Editor’s Note: The events depicted in this story were reconstructed with records kept by the Portland Police Bureau, the Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office, the county circuit court, the Metropolitan Public Defender’s office, contemporaneous news accounts, and interviews with key participants. This story contains descriptions of violence.

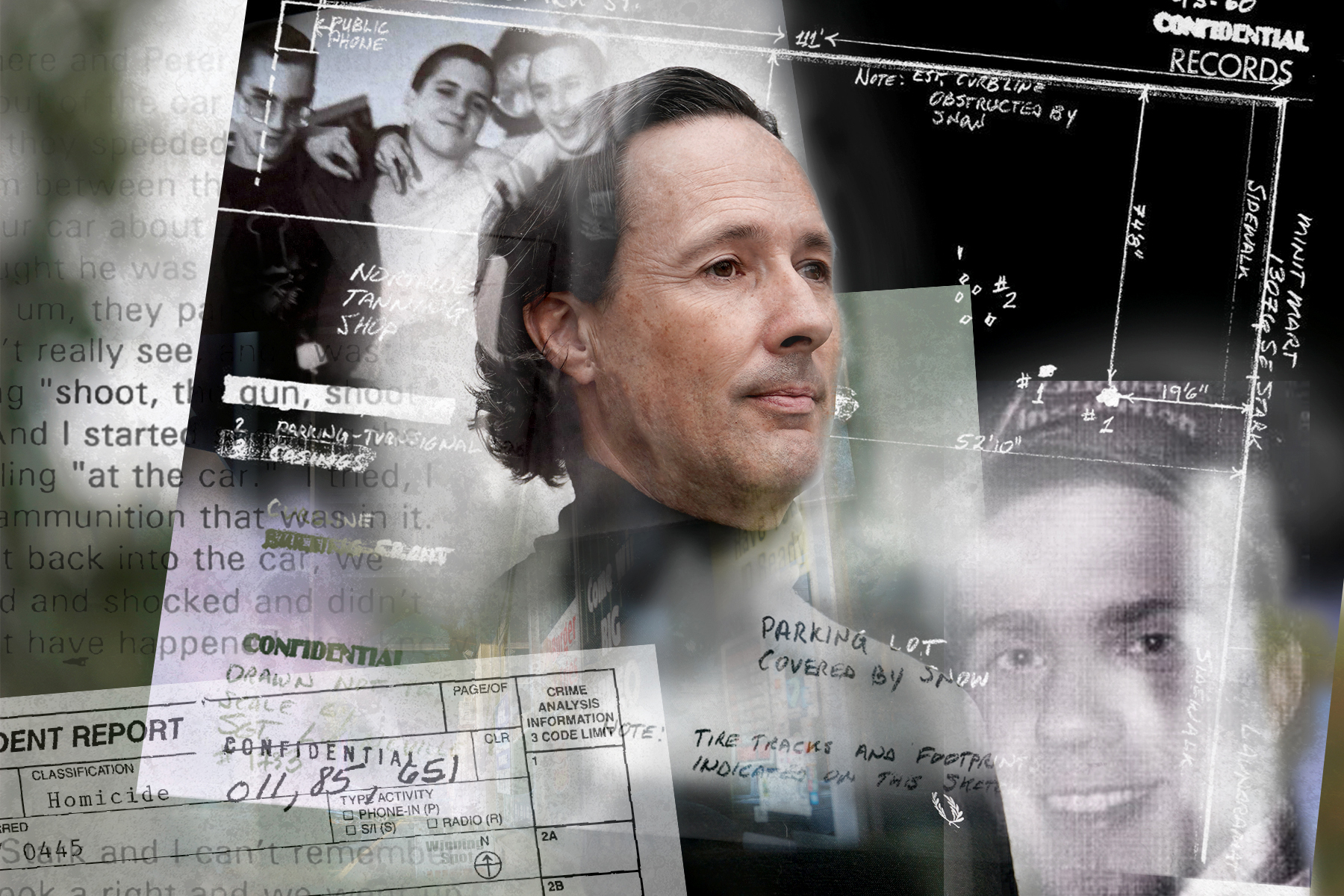

Jon Bair stood in the parking lot of a Portland convenience store one Friday in late August, his shadow falling over the very spot where he once killed a man.

