“When you're harvesting geoducks, it's like picking up $20 bills,” says Bob Sizemore, WDFW geoduck research scientist.

Laura James, EarthFix/KCTS9

Of all the shellfish that sell on the black market, one clam is above the rest -- the geoduck.

Pronounced "gooey-duck," these hefty clams bury themselves in sand where they stay for 100 years, doing little more than stretching their meter-long, fleshy siphons up into the water column to feed on phytoplankton.

In shallows when tides have retreated, people dig up geoduck clams with shovels. In deeper areas, scuba divers spray high-pressure hoses into the seafloor to unearth them.

WATCH: How Black-Market Poachers Exploit The World's Biggest Burrowing Clam

Wholesale geoduck prices at Puget Sound docks have more than doubled from $4 per pound in 2006 to as much as $15 per pound today. With the average adult geoduck weighing one to three pounds, a good geoduck diver can harvest thousands of dollars’ worth in a few hours.

“When you're harvesting geoducks, it's like picking up $20 bills,” says Bob Sizemore, lead research scientist for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

The total amount of geoduck catch reported by fishers (landings) has remained fairly steady since a 2.7 percent harvest rate was established in the 1980s. At the same time, the overall value of geoduck prices has risen dramatically.

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

Rising demand, especially among China's growing middle class, has sent geoduck retail prices in Asia to as high as $150 per pound. Those soaring prices have created an incentive for poachers back in Puget Sound, giving rise to an international black market.

About 90 percent of the geoducks harvested in the United States are sent to Asia, where they are served raw at sushi restaurants in Japan, used in soups and stews in Korea, or cooked in a fondue-style hot pot in China.

A Midnight Patrol

It’s past 11 on a rainy January night in Puget Sound. Clouds blot out the moon and the stars, making it nearly impossible to tell where the sky ends and the water begins. A boat runs blind through the inky blackness — no onboard lights, no radar signals announcing the location. The motor’s hum and the faint spray of bioluminescence in the boat’s wake is the only evidence of its presence.

The boat is a Fish and Wildlife patrol vessel and Sgt. Erik Olson of Washington State Fish and Wildlife is at the helm. His partner, Officer Carly Peters, peers through night-vision binoculars, calling out directions to avoid floating logs or buoys.

Sgt. Erik Olson, WFDW, patrols Puget Sound by night looking to catch shellfish poachers in the act.

Katie Campbell, KCTS9/EarthFix

"We're looking for anything and everything on the water tonight," Olson says. "The harvest location is the only place we're locked solid in terms of if we caught someone poaching. It is the hardest place to patrol, but we've got to give it a shot."

Olson scans a fraction of that shoreline appearing on the radar screen. He's looking for small red dots offshore that could be a boat of divers illegally harvesting geoducks.

More Online

Watch:

'Wildlife Detectives: Hunt For Northwest Poachers'

'Wildlife Detectives: Poaching The Puget Sound'

Explore:

Download the Wildlife Detectives ebook for free from iTunes

Soon they see a blip. It's another boat that's running without any lights. Peters can barely make out a boat with a couple people on board.

"They're supposed to have that all-around white light," Olson says. "It looks like they're looking for something. What are they looking for?"

He squints.

"Now they're hoofing it," Olson says. "All right let's go stop them."

Olson turns on the overhead police boat flashers. The other boat slows. It's a farmed shellfish crew. They say they're not harvesting tonight, just checking on some of their beds. Olson checks their registration and tells them they need to have an all-around light on their boat.

"Well, that was really anti-climatic," he sighs after climbing back aboard the fish and wildlife boat.

Olson and Peters continue patrolling the darkness. Over the course of two full nights, they will stop a handful of boats on the water. But they find no one who seems to be poaching geoduck or other shellfish.

"I guess you always wonder what you're missing," Olson says. "Our biologists have confirmed that these areas are being poached. I just continually try to rack my brain to try to figure out ways to tackle this."

The geoduck lab

Despite the black-market pressure, Washington’s wild geoduck fishery has been called one of the best-managed fisheries in the world. That’s in part, officials say, because of the ongoing scientific research that informs the harvest limit.

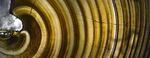

From a WDFW lab in Olympia, Sizemore and his team study geoducks by analyzing their shells. They cut cross-sections and look at them under a microscope to determine how old they are and what kind of a life they’ve had.

