Veterinary Medicine was hit hard during the pandemic with understaffing and many in the industry being overworked. Oregonians have had to face long wait times with some unable to see a vet for their pet in need as a result.

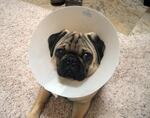

Flickr/Claire

While ICU beds are full and health care workers are overworked, they’re not the only ones dealing with an influx of patients. Throughout the state, veterinary hospitals and clinics are facing large amounts of new patients, understaffing and burnout. Beyond this, Oregonians seeking care for their pets are seeing longer wait times and being referred to locations other than their neighborhood vet. We speak with Dr. Heidi Houchen, president of the Oregon Veterinary Medical Association and Blood Bank Director at VCA Northwest, as well as Ron Morgan, CEO of DoveLewis Emergency Animal Hospital.

The following transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: From the Gert Boyle studio at OPB this is Think Out Loud, I’m Dave Miller. Over the last year and a half, or more than a year and a half, we’ve talked a lot about dangerously full hospitals and ICUs and overworked healthcare professionals, but we’ve basically only been talking about human health care. It turns out that the pandemic has had similar effects on animals as well. Throughout the state, veterinary hospitals and clinics are facing large numbers of new patients, jammed up emergency rooms, understaffing, and burn out. For more on what’s happening, I’m joined by Heidi Houchen, the Blood Bank Director at VCA Northwest and the President of the Oregon Veterinary Medical Association, and Ron Morgan is with us as well. He is the CEO of DoveLewis, an emergency animal hospital in Portland. Welcome to you both.

Heidi Houchen:Thank you.

Ron Morgan: Thank you, Dave

Miller: Ron Morgan first, what is a day like at DoveLewis these days?

Morgan: It’s crazy actually. It’s hit the ground running, non-stop treatment of very sick animals, both in our emergency side of our hospital, our ICU, and the specialists in our hospital. The patient volume is something that we’ve just never experienced, other than like super busy holidays. Every day is the Fourth of July at DoveLewis right now.

Miller: Is the Fourth of July known as a really bad or busy day for vets?

Morgan: Yeah, any major holiday is really tough for a veterinary emergency hospital. It’s one of those days where you could have 100 plus patients coming in in a 24 hour period, and treat three or 400 a couple of days. So quite literally in the last year and a half, almost every day has become something like that.

Miller: Heidi Houchen, what are some of the reasons for that? In other words, why is this so bad, and so bad for so long?

Houchen: That’s a great question. There’s a lot of answers to that. A lot of people adopted pets during the pandemic, which is great because there’s nothing better, at least with my anxiety, than having something furry and loving unconditionally next to you. So that’s terrific. And people were home, and they noticed things both acute and chronic with their pets, which again is terrific, we want to take great care of pets. And then that meets the inevitable, which is we had to adopt protocols for both the safety of the public and of our employees and in accordance with governmental mandates, and that takes a lot of time and effort to keep everybody safe. So there’s a steep increase for demand for veterinary services at a time when we’re asked to do things that are really not as efficient as before, curbside. It takes a lot of time to do each case now there’s a lot of back and forth. We’re dealing with medical issues, we want to make sure that we’re getting things right in terms of not only going over estimates to make sure that owners know what sophisticated medical or surgical procedures are going on. So it takes a ton of time when there’s a steep demand for it.

Then add to that, we had pre-pandemic issues such as we’ve always for a very long time had support staff, tech shortage, and ER doctor shortage. To use a metaphor from sports, we don’t have a very deep bench right now. So if someone is ill, or their child is ill, or there’s childcare issues, it really affects us. There’s a ripple effect. And then add to that what everyone else is dealing with, supply chain issues. We are waiting for medications and equipment and supplies and that impacts us too. So it’s really, in a nutshell, as Ron said, it’s Fourth of July every day for ER doctors and specialists, at the same time when we are struggling to deliver things in the same way.

Miller: We asked our listeners about their experiences. We got a lot of voicemails. Here’s one from Kathleen Kelly from Portland.

Kathleen Kelly: I recently had an emergency with my dog, and I had a very hard time getting him into an emergency clinic. All clinics that I called were referring us to go to one clinic across town, and they were overloaded. And we were told by the different clinics that they were at capacity, couldn’t take anymore dogs or cats. It was a nightmare that went on for a week. I didn’t know if my dog was going to live or die. It was dire.

Miller: Ron Morgan, how common is a story like Kathleen Kelly’s? Where there’s an emergent situation, and yet care is simply not available for days.

Morgan: Unfortunately, it’s very common right now. It has never been like that, pre-pandemic. It’s been a struggle. What’s happened is several of the other emergency hospitals in town have had to reduce receiving or reduce hours related, as much as anything, to staffing issues, as Heidi alluded to. There’s always kind of a shortage of staff, and so what’s happened is the patient load has transitioned over to the emergency hospitals, because the regular veterinary clinics are also having a hard time getting people in. Where you might have been able to see your regular vet within a couple of days for an appointment, now it’s a week or more related to pandemic protocol staffing issues.