The cries, gunshots and blood-stained snow are 28 years behind Bair now, the city’s war between racist and anti-racist skinheads a dimming memory. But he can’t stop thinking about the young men who once collided there, sending a neo-Nazi skinhead to the morgue.

“It just kind of gives me the chills,” Bair said. “A weird combination of feeling both heavier and kind of floaty at the same time. It just feels eerie.”

Jon Bair returns to the parking lot in the 13000 block of Southeast Stark Street where a clash between a group of anti-racist skinheads and their rivals, racist skinheads, lead to the 1993 fatal shooting of 21-year-old Erik Banks.

Conrad Wilson / OPB

The bullet Bair fired at approximately 4:40 on the first morning of 1993 shattered the rear window of a compact car and marked the moment when Portland’s anti-fascist movement — today often shorthanded as antifa — turned deadly. Bair’s painful memories of that morning flooded back with a fury last year, when history repeated itself near the end of a long summer of racial justice protests and political brawling.

On the night of Aug. 29, 2020, just a few blocks from Portland police headquarters, Michael Forest Reinoehl — a 48-year-old who described himself on social media as an anti-fascist — shot and killed an associate of the far-right group Patriot Prayer.

News of the murder floored Bair, now a 49-year-old grandfather, who had previously been impressed by the smart street tactics of Portland’s younger anti-fascists, which in spite of their brawling had never taken a life.

“And then,” Bair said, “this happened.”

‘We see them, we fight’

Portland’s skinhead wars began in the 1980s and frequently spilled into public places, including Pioneer Courthouse Square, often called the city’s living room.

Mic Crenshaw, a veteran of the same conflict in Minnesota, would later serve as a big brother and guiding force to anti-racists in Portland. Crenshaw, who helped to found the legendary Minneapolis Baldies in 1986, had stepped away from the violence by the time he moved to Portland in the early 1990s.

Crenshaw’s anti-racist views took root early. As a Black child on family trips to Alabama, he was awakened to the many dangers posed by the Ku Klux Klan, his view of the world shaken by stories of lynchings and cross burnings. As a teen, he found comradery in the Minneapolis punk rock scene, where a racist skinhead group called the White Knights recruited vulnerable kids. Crenshaw could see that young people into punk rock music like him sought acceptance outside the mainstream, and it galled him that a white power group felt safe hanging out in that subculture.

“No way,” he recalled thinking, “you don’t get to come here to do that.” So the Baldies confronted the White Knights.

Crenshaw still remembers the way “Gator,” a founding Baldie, confronted their adversaries:

“Are you White Knights? Are you white power?” To which they said yes. “And we said, ‘We’re going to give you a chance to denounce it. And the next time we see you, we’re going to ask you again. And if you’re still white power, then there’s going to be a fight.’”

After that meeting, Crenshaw recalled, a number of the racist skinheads left the white power movement, including some who defected to the other side. But not everyone quit, he explained — some remained true believers in “white power shit.”

“That was the beginning of a long period of we see them, we fight. They see us, we fight,” Crenshaw said.

In the late 1980s, the Minneapolis Baldies and anti-racists in other cities formed Anti Racist Action — better known as ARA — a coalition to combat white supremacy across the country. The group held its first meeting in Minneapolis with about 100 people representing anti-racist skinhead crews from cities such as Indianapolis, Chicago, Milwaukee and the college towns of Lawrence, Kansas, and Madison, Wisconsin. As Crenshaw later pointed out, the ARA wasn’t formed just to fight neo-Nazis — it served as a mutual aid network to take on all white supremacists.

(Left to right) Jon Bair, Mic Crenshaw, and Micah Fletcher at George Floyd Square in Minneapolis, Minn., in May 2021, a year after Floyd's murder.

Courtesy of Jon Bair

“We understood that Portland had a really bad Nazi problem, really bad,” Crenshaw said. “And there was a group of SHARPs — Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice — out here that was doing their best to fight.”

At the time, SHARP was the largest group of anti-racist skinheads in Portland, with others operating as independents. When a group of anti-racist skinheads sought to establish a Baldies chapter in Portland, Crenshaw gave his blessing, helping to give birth to the Portland United Baldies. Crenshaw moved to Portland in the early 1990s, where his brother was a roommate of Jon Bair, one of Portland’s original Baldies.

