we’ve never considered as poles of power in various ones of these stories to me just sort of serves as a reminder that power is fluid, history is long. Sometimes it starts towards justice and sometimes it arcs towards injustice and you never really know what’s going to happen. So nothing is set in stone. We’re the makers of our own destinies.

Miller: Gil, thanks very much for your time today.

Gil: Thank you so much.

Miller: Jo Gil is a Cartoonist and Editor of Power and Magic Press, the publisher of the new series, the new collection, Manana. Tomorrow on the show, the pandemic shined a bright light on the digital divide in Portland and across the country. We’re going to hear how a nonprofit and the city of Portland have responded to the digital access gap. Thanks very much for tuning in to Think Out Loud on OPB and KLCC. I’m Dave Miller, we’ll be back tomorrow.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.