The Oregon Health Authority’s COVID-19 vaccine distribution plan promised “a commitment to health equity” where a person’s access to the potentially life-saving vaccine wasn’t dependent on their social class, race or ethnicity.

But data on the number of people vaccinated by ZIP code released by OHA this week show glaring inequalities, four months into the effort to vaccinate every Oregonian.

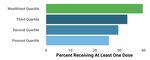

Vaccination Rate by ZIP Code Income Quartile

Source: Oregon Health Authority, ESRI. / Graphic: Jacob Fenton

Across the state, people in wealthier neighborhoods were one-and-a-half times as likely to have received at least one dose of vaccine as people in the poorest areas.

In the wealthiest quarter of ZIP codes in Oregon, where per capita income is $36,189 or greater, 40% of people had been vaccinated as of April 12. In the poorest quarter, where per capita incomes are less than $26,424.00, it was just 26%.

It’s a correlation that’s been seen across the country, from Connecticut to California.

The data release revealing the inequity comes as another wave of COVID-19 sweeps through Oregon. Daily cases, hospitalizations and deaths have all increased significantly.

Experts say the data reflects many of the inequalities embedded in American health care and an obstacle to achieving herd immunity.

“Tackling this pandemic, you have to remember that a large share of our population will need to be immunized — between 70 to 85% of the population,” said Daniel Lopez-Cevallos, an ethnic studies professor at OSU.

“It is in everybody’s interest, high-income communities included to have those in the lower

income bracket, and across racial and ethnic groups, be vaccinated.”

Available data also suggest vaccination disparities based on ethnicity, as well as income.

While people living in ZIP codes in the Portland metro area with larger proportions of white people generally have higher vaccination rates, the trends are more complex in rural parts of the state.

Separate data on ethnicity OHA publishes on an ongoing basis shows the vaccination rate for Latinos in particular trailing whites and other groups. They account for 13% of the state’s population, about 25% of people infected with COVID-19, and just 7% of people vaccinated.

This week, the Latino Network and other community organizations said the state and health systems’ efforts to get the vaccine to Spanish speakers and those who lack insurance have been too timid and need to be scaled up.

Related: Vaccine gap plagues Oregon’s effort to protect Latino communities

“It’s what we need to be doing in so many more places in our state: creating the space where people belong, and they know the vaccine is meant for them, that their lives are worth saving,” said Serena Cruz, with the Virginia Garcia Memorial Foundation.

To date, Cruz said, the work has been largely left to specialty clinics like hers, which receive far fewer doses of vaccine than larger mainstream health care providers, like Kaiser Permanente and Providence.

OHA Director Patrick Allen said he would work on several specific proposals the community leaders called for. Those include a Spanish language hotline to help people register for vaccination appointments and a benchmark for how many vaccinations should be going to Latinos to ensure parity.

“We stand ready to double down our work with these partners, and come up with new strategies, new investments, and make sure we do what we need to do to get people vaccinated,” Allen said.

Gov. Kate Brown says she’s aware of the problems of unequal access in the roll-out of the vaccine.

“We are doing more than we’ve ever done before and it’s not enough,” she said. “There are a number of efforts to reach these hard-to-reach communities.”

COVID-19 vaccine preparation at a drive-thru vaccination clinic at Portland International Airport, April 9, 2021.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff/ OPB

Experts say a number of factors likely explain why people in wealthier neighborhoods have been vaccinated in greater numbers.

Oregon’s eligibility system gave priority to health care professionals, teachers and people who were 65 and older. Medical professionals tend to have higher incomes, and older individuals may have accumulated a lifetime of savings and wealth.

The technology requirements for signing up for an appointment and the need for access to transportation to travel to a vaccination site are also a factor.

“Requiring online registration for appointments confers ready access to people who have available internet resources, computers, and just as importantly time to work through the registrations process,” said Courtney Campbell, an OSU professor and expert in medical ethics.

Campbell believes people working in lower-income jobs have found themselves “doubly disadvantaged,” by the state’s initial eligibility criteria and their lack of access to resources.