Bair pointed out that the Minneapolis Baldies established roots in Portland’s ARA, which in 2007 morphed into Rose City Antifa. That group declined to be interviewed for this story.

By the time skinhead gangs emerged in Portland in the 1980s, police often mistook them for angry punk rockers — although the racists, Bair recalled, always outnumbered the anti-racists. The warring clans later earned Portland the unfortunate nickname “Skinhead City.”

“There was a three-year period where there was not a day that went by that I did not fight, sometimes multiple fights in a day,” said former Portland United Baldies member Tom Tegner Jr., Bair’s best friend.

Portland skinheads, like others across the country, favored lace-up Doc Martens and military-style flight jackets, with patches that signified their allegiances. Racists often wore swastikas and anti-racists sometimes wore swastikas too — but theirs had slashes through them. Now and again, people in some of those groups switched sides.

The violence grew so prevalent that by 1990, some members of the Coalition for Human Dignity, a community group organized against white supremacists, sometimes carried firearms into their Southeast Portland office, according to Jonathan Mozzochi, one of the group’s former research directors. He recalled neo-Nazis showing up with baseball bats and pounding them against the steel reinforced doors of the group’s headquarters.

“Folks had weapons, had firearms to protect that space,” Mozzochi said.

One night dozens of neo-Nazis showed up and tried to break into CHD’s second story office, recalled Tegner, one of a handful of people inside. “I was sitting at the top of those stairs with an AK-47 pointing it right down those stairs, waiting for that door to come open, just scared, heart pumping,” he said. “We had guns and we were just like, ‘If they come through the door, just start cracking it off.’”

The Coalition for Human Dignity also worked to make sure teens and young adults were safe from falling under the influence of racists.

“One of the ways we did that was working with young people in the alternative music scene, Mozzochi said. “At that time, that was the first wave of racist skinheads who began to organize and who in many cases came under the tutelage of more professional neo-Nazis and white supremacists.”

‘I was a tough kid to have’

Jon Bair’s trajectory into the anti-racist skinhead scene wasn’t too different from a lot of people who joined that movement. Growing up in Portland’s Cully neighborhood, the self-described nerd hated team sports, got drunk for the first time at 13, and found himself at odds with his mom and dad at a very early age.

Jon Bair and friends during his years involved in the anti-racist skinhead movement, at his home on Southeast 32nd in the early '90s. Bair, second from right, next to Danny Oi, right, another original Portland Baldie member.

Courtesy of Jon Bair

Bair described his parents as anti-war hippies — his mom a “devout atheist,” his dad a “recovering Mormon” — and said they fought often, sometimes violently, driving him to spend as much time away from home as he could. Bair’s mother and father did not return phone calls seeking comment for this story.

“My parents weren’t necessarily super great at being parents, and I think I was a tough kid to have,” Bair said. At 15, he recalled, they gave him an ultimatum: “You either have to live by our rules in this house or you can find somewhere else to live.”

So Bair moved out.

The following year, on Nov. 13, 1988, three racist skinheads in East Side White Pride beat to death an Ethiopian college student, Mulugeta Seraw, with a baseball bat. News of Seraw’s slaying horrified Bair, by then a 16-year-old sophomore skate punk at Portland’s Madison High School (today McDaniel High). The hate crime drew international attention and marked a turning point for Bair, who began to openly identify himself as an anti-racist skinhead.

The conflict raged across town, but many of the skinheads in racist and anti-racist groups were young and lived mostly on Portland’s east side. One of Seraw’s attackers had been a homecoming king at Grant High School, with racist comrades at Cleveland and Franklin highs. Many of the skinheads — on both sides — had grown up as friends.

A composite image showing memorial street sign in the Southeast Portland neighborhood where Mulugeta Seraw, an Ethiopian immigrant, was beaten to death in 1988 by three white supremacists.

Courtesy of the Southern Poverty Law Center / OPB

One of Bair’s classmates and former skateboarding friends, Randall Lee Krager, became a neo-Nazi. Bair would later tell police about a day in 1992 when Krager had pulled next to him in his car, ready to fight: “I said, ‘Hey Randy.’ And he said that I should be white power, and I said I thought white power was dumb. And he told me to be careful, and I told him to be careful. And he drove away.”

