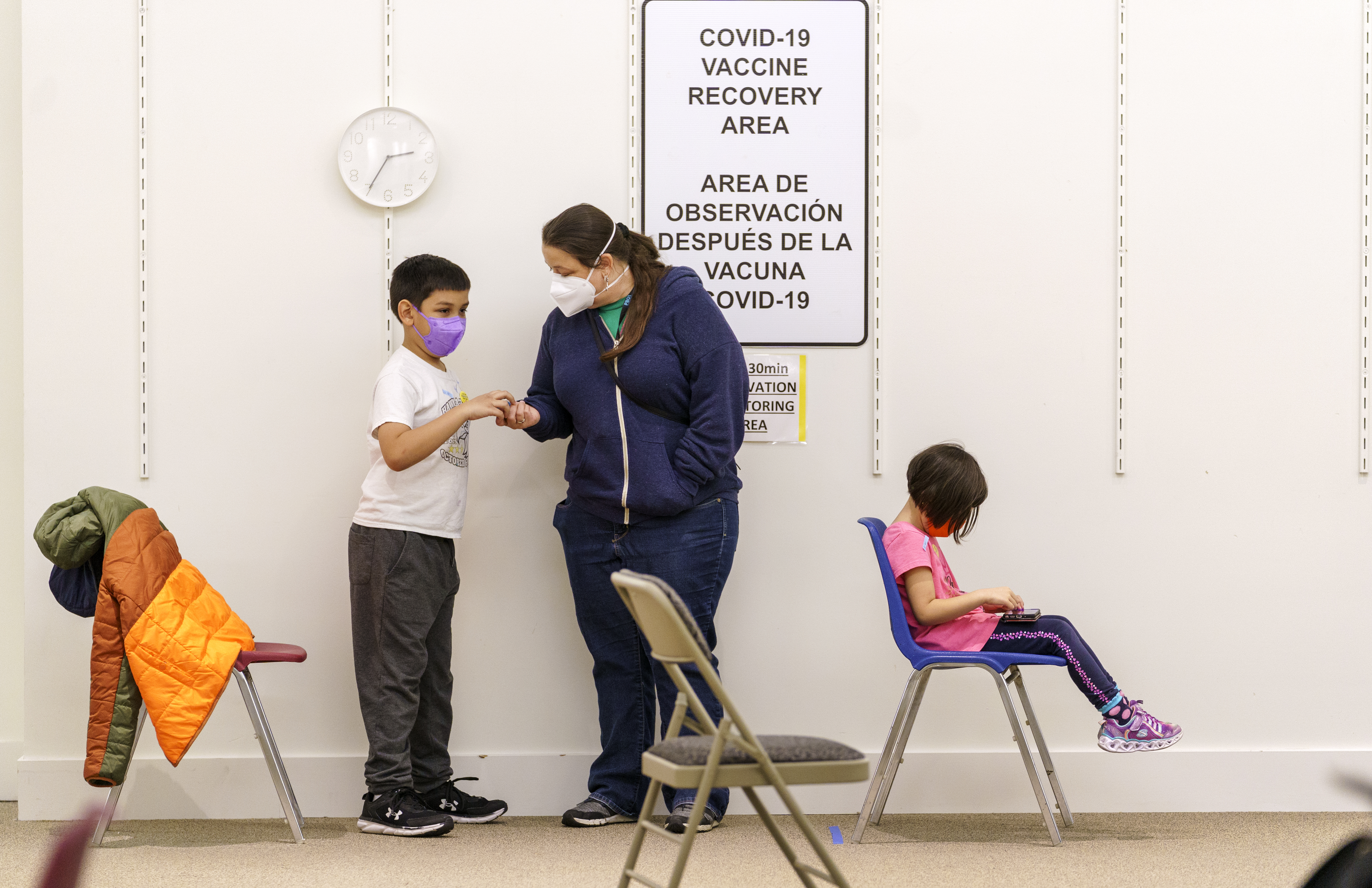

An OPB file photo from a November 2021 pediatric COVID-19 vaccine clinic at Clackamas Town Center. Oregon is the only state does not provide full coverage for every child under Medicaid.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

Federal law requires state Medicaid programs to cover medically necessary, physical, dental and behavioral expenses for children, but there’s one state that has an exemption: Oregon. Since the 1990s, Oregon has applied for federal waivers to ignore the “cover all children” rule. The Oregon Health Authority argues this is necessary in order to make more Oregonians eligible for Medicaid programs. But, as the state awaits approval to renew its latest waiver, advocates and parents want change. Ben Botkin is a reporter for The Lund Report. He joins us to share his latest story on why some kids in Oregon can’t get the care they need.