And so a lot of the emergency rooms have had to stop “receiving patients” when they’re full and at capacity. Listening to that voicemail, my guess is, based on our experiences those other emergency hospitals, when she says across town, were probably recommend going to DoveLewis. We’ve managed to stay open and not stop receiving. It’s just part of our mission to always be open and stay. But we’ve also had to do things that we never expected to do before too. So our wait times have been historically long, we’ve had to take waiting lists of people. When people come into Dove, we triage them. If they are very stable, we’re able to put them on a waiting list and let them go home and wait. For a long time during the pandemic, we were having people wait outside for hours and hours. It’s something that nobody wants to experience. It’s really been a difficult emotional time for both the pet owners and staff.

Miller: So in some of those days, you had a line of people outside on the sidewalk holding or near their sick dogs or cats, just waiting to be able to go inside?

Morgan: Not necessarily waiting. A lot of them were in their cars. We had protocols, we had to change 60 protocols at DoveLewis just to manage the requirements of staying open as an essential business. And so not having people come into the waiting areas, for instance. Now, as a nonprofit, we treat a lot of people that maybe don’t have cars and come to us by another mode of transportation. So we were able to let people in and take care of them if needed. But for a long time, Heidi alluded to curbside. So that is referencing people waiting in their cars and doing curbside check in and check out. We had people in their cars for long periods of time, and had to make accommodations for hot weather and cold weather and things like that. It’s been an amazing period of time, and we feel like, in many ways, we have had to not give the level of service that any of us wanted, not just at DoveLewis, but other clinics as well. But I think everybody’s just doing outstanding, and their most to treat the extreme volume of patients coming in.

Miller: You mentioned curbside drop offs or waiting or pickups. We actually got a call that mentions that that I want to run by both of you. This is from Renee, who called in from Beaverton.

Renee: I had an elderly dog that needed some frequent vet visits during the pandemic. It was curbside drop off and curbside pickup. So a vet tech would come out to the car to come get her. This is the first time in her 16 year life that I didn’t go inside with her, so that was a little odd. So sadly, in August of last year, I had to say goodbye to her, and make an appointment to have that done at the vet’s office. And the hardest part about it for me was that I had to go all by myself with her. I couldn’t have anybody else with me. So that is the worst part of it for me. If this were normal times, perhaps other family members and friends could have gone with me.

Miller: So Heidi, obviously Renee is talking about two different things: the pain of being alone when her dog was euthanized. But before that, the challenge of curbside dropoffs. And I should say, we actually got a number of calls from people who talked about that in very emotional ways. What has that been like from the veterinary perspective, to not have the people there for the most part when vets and vet techs are taking care of the animals?

Houchen: Gut wrenching, heartbreaking, devastating. The reason veterinarians and veterinary technicians and our whole staff from assistance all the way up at hospitals across the city and state, and I’m pretty comfortable speaking for everybody, the reason we go into this is because we’re basically caretakers, and our prime directive is to eliminate animal pain and suffering, and human welfare. So when we have to take those animals and we hear those stories, if you can multiply that by 10, by 100, by 1000, that’s what our staff is dealing with every day. As Ron said, every day is the Fourth of July, and we have a significant number of those that, to not have those owners in the room and have those owners have the support they need is challenging for us. I’ve had friends on the east coast where they haven’t even allowed, because of their state or local regulations to have the owners in with their pets. They’ve had to do it through glass. We thankfully in this area found innovative ways to make sure that at least the owners are there with their pet. But it is absolutely devastating to us to have to have that happen every day. And we want animals to be with their owners. And it’s benefiting to us, both the nonverbal cues as well as the verbal cues, when we’re communicating with people, are essential to deliver the highest level of care. It is difficult to deliver the care that we want and we need and we find satisfaction our jobs in by not having people in the room. So we definitely want them in.

But at the same time, we have to keep people healthy. We have to follow mandates, we have to keep our staff healthy. So, as I said before, one person ill in our staff is a huge ripple effect. We don’t have a large amount that, if somebody’s out and quarantining, that can fill their positions, so we have to keep everybody healthy. So it’s this continual compromise that doesn’t allow us to feel great about things, but allows us to stay taking care of people’s pets. And it’s been extremely stressful for us. Veterinarians are stressed about keeping pets healthy in the Oregon community. They’re stressed about making sure pet owners are educated and involved and supported. They’re a huge part of their animal’s care. They’re stressed about making sure their staff are supported and healthy and taking care of their families. The constant pressure, maintaining a level of veterinary care that we hold ourselves to as Ron alluded to, we hold ourselves to a very high standard, and we go into this profession because we want to maintain animals and humans health. And then we’re stressed about the mounting workload.