Krager was convicted in 1992 of assaulting a Black man, leaving him seriously injured, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported. Two years later, while in prison, Krager co-founded Volksfront, a neo-Nazi group that formed chapters around the world, according to the Anti-Defamation League. Krager was released from prison in 1994 and returned the following year for what the ADL describes as threatening to kill several Jewish people and burn their homes.

‘A rare exception’

The Pacific Northwest had long spawned virulent racist groups, many calling for a whites-only, antisemitic homeland in the region, a plan sometimes called the Northwest Territorial Imperative. Their primary targets from the late 1980s to the late 1990s were Blacks, Jewish people, Asians, people who identified as LGBTQ, Indigenous people and whites who associated with people of color.

The most dangerous of the Northwest’s racist groups was The Order, which formed in Northeast Washington in 1983 and holds a place in Portland’s violent past. In 1984, the group’s founder, Robert Mathews, got into a shootout with the FBI at a Northeast Portland motel and escaped to Whidbey Island, Washington, where he perished in a house fire set by federal agents.

Right-wing militias and anti-government groups, calling themselves patriot organizations, caused a marked increase in domestic terrorism in the mid-1990s as well. The deadliest day of that era came on April 19, 1995, when Timothy McVeigh — who once held a trial membership with the Ku Klux Klan — detonated a bomb outside the Alfred P. Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people.

The Sunday edition of The Seattle Times/Seattle Post-Intelligencer, published Dec. 9, 1984.

Courtesy of Seattle Public Library Archives

Domestic terrorism spiked that year and subsided for 20 more before climbing to a new high in 2015, then spiking to an all-time record in 2020, The Washington Post reported last April. The great majority of incidents were attributed to right-wing extremists.

Experts in extremism have pointed to a number of factors that political and racist extremists have used to spur violence in recent years. A Democratic president passed a federal assault weapons ban in 1994, the nation elected its first Black president, and a Republican president championed a sense of white victimhood throughout his presidency, prompting racist mass killings across the country and an assault on the U.S. Capitol.

During the last 10 years, at least 430 people were murdered by extremists. Right-wing extremists have killed 323 people, Islamic extremists 86, and left-wing extremists 16, according to Anti-Defamation League data on what it classifies as homegrown terrorism. Most of those 16, according to Mark Pitcavage, a senior research fellow at the ADL, were Black nationalists killing police officers.

“Michael Reinoehl,” he said, “was a rare exception.”

Related: When the political divide turned deadly in Portland

The self-described anti-fascist shot and killed Aaron “Jay” Danielson last summer in downtown Portland. Danielson was affiliated with the far-right group Patriot Prayer, which along with the Proud Boys, attracted a new wave of racists and violence to Portland during the Trump years.

“It’s one of relatively few examples that are out there of left-wing extremists actually killing a right- wing extremist,” Pitcavage said. “It’s one of only two examples that I would put forward of antifa activists killing a right-wing extremist.”

The other one took place in Portland, too, and the killer was Jon Bair.

The parking lot in the 13000 block of Southeast Stark Street where a clash between a group of anti-racist skinheads and their rivals, racist skinheads, led to the fatal shooting of 21-year-old Erik Banks on Jan. 1, 1993.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

‘Shoot the car!’

Just before daybreak on the first morning of 1993, a carload of anti-racist skinheads pulled into the snow-covered parking lot of a deserted southeast Portland convenience store in the 13000 block of Southeast Stark Street. The men had partied hard that New Year’s Eve.

Now they squished together in a red Volkswagen Rabbit, five hard-core anti-racists preparing for the next fight in their long, ideological gang war. What happened next is recounted in police reports, court records, and in interviews OPB conducted with detectives and some of those present that morning.

Jon Bair, three months shy of his 21st birthday, sat in the backseat, window rolled down and gripping an SKS military rifle. He was very drunk and had smoked cannabis that night, but remained keyed up about the Nissan Sentra full of racist skinheads that had tailed them that morning, and which now eased into the parking lot just a few car lengths in front of them.

Peter Moen, sitting directly in front of Bair in the driver’s seat of the Rabbit, flung open his door and climbed out. He put his hands in the air, extending his index fingers to signal a one-on-one fight. Tom Tegner stepped out of the front passenger seat ready to brawl.