The following transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer:

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. For decades now, Oregon has gone its own way when it comes to its approach to health care for low income kids, it is the only state in the country that’s chosen to not cover every medical procedure that’s considered necessary for children who qualify for Medicaid. Those are kids who have the Oregon Health Plan. That’s because Oregon has been granted a series of federal waivers once every five years since the mid 1990s. But as the state awaits a renewal of that waiver, advocates and parents are once again calling for change. They say Oregon’s system is unfair, illegal and even racist. Ben Botkin wrote about this recently for The Lund Report. He joins us with more. Ben Botkin, welcome to Think Out Loud.

Ben Botkin: Thank you.

Miller: To understand what Oregon is doing differently than every other state, we actually have to start with a little bit of history. Can you explain what federal law mandates, going back to 1967 for children who qualify for Medicaid?

Botkin: Sure, absolutely. So in 1967, this is under the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, Congress passes a law with a long name. It’s called ‘The Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment Program.’ And what that basically means is all Medicaid children get regular checkups, dental, vision, physical checkups. But beyond that, that law requires all states to provide all children on Medicaid, up to age 21, any medically necessary care. And the key point to remember with this is any medically necessary care, even if it’s something that Medicaid would not provide an adult.

Miller: Oh, because this is specific to children. There’s no provision like this for adults, only for children under federal law?

Botkin: Correct. This particular law is specifically aimed at the quality of healthcare for children on Medicaid, basically with the idea of children with certain needs and have to be set up for a successful adulthood.

Miller: So that went into effect when the Medicaid program was created back in 1967. Now, we can fast forward to 1993 when Oregon made some big changes to its Medicaid program, known as the Oregon Health Plan. What were those changes?

Botkin: So In the 1990s, Oregon’s goal was they wanted to get more people on Medicaid, a wider segment of the population. Now, as part of that, they recognized, okay, we still have certain funding limitations. So the goal was... Oregon drew up a list of what’s called a prioritized list of services. So basically it ranks the importance of all medical treatments. Everything from prenatal care to organ transplants. And every year, the state sets a number on that list of what will be covered and what will not be covered. So when Oregon started its Medicaid waiver application in the 1990s for the first time, It required a waiver from the 1967 law. And what that waiver basically did was it said yes, we will provide medically necessary care to Medicaid children, but that care will be restricted based on Oregon’s prioritized list of services of what’s covered and what’s not covered.

Miller: And the feds said, ‘yes.’ But just so we’re all clear on this, Oregon made this policy decision to offer more basic, maybe more preventative, certainly more more basic services to a higher number of residents as opposed to more comprehensive care to a smaller number?

Botkin: Yes.

Miller: Has that worked in practice? I mean, does Oregon provide Medicaid coverage for a higher percentage of children or adults than other states?

Botkin: I would say yes. As far as the number of people covered, Oregon is definitely on the cutting edge. Like if you look at, say back in 2018 Oregon passed ‘Cover All Kids,’ which puts undocumented children on Medicaid. So on the one hand, Oregon’s definitely doing things that other states are not doing like cover all kids. But on the other hand, you still have this underlying issue, which is certain things that fall below the line of coverage are being denied for kids.

Miller: How does the state determine where different kinds of services fall in that list? In other words, how do they determine what’s going to be covered and what’s not?

Botkin: Right. It gets a little complicated, but the Oregon Health Authority has a Health Evidence Review Commission and that’s 13 people, appointed volunteers. They include a mix of medical providers and consumer advocates and they look at the scientific evidence of treatments as well as other factors like the needs and they then assign them to a certain number on the list. Now after each treatment and condition is assigned, it can be moved from year to year. So if technology improves for a certain type of treatment, it can get higher up on the list. so it’s certainly not set in stone and it’s something that changes every year, particularly as new treatments come on on the scene. So that’s a little bit about how that works.

Miller: Let’s turn to what this has meant for actual families. You talked to one in southern Oregon. The Molders, Can you explain what this list means for their lives and in particular a young man named Canaan Molder?

Botkin: Sure. So this young man, he has a rare genetic condition and it’s something that can affect your bone density and growth and it can also affect your hormones and cognitive abilities, things like your ability to concentrate. Now from the time he was two, until the time he became a teenager, he received Medicaid coverage for growth hormones which out of pocket, these would cost around $20,000 a year. Now his pediatricians at OHSU, some of the best pediatricians in the country, actually OHSU acknowledged this, has said, hey, he needs these growth hormones, his Coordinated Care Organization within the last year or so has said, well your condition now falls below the line for coverage. So we’re not going to pay for it.

Miller: And just to remind folks that the Coordinated Care Organization – that is the umbrella group that manages the Medicaid program for the state. And so they’re the ones

Botkin: Correct.

