Mile upon mile of golden stubble — the remains of this summer’s wheat harvest — surround this tiny town in the high plains of north-central Oregon. The soft white wheat grown by nearly 900 area farmers is the region’s economic engine.

That engine would soon sputter without Mid Columbia Producers Co-op. After harvest, the co-op steps in as the key connection between local growers and the global marketplace. Mid Columbia buys, stores and eventually sells the 12 million to 20 million bushels produced annually by its member growers.

This obscure and largely apolitical company finds itself near the center of the stormy debate over Measure 97, the initiative on this fall's ballot that would dramatically overhaul Oregon's tax structure and bring in a colossal $3 billion a year to state government.

Proponents say proceeds from the new tax would end years of chronic shortfalls and funnel much-needed money to schools, seniors and social services. The new money would come from a corporate sector that is undertaxed relative to other states, they argue.

But Mid Columbia executives say their company would be crippled by the gross receipts tax created by Measure 97, a 2.5 percent levy on all sales in Oregon over $25 million. Had the tax been in place in 2015, the company would have paid the state $1.8 million, instead of just $100,000. Rather than posting an annual profit of $1.5 million, the co-op would have tumbled into the red.

Mid Columbia opened its books to The Oregonian/OregonLive and Oregon Public Broadcasting last month — one of the few businesses willing to do so — offering one of the most detailed looks yet at how the measure would affect businesses across the state.

While much about the tax remains in dispute, this much is clear: If you happen to be a grocer, car dealer, wholesaler or some other business that sells in high volumes at a low profit margin, the measure could be extremely painful. Businesses say they will pass along higher costs to their customers to the extent they can. Some may have to take more extreme steps to survive.

“If this measure passes, it will bring our company to its knees,” said Jill Harrison, Mid Columbia’s chief financial officer. “There is zero chance we can afford these kinds of taxes.”

Corporate Oregon’s Declining Contribution

The November ballot initiative would be the largest tax hike in Oregon history. It would be levied only against companies organized as C corporations, as opposed to the more common limited liability companies and S corporations. More than 900 companies would pay the new tax.

Proponents say large companies — those with $100 million or more in annual sales — will provide 85 percent of the Measure 97 money. Moreover, backers argue Measure 97 would finally right a tax system that has swung wildly out of balance. By some measures, Oregon ranks last or nearly last in the country in terms of total tax revenue contributed by business.

Jeff Kaser and Jill Harrison of Mid Columbia Producers say the tax increase from Measure 97 would