The Nissan idled for a few seconds before its driver, a neo-Nazi named Matt Porter, mashed the accelerator. The car gunned straight at Moen, striking him in the legs and knocking him to the ground, before skidding on the icy parking lot and into the Rabbit, which lurched sideways. Moen, now caught between the two cars, began to scream, and his companions panicked.

“Shoot!” someone shouted. “Shoot!”

Bair pushed the barrel of the rifle out the left rear window of the Rabbit, startling the front-seat passenger in the Nissan, Brian Westover, who shouted, “Duck!”

Bair fired a few rounds in the air, he later told police.

“Shoot the car!” Bair heard someone shout.

Bair swung the rifle barrel toward the Nissan’s trunk and repeatedly pulled the trigger, hot shell casings flipping into the snow. But the powerful kick of the weapon, which Bair later said he had never fired before, caused the barrel to bounce with each shot, until the magazine was empty.

Gun smoke filled the back of the Rabbit as Moen sped the VW out of the parking lot.

“I thought that I filled their trunk full of bullets,” Bair would later tell police, “and that we got out of there with our lives.”

A map of the crime scene from the police records investigating the shooting on Jan. 1, 1993. Jon Bair served time for the fatal shooting of 21-year-old Erik Banks, during a 1993 clash between a group of antiracist skinheads and their rivals, racist skinheads.

Portland Police Bureau

After the gunfire ended, Porter peered into the back of the car. Blood poured from the head of 21-year-old Erik Banks, the lead singer of the notorious neo-Nazi thrash band Bound for Glory. Westover later told police he climbed out of the front passenger seat and pressed clothes against Banks’ head to stanch the bleeding as Porter drove to Adventist Hospital.

A trauma team soon loaded Banks onto a gurney and wheeled him inside. But one look told them everything they needed to know: a single bullet had entered just above Banks’s left eyebrow. His heart was still beating, but he would soon be pronounced dead.

A police officer questioned Porter and Westover separately at the hospital, records show. Both lied, saying they stopped at the Minit Mart for cigarettes, discovered the store closed and then fell under rifle fire by strangers. Westover described the assault as a drive-by. But the officer later examined the bloody Sentra, finding a fresh dent in the fender and red paint markings from where it collided with the Rabbit.

The Rabbit, by then, had pulled to a stop near David Douglas High. Bair and Tegner climbed out and ran into a residential neighborhood to ditch the weapon. Bair, unaware he had just killed a man, feared police might cite him for unlawfully discharging a firearm inside city limits. About a mile from the Minit Mart, they crouched next to a fallen tree on a vacant lot and buried the weapon under handfuls of snow, moss and dirt.

Later that morning, police visited an apartment on Southeast 136th Avenue, known to gang enforcement officers as a hangout for anti-racist skinheads, and parked on the street.

Bair and Tegner felt as if they had been walking all night.

“I remember my mouth was dry, and I kept putting snow in my mouth, and I felt dizzy,” Bair recalled. Shortly after 6 a.m., they turned down Southeast 136th Avenue, happy to be home. “I wanted to go get some sleep. And as we were walking up, cops started jumping out from behind bushes and cars and all over the place.”

Police arrested the two men and took them downtown for questioning.

‘I had no idea’

Portland police detective Kerry R. Taylor, who had spent 13 years in the homicide division, sat Bair down in an interview room to ask about the Minit Mart shooting. Bair couldn’t remember the cover story Tegner had drilled into him during their grueling trek home, so he asked to speak with a lawyer — abruptly ending the interview.

Detectives questioned Tegner, who lied to them about leaving the Minit Mart before shots were fired, according to a police report. Decades later, Tegner said he doesn’t remember what he told police. “I thought I had pretty much held to a story of, we were walking home from a party, but I don’t know, maybe,” he said of the version outlined in the police reports.

One of the detectives later slid a Polaroid photo in front of Tegner, an image snapped at the morgue of Banks’ corpse, and let him know that he and Bair would likely be charged with murder.

“That’s when I lost my shit and started bawling my fucking eyes out,” Tegner recalled recently. He told the detectives he had no idea that anyone had been struck by the gunfire, and he agreed to tell them about it. But he refused to tell investigators the name of anyone else in the car.