We don’t see light at the end of the tunnel at this point. We want to keep up the level of care, but it’s tough. It’s all those things, and it’s taken a huge toll on the veterinary community right now. It’s very much in parallel with what you mentioned at the top of the hour. It’s very much like what’s going on, because we’re essential workers, just like human health care workers.

Miller: I want to play another voicemail for both of you, and this gets to what you were just getting at in terms of more of the parallels between animal health care and human health care. This came in from Alex Simpson, who owns Grateful Heart Veterinary Hospital along with his wife. Let’s have a listen.

Alex Simpson: Every clinic in Portland is overloaded, including the emergency and urgent care clinics, and we’re all scrambling just like human health care to provide as much care for as many pets on a daily basis. However, clients are getting aggressive, they’re getting difficult and argumentative and assuming we don’t care, or that we’re trying to purposefully deny care to clients, which has been very difficult just like in human health care.

Miller: I’d love to hear from both of you on this, but Heidi first, how are some humans dealing with everything you’ve just been talking about?

Houchen: I just went through the stresses on us. So we know when we look at a client’s face, we understand whether it’s curbside or inside the hospital, exactly what’s going on. We feel exactly the same way they do. And it’s tough because they all come in, nobody wants to see you when you’re dealing with their sick pet. It isn’t a happy situation. There have been a lot of very upset, unhappy, stressed clients, and they have a tendency to take it out on the staff.

So one of the things we’ve said, just like in human health care, the most important thing that you can do in the pandemic right now is please be kind. Please be kind, please be patient with veterinary staff, know that these people are doing their job for the love of animals and really no other reason right now in the pandemic, and it’s bothering them just as much as you that you can’t get dealt with in the time that you want to be dealt with. And the kinder you are to them, the more chance we have of having staff, because the burnout is a very real thing. I’ve talked to everybody across the city, everybody across states, and then my colleagues throughout the United States, and it’s happening all over. When people act out or berate veterinary teams, the damage you cause causes a ripple effect. It actually hurts the amount to level the degree of care we can give. So the most important thing you can do right now is just be kind to the veterinary staff.

Miller: Ron Morgan, what have you seen?

Morgan: Yeah, we definitely have experienced some of that. And it’s understandable. We’re having people that are waiting and waiting, and all they want to know is is their pet going to be okay. So we’ve all had to live through these incredibly difficult periods where we’re doing things that are unusual. So we’ve seen some instances. As Heidi said, it’s a daily occurrence. What I guess I would say is, people who work in veterinary medicine or some of the most compassionate, amazing people that you’ll ever come across.

And there’s a mental health crisis in veterinary medicine that a lot of people don’t talk about. People who work in veterinary medicine are actually four times more likely to commit suicide than than someone in the general public, and actually two times more likely than people who work on human health care. And at DoveLewis, we have a licensed clinical social worker on staff just to help create well being programs for our staff. So it’s something that proactively we look at a lot. This pandemic has been devastating for people working in veterinary medicine, throughout the state of Oregon and across the country in terms of not being able to provide the level of medicine sometimes that we want to, because of the volume of patients and the protocols involved. And so, what Alex mentioned is true, and at the same time, we understand the situation, and I think that the people on the front lines of veterinary medicine have been doing a heroic job. It’s been an exhausting 18 months, and to Heidi’s point, we’re really hoping we just hang on to our staff at this point. This is not over. There is no light at the end of the tunnel.

I can tell you that once we were able to move away from curbside at DoveLewis, and let people in our lobby and have those personal interactions again, that the interactions with people were so much more positive. Just having humans being able to see each other and play on their emotions and deal with him. The air went out of the anger level a little bit. So that kind of speaks a little bit to the protocol is really playing into the situation and the wait times.

At the end of the day, people just want to make sure their pets are okay. Our staff all just want to do their best job. And if I hope everybody can remember that when you do interact with your veterinarian and your veterinary staff, because they’re in it for all the right reasons.

Miller: I want to play you both one last voicemail, because this one surprisingly actually has a sliver of hope in it. This is Michael Parker from Salem.

Michael Parker: My family had a 14 year old labrador, Stella, who just after New Year’s Eve back in January had trouble standing up and using her back legs. She quickly lost her appetite, and my wife and I and my daughter decided that it was probably the end of the road for her. And so we called our local veterinarian that we’ve taken her to her whole life, and they couldn’t see Stella for seven days, even to have a rainbow bridge appointment to put her down. And so, thankfully, during those seven days she started to walk again and started to eat again. And by the time we got her to the vet, they told us that she’s not done yet, she has more life in her. And so we’re so happy to be able to take her back home. She stayed with us another eight months. Every day was very special. So, in a lot of ways, the way the pandemic affected delays at the vet was a good thing, a blessing for our family, because it bought us eight more months of invaluable time with our dog.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.