Earthquake scientists studying a fault off Oregon’s coast have figured out a new way to map the layers of sediment and rock under the ocean floor. They did it using whale song inadvertently recorded by their instruments.

Fin whales are among the loudest animals on the planet. Their songs can reach nearly 190 decibels – louder than the loudest concert, louder than a gun shot, louder than a jet engine. At the same time, the pitch is so low that it’s at the edge of humans’ ability to hear.

“Most people would say (without enthusiasm) ‘Eh, whale call…’. Other people have seen them and think of them more-or-less as noise,” said Oregon State University seismologist John Nabelek.

But Nabelek and his then-doctoral student Vaclav Kuna decided to look more closely.

Photograph of fin whale taken during Oregon State University Marine Mammal Institute's 2014 tagging field season off southern California.

Oreqon State University Marine Mammal Institute

Nabelek was using ocean-bottom seismometers to study the Blanco transform fault about 60 miles offshore from Port Orford. These sensitive instruments are used to measure vibrations from earthquakes, but they pick up the sound waves of whale song as well.

Fin whales are rather long-winded, and the researchers ended up with hours of these calls on tape. They were able to use the recordings to pinpoint the location of the singing whale within about 100 feet.

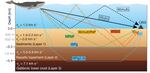

The seismometers not only picked up soundwaves that traveled through the water, they detected vibrations of the song that had penetrated deep into the ocean floor – up to 1.5 miles down.

The researchers realized they could analyze these underground sound signals and determine how thick the major geologic layers are in the area where the whale sang.

“It was not just sediments that showed up, but also the deeper layering in the crust,” Nabelek said.

Nabelek said seismologists need to know the composition of the ground where earthquakes occur to accurately pinpoint their origins. Usually this mapping work is done with air-guns, which require special permitting because of the potential for harm to marine life, including whales.

Using fin whale calls doesn’t provide the same level of detail as air-gun mapping, but the researchers say this could be improved by using calls from other types of whales, like sperm whales, with higher pitched calls.

Oregon State University graphic showing how sound waves from fin whale song interact with the ocean and its floor.

OSU / OSU

“We see the thickness quite well, but if you wanted to see layering in the sediment, you know the higher resolution, you need to have the higher frequencies,” Nabelek said.

Nabelek likens the potential difference as being able to see all the colorful layers of the Painted Hills of Eastern Oregon versus an indistinct mound of dirt.

The research is published in the journal Science.