Tegner and Bair, interviewed separately and unaware of what the other was telling detectives, each directed investigators in separate cars to the spot where they had hidden the SKS rifle, which police collected and tagged as evidence. At that time, detectives believed Tegner had probably pulled the trigger and lacked enough evidence to charge Bair.

As investigators prepared to release him mid-afternoon, a detective told Bair that one of the men in the Nissan had died.

“I just started crying,” Bair recalled. “I had no idea.”

The man Bair killed wasn’t so different from him. They had grown up as skate punks in the 1980s, moshing to punk bands like Black Flag and the Dead Kennedys, and fell into clans that put them on opposite ends of the skinhead wars. Banks’ sister would later recall that her brother had spray-painted swastikas in his basement bedroom, adding, “That’s not how our parents raised us at all.”

Sometime after 6 that evening, a Portland TV station reported in error that the man who pulled the trigger at the Minit Mart was the driver of the Rabbit. The news rattled Peter Moen, the Rabbit’s driver, who hadn’t shot anyone. He walked into police headquarters at 7:28 p.m., nearly 15 hours after the shooting, and told detectives everything that had happened. He named Bair as the shooter.

Now, the police went looking for Bair.

‘I’m going to turn myself in’

By now, Bair knew it was only a matter of time before detectives came for him. So he formulated a plan to escape.

He decided to hop a freight train to Mexico and a friend agreed to accompany him. The two men packed bags and met that night at the Crystal Springs Rhododendron Garden near Reed College. Bair would later recall seeing at least one police car in the area and he feared they were looking for him. He and his friend ran through backyards and hid behind a convenience store.

Jon Bair’s prison ID card. Bair turned himself in days after a shooting in 1993 that left one man dead, and months later pled guilty to first-degree manslaughter and unlawful use of a weapon in the shooting of Erik Banks.

Courtesy of Jon Bair / OPB

There, Bair found himself overcome with doubts. He knew that running away to Mexico would leave people with the impression he had intentionally killed Banks. Despite his clashes with his parents, Bair loved them and his brother. He worried about what they would think, what it would be like to never see them again. He wondered what God would think. Now, confronted by the enormity of what he was setting into motion, he realized there was only one path.

“I’m going to turn myself in,” he told his friend.

Bair’s companion told him that was a terrible idea, he recalled, because of what might happen to him in a prison system teeming with racist gangs. He feared the Aryan Brotherhood would target him behind bars. But he knew that running away from his country, his family and his friends would be the death of the life he knew. At that moment, he recalled telling his friend, “This is what I have to do to be right with me.”

By now, it was early on Jan. 2, 1993. Bair decided they should splurge with some of the money they were going to take with them to Mexico.

They caught a taxi to Shari’s diner in Gresham. There, Bair recalled, he was too nervous to eat, picking at his big plate of steak and eggs. Eventually he stood up and walked to the payphone with the business card of one of the detectives in his hand. It was 4:50 a.m. when he reached an officer in the Portland police detective’s unit, saying he wanted to speak with Det. Kerry Taylor, who was not yet in the office. Bair told the officer he wanted to turn himself in for the slaying of Erik Banks, and he let them know where he was.

He returned to his seat and told his friend that he should probably clear out before the cops arrived. An hour or more passed before Bair, staring out the window, saw the first of several patrol cars pulling into the parking lot. He made his way to the front of the diner and opened the door, feeling the cold air against his face. Decades later, he would vividly recall the next few moments as he walked out to greet the officers.

“Hey,” he later recalled saying, “I think you guys are looking for me.”

Police pulled their guns and began shouting commands all at once, a confusing tangle of orders that ultimately put him on his knees, fingers interlaced behind his head. He saw a sea of faces, including a family with small children, staring at him from inside the windows of the restaurant. And he was glad, as police cuffed him, the officers arrested him in a public place.

‘My son ended up dead in a city with no family or friends’

At 6:18 that morning, Bair and detective Kerry Taylor took seats at city police headquarters with a tape recorder rolling.

