Works by artist Ka'ila Farrell-Smith in "MESH" exhibit at Portland Art Museum.

Portland Art Museum / OPB

Visual artist, writer and activist Ka’ila Farrell-Smith says she considers herself a wartime artist.

Artist Ka'ila Farrell-Smith

Portland Art Museum / OPB

She is a member of the Klamath tribes and lives in Modoc Point, Oregon. When asked about how history influences her work, the answer weaves through over 150 years of white colonization and Indigenous struggles in the West:

She brings up the Modoc War of 1862, when Modoc war leaders resisted U.S. government forces for seven months in Southeastern Oregon and Northern California. She references the 1954 Termination Act, when the federal government terminated recognition of the Klamath Tribes. She speaks of the Native American boarding schools her father Alfred Leo Smith attended, and his advocacy that led to the signing of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act Amendments of 1994 .

Related: Related video: Contemporary artist Ka'ila Farrell-Smith

Farrell-Smith is one of four contemporary Indigenous artists featured in the new show MESH at the Portland Art Museum. Her works in the exhibition are a part of a series of 27 paintings called Land Back, named after the contemporary movement advocating for Indigenous sovereignty.

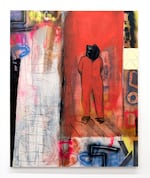

"Torture State" by Ka'ila Farrell-Smith, 2021

Portland Art Museum / OPB

“Land Back is very much a personal journey of healing through historical traumas from colonization that resonate throughout my family, my community, and through my mental and physical body,” Farrel-Smith said. “For me, the painting process is a personal healing process.”

In the paintings, those historical traumas are both communicated emotionally, through abstract forms and bold colors, and through words and images. In the painting titled Torture State, she depicts a figure in an orange jumpsuit and black hood, evoking prisoners of the War on Terror.

“The U. S. government lynched four Modoc war leaders, and my Great Grandmother, Emma Ball was nine years old and was forced to watch this,” Farrell-Smith said. “During the Bush and Cheney administration, their lawyer John C. Yoo cited the hanging of the Modoc war leaders as legal precedent to create the 2003 torture program, which led to the opening of Guantanamo Bay.”

Art and artists that need to be seen

Portland Art Museum Native American Art Curator Kathleen Ash-Milby said this intensity is what attracted her to Farrell-Smith’s work

“They’re not joyous paintings, necessarily,” Ash-Milby said “The subjects are very heavy, but they’re also beautiful. I think that that combination of beauty and passion, the depth of thought, and the content behind it is what really got me excited about showing works from this series.”

This is the first show Ash-Milby has curated at the museum as Curator of Native American Art. She says she was attracted to the four featured artists because she thought their messages of Indigenous resistance against colonization and activism deserves a wider audience.

“I definitely feel like my role as a curator of Native American art is to bring attention to art and artists that need to be seen,” she says.

Artist Lynnette Haozous creating "Into The Sun" at the Portland Art Museum, 2021.

Portland Art Museum / OPB

Ash-Milby also chose to feature New Mexico artist Lynnette Haozous. She’s Chiricahua Apache and a member of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, with Diné and Taos Pueblo heritage. For MESH, Haozous created Into the Sun, a large mural depicting an Apache woman participating in her coming of age sunrise ceremony. “Lynette described this mural as an act of ‘re-matriating’ the Portland Art Museum,” Ash-Milby said “It’s reasserting the presence of Native people and Native women by installing that temporary mural.”

Delivering a different message

The works in Mesh wrestle with the history of racial injustice and Indigenous land rights in novel ways, like the luminous photographs of Leah Rose Kolakowski and the hand-beaten bark of Lehuauakea. It’s not always an easy balance to strike.

Farrell-Smith says her artwork is also influenced by the activism she’s a part of today. She’s been deeply engaged in resisting a 229-mile-long natural gas pipeline and LNG export terminal through her family’s ancestral land in Oregon. Last year, in protest, she publicly refused to allow her art to be shown in Governor Kate Brown’s office.

Yurok Tribal Councilor Ryan Ray speaks out against the Jordan Cove LNG project at a federal hearing in Medford.

Jes Burns / OPB

“It’s a difficult thing to navigate,” Farrell-Smith said, “because within the art world, we’re dealing with capitalism, business sales, and with activism. It’s a balance of creating a platform to then leverage like I did with the Governor’s office to say, no, I’m not going to hang my art in that space. You want to weaponize it and use it to get the results that you want, or to build the awareness that’s needed to be brought to this pipeline fight.”

Farrell-Smith says she had a big smile on her face on the day the company driving the development formally asked federal energy regulators to withdraw authorizations for the proposed project, but the fight was far from over. She was already in Winnemucca, Nevada, organizing against a lithium mine the Bureau of Land Management had approved nearby by drumming up support for the Winnemucca Defense Fund and People of Red Mountain.

“I’m starting all over again,” she laughed, “in a different state.”

But just as the fight for Indigenous sovereignty doesn’t end with one small victory, artistic collaboration doesn’t end once the paintings hit the gallery wall. Farrell-Smith says she’s already talking with Haozous — who she met through the exhibition — about new collaborations. Haozous has been involved in the fight against a copper mine in Oak Flat, Arizona. They’re planning to use the Into the Sun mural from MESH to bring awareness to the threat of mining on Indigenous lands across the country.

“I’m wanting to unite,” Farrell-Smith said, “and I think that image of hers would be really powerful.”

MESH is on display at the Portland Art Museum through May 8, 2022

Listen to Farrel-Smith and Ash-Milby’s conversation with OPB’s John Notarianni using the audio player above