“They have rings that you can count, just like a tree,” says Bob Sizemore, turning a hard white shell over in his hands. “Some of these clams are 160 years old. They were alive when Abraham Lincoln was president.”

A cross section of a geoduck clam's shell shows its growth rings.

WDFW

The rings reveal their growth rates. And that information helps Sizemore’s team decide how many can safely be harvested. These slow-growing, long-lived clams have been called Puget Sound’s old-growth trees.

“If you cut down a forest, it takes a very long time to come back,” Sizemore says. “So you need to be very careful with the harvest rate.”

Puget Sound has hundreds of millions of geoducks, a seemingly endless supply. But each time a geoduck bed is harvested, it takes about 40 years for the population there to recover. That’s why the total allowable harvest rate is 2.7 percent — anything higher would not be sustainable.

What's the impact of overharvest?

“Ten percent sounds like a pretty low number, but for a very long-lived animal with very low natural mortality, 10 percent is huge,” Sizemore says. “In 10 years, you would wipe out the population.”

Special Report

There's more in our series about poachers, traffickers, and the fight to stop their crimes against nature.

In addition to studying geoducks in the lab, Sizemore's team of five divers check on geoduck beds in Puget Sound and the Strait of Juan de Fuca. They dive 150 times per year, but they're only able to visit about 3 percent of the geoduck harvest areas.

"Our ability to detect [poaching] is pretty low. But even given that, we still see signs of illegal harvest," Sizemore says.

The WDFW divers return to geoduck beds about every 10 years to check on how the population is recovering. Normally they would see geoduck numbers increasing. But in recent years, they've seen numbers staying the same or continuing to fall. And they've also seen signs of poaching: a sandy seafloor pock-marked by recent digs and littered with bright white fragments of geoduck shells.

Poachers have been known to leave bags of geoduck clams on the seafloor to retrieve later. Sometimes they hide their bounty in the hulls of their boats. Or they dive in the middle of the night in secluded coves where there’s little chance of being caught.

Airport inspection

For all the challenges of catching people selling illegal shellfish to customers in Washington, there’s another challenge: Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

Officer Natalie Vorous unpacks boxes of geoduck at Sea-Tac searching for evidence they were harvested legally. These were not. They were confiscated.

Katie Campbell, KCTS9/EarthFix

On any given night, tons of fresh seafood pass through Sea-Tac. It’s a bottleneck and most of the seafood is geoduck packed with gel ice in plastic foam containers.

A geoduck clam harvested illegally from Puget Sound in the afternoon could be on a plane that evening, leaving only a few hours for enforcement officers to get involved. That’s why Sgt. Olson takes his entire five-officer detachment to conduct airport inspections.

When Olson’s team arrives at Sea-Tac one evening, hundreds of boxes labeled “Live Seafood” are already waiting. It’s a race against the clock, and all the checking — each box, each certification tag — must be done by hand.

WATCH: An airport shellfish inspection

They dig in -- opening boxes and cross-checking the information on the tags with online databases to make sure the harvest grounds were indeed open. It quickly becomes clear they won't be able to check all the boxes before time runs out.

"If you hold up [a shipment], and it misses its flight and gets spoiled, our department is on the hook," Olson says. "And there had better be a violation. I'm not going to stop something just because I have a hunch. If I can't confirm information right now, then I've got to let it go."

Olson says a more sophisticated electronic shellfish tracking system would allow his team to scan a barcode to see exactly who harvested the shellfish and from where. A system like that, he says, would make it more difficult to cheat. But many in the farmed shellfish industry have balked at the idea of an electronic system, saying it would be cost-prohibitive for their businesses.

"People are going to take advantage of the holes in the system," Olson says. "And right now there are holes that you can drive a semi-truck through."

Soon an officer finds a box that has no certification tag at all. Then there's another. And another.

"If shellfish is not accompanied by a department of health certification tag, I am required to seize that," Olson says.

WATCH: What Happens To Confiscated Shellfish

Olson notifies airport officials those boxes won't be going abroad. After five hours of spot checking the towers of white boxes, Olson realizes they're out of time.

"This is overwhelming," Olson says. "It's an unrealistic task."

He gathers his team and leaves for the night, taking with him a few boxes of confiscated geoduck. But much more will go unchecked this night -- several tons. The hangar pulses with activity as workers load box after box onto planes bound for Asia.