Miller: …who would say, ‘we looked at the list and it’s not on the list, it’s below the line. So we’re not going to cover it,’

Botkin: Right. So, like for example anything number one through 471 is covered, and this was somewhere in the neighborhood of 662. So they say, ‘Oh, you’re not covered.’ The doctors have been trying to negotiate and get it covered and made five other attempts over the last year and it keeps being denied. So this is a textbook example of a family with a kid with a condition will find their service automatically denied. Not based on what the doctor says is needed, but based simply on where this medical treatment is ranked on a numbered list of health services.

Miller: What has not getting this particular therapy over the last year and a half meant for Canaan Molder?

Botkin: So in his case, it’s more difficult for him to concentrate and do things like volunteer at the museum or work on schoolwork. It’s also meant that his doctor has had to find three different types of medication to put him on that don’t work as well, but are covered. So in this case it can create a combination of issues.

Miller: The Oregon Health Authority argues that these are not blanket denials. They don’t just say ‘no, you can’t have this coverage,’ because families can appeal them. How do appeals work?

Botkin: Well, in a couple of possible ways. You can ask your Coordinated Care Organization [CCO], that’s the Medicaid insurer. You can say, ‘hey, even though you’re not required to cover this, can you still do it anyway?’ So that’s one option. The other option would be to appeal directly to the Oregon Health Authority for a ruling for coverage. Now, these are all avenues. The issue though, that I hear is yes, these can sometimes work. However, this does create red tape that families have to navigate. while health care is being delayed.

Miller: We got a comment from Nina Vasquez on our Facebook page who wrote this, ‘I experienced this when my teenage daughter was denied, even after an appeal, foot surgery for some seriously painful bunions. She was not able to participate in school sports because of the pain. She recently turned 18 and hoped to someday have decent insurance. So she can have the surgery and have the opportunity to do things she hasn’t been able to do for the last several years.’ What are the other kinds of, what are examples of some of the other services that you heard about that might be denied?

Botkin: Sure. So, some are rare and some are pretty common. There’s rare things like developmental conditions that are connected to epilepsy for example. But on the more common side, hay fever medication that’s the best for a child can be denied. A pediatrician at OHSU told me that medications that do not make a child drowsy are not covered. However, medication that does make a child drowsy is covered. So that’s an example of a family has to decide, ‘Okay, will I accept a substandard medication for my child’s hay fever and set them up for difficulty in school with being tired or do I just let it go?’ So those are a few examples.

Miller: What did you hear from doctors or other health care professionals about the effects of this state policy?

Botkin: Well, a couple of things, I mean, the general sense I get is, as one pediatrician put it is, quote, ‘We shouldn’t have to be playing defense.’ In other words, they’re trying to get the best care for children. However, this is a bureaucratic problem sometimes that families and providers are forced to navigate. So this can mean things like, maybe a care is denied and the family gives up or a pediatrician will tell a family, ‘Hey, this care this treatment is going to be automatically denied,’ so it’s not even pursued. So it creates a situation where you can have a variety of different outcomes and not necessarily ideal ones.

Miller: You note that two doctors from Doernbecher Children’s Hospital wrote a letter to the state saying that its waiver is a fundamentally racist policy. What is their argument?

Botkin: So the idea behind that was you have more children of color and more minorities on Medicaid overall than on commercial insurance plans. So in a sense, you have children disenfranchised because care that they have a right to can potentially be denied. So there’s an equity question here and an equity problem that a lot of advocates see.

Miller: Meanwhile, the state is currently asking federal regulators to let it continue this policy. What’s the argument they’re putting forward as to why they should be allowed to do so?

Botkin: Oh, well there’s a couple arguments. One is that this process is more transparent because you have a list that’s public where you can look and see what’s covered and what’s not covered. They can also argue that you can advocate to get a condition or treatment moved up higher on the list. And finally, you have just the general sentiment of, well, there’s avenues where a family can appeal or ask their CCO – Coordinated Care Organization to cover it.

Miller: Let’s say that the advocates who say Oregon should should scrap this system that they were to win, either because the state decided to stop pursuing this ‘only in Oregon policy’ or if federal regulators said no, you have to stop doing this, that we’ve decided that doesn’t comply with federal law in a way that we don’t want to allow. But I mean, meaning that Oregon then would cover all care deemed medically necessary for children on the Oregon Health Plan, but if no more money went into the system, would that by definition mean that some Oregon children would actually be kicked off of the Oregon health plan?

Botkin: Not necessarily, because you’re still required by law to cover them. If they meet certain income requirements, I would say one thing to keep in mind is that the concern of advocates is that a medical treatment based on its number on the prioritized list will lead to an automatic denial before there is a discussion between Medicaid and the family and the provider of whether this is medically necessary.

Miller: Ben Botkin, Thanks for your time today. I appreciate it.

Botkin: Thank you.

Miller: That’s Ben Botkin, the Senior Reporter for the Lund Report.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.