In the space of 40 minutes, Bair gave a complete confession to his role in the slaying of Erik Banks. He told Taylor he had fired all 10 of the rounds he had loaded into his rifle and that he was scared to death at the Minit Mart because he had just watched racist skinheads run down his friend Peter Moen, the driver of the VW Rabbit.

“They followed us around with their headlights off,” Bair recalled to the detective. “I thought they were gonna kill us.”

Months later, Bair would plead guilty to first-degree manslaughter and unlawful use of a weapon in the slaying of Banks.

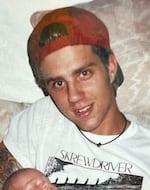

In this undated photo, Erik Banks poses for a photo while holding his baby, wearing a T-shirt from a white supremacist band, Skrewdriver. Banks was the lead vocalist for the neo-Nazi band Bound for Glory.

Courtesy of Jen McGill

By then, Banks’ affiliation as Bound for Glory’s lead vocalist had made him a martyr for neo-Nazis across America.

“It’s not like he was some sort of innocent, random bystander,” the ADL’s Pitcavage said. “At the time, and for some time afterwards, it was one of the most popular white supremacist, white power bands in the country.”

On June 14, 1993, Banks’ mother, Lillis Gjertson, and his younger sister Jen attended Bair’s sentencing.

“I know that the state, as well as many other people, have no sympathy for the fact my son was murdered,” Gjertson told the courtroom. “Because of the group that he was with, there is guilt by association. But none of you knew my son, and so I must be here today.”

She described her son as funny and loving, but noted that when he was 17 — and having trouble finding himself — he had the misfortune of getting involved with a racist skinhead group. But he made strides in the last year of his life, she said, earning his GED. Banks was engaged to be married and had an infant son. He had come west to earn money aboard fish processing boats in Alaska, Gjertson said. But the work did not materialize when they arrived, and they ended up homeless at Christmastime. The fishing boat that her son would have shipped out on departed without him two weeks after he died.

“So, with the help of the only organization they were familiar with,” Gjertson said, “they ended up in Portland staying with people they didn’t know. They ended up caught in a war between gangs, and my son ended up dead in a city with no family or friends.”

She then focused on Bair.

“On that night of January 1st,” Gjertson said, “you were the judge and the jury, and when you lowered that gun and fired you became the executioner and condemned my son to death. If I was given the choice, you would receive the same sentence you gave my son.”

Gjertson’s words struck Bair like slaps, a scolding he took gravely.

The death of her only son turned Gjertson into a hermit, an utterly different person, her daughter Jen McGill recalled years later.

In this undated photo, Erik Banks (right) poses for a photo with his sister Jen McGill, left, and their grandmother. Banks is wearing a T-shirt from a white supremacist band, Skrewdriver.

Courtesy of Jen McGill

“How do you explain to other people your son was a skinhead and he got shot? You can’t really ask for people’s empathy or sympathy or to grieve with you because they think that he’s a monster, that he deserved it,” she said.

One of Bair’s defense lawyers, Lynne B. Morgan, believed he warranted a shorter sentence for what she had described in court papers as a reckless but unintentional shooting during a clash between warring skinheads. While negotiating a plea with prosecutors, she pointed out that Bair was vulnerable to violence in prison.

“Mr. Bair is small in physical stature,” Morgan wrote. “Further, because of the nature of this particular incident, he will be a target of violence from racist skinheads and the Aryan Brotherhood.”

The judge sentenced Bair to five years in prison.

Later that summer, he landed at the Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution. Corrections officials assigned him a job in the prison college, where he served as a teacher’s assistant in the English-as-a-second-language program.

The mostly Latino students in the program took one look at Bair — pale, short, skinny, afraid to stand up to those who bullied him — and thought he was a child molester. A Latin gang member confronted Bair with this suspicion, and he assured them he was not a pedophile. But the man demanded proof. So Bair shared his criminal case papers with the Mexican Mafia, he later recalled.

A day or so later, he said, a member of the gang told Bair that they felt sorry for him because he was so afraid of white supremacists. He told Bair that from that day forward he was to join them at their weight pile in the yard, get in shape, and quit worrying about the white power gangs, as they were vastly outnumbered by the Mexican Mafia.

“They’re not a problem for us,” Bair recalled him saying. “You’re going to be an honorary Mexican.”

Back in Portland, as a Time magazine writer noted that summer, the skinhead wars continued, with “rival gangs of bald men with tattoos” lending “this chamomile-and-beansprout metropolis a Mad Max edge.”

‘We never beat the racism out of anybody’

Last year, when anti-fascist Michael Reinoehl shot and killed Jay Danielson in downtown Portland, Bair was forced once again to examine his own violence so many years ago. The two crimes bore similarities. Political opposites had escalated from street brawls to gunplay. Bair had carried a rifle to defend himself against armed bigots. Reinoehl had carried a pistol to a protest, opening fire on Danielson, who also was armed with a holstered handgun.

Bair concluded that he and his anti-fascist comrades had become as brutal, remorseless and dehumanizing as their adversaries.

“Those were the things we originally banded together to protect ourselves from,” Bair said.

The racists, he said, just slipped underground and came back later — much more visibly during the Trump years — with a slicker, toned-down package, but still preaching hate.

Mozzochi, who worked against Portland’s virulent racists with the Coalition for Human Dignity, believes that not only are there greater numbers of far-right, quasi-fascist groups like the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer today, but they have better access to established political organizations, such as the Republican Party.

“You did not see that back in my day,” he said. “They are far better organized and far more lethal and have a greater capacity today than they did back then.”

Bair doesn’t think violence will turn back the resurgent right.

“We never beat the racism out of anybody,” he said.

In August, Bair returned for the first time in nearly 30 years to the convenience store parking lot where he took Erik Banks’ life. Rush hour traffic roared along Southeast Stark Street. Customers came and went, unaware of the site’s significance. Bair’s hair is now long. And as he walked across the pitted asphalt lot, he struggled with a bog of emotions. He still believes that his anti-racist cause was right, but acknowledged that what he did was tragic and stupid.

“We thought if we fight these Nazi guys and we’d beat them up and run them out of town, then we won’t have racism anymore,” Bair said. “We had no idea that if we set out to battle white supremacy, that we were battling this giant monster that was much of our country and our heritage and our history. … I had no idea that I could still benefit from being a white male in a white supremacist society.”

Bair has managed to build a loving family since getting out of prison — today he is a proud dad and grandfather — and a sought-after master carpenter specializing in historic restorations. Still, as he drives around Portland these days, he’s overwhelmed by the darker corners of his life — the spot where a friend overdosed, the bridge where several others jumped to their deaths, and yes, the parking lot in which he killed Erik Banks.

Bair wishes he could talk to his younger self. He would tell him of the nightmares that would later haunt him, and maybe whisper a few words of wisdom: “Don’t get into the car, don’t go to this fight.” He would stop the killing before it happened.

“I’ve been able to try to change and learn and grow and become a better person,” Bair said. “Obviously, Erik Banks didn’t get that chance.”

Jon Bair stands in front of his former home in the 3800 block of Southeast 32nd, Sept. 29, 2021. Bair says he was deeply involved in the skinhead world when he lived here, and for several years, it was a big hangout for other members of Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice. Bair had recently moved out of the home when the shooting incident that killed Erik Banks occurred in 1993.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

Despite his remorse, Bair never reached out to the Banks family in all the years that passed, partly because he was forbidden from making contact while on parole. Today, he feels that trying to connect with the family would be inappropriate.

Banks’ mother died earlier this year, and McGill doesn’t think her mother ever forgave Bair.

“Now that I look back at it,” she said, “I think these were all kids, all immature, not even capable of thinking things through clearly with consequences. And I mean, even my own brother, I think it could have been him that shot someone.”

McGill said all the skinheads that night made bad decisions. “And unfortunately, my brother was the one that paid the ultimate consequence for it.”

Now she considered Bair himself, saying that as long as he’s changed, it’s probably easier for her and her family to forgive him.

“I had this kind of epiphany where I came to believe that the weight of taking someone’s life is really equivalent to the weight of wiping out a whole planet or a whole universe because that is what effectively happened for that person,” Bair said. “That kind of landed on me at some point early on. That’s a pretty heavy feeling.”

When he was 20 and running from police, Bair had cooked up a plan to flee Portland, to run away forever from the life that led him to kill.

Now he really is going. He’s put his house on the market and plans to move to California. He’s done with the politically and racially motivated violence — even if the city he’s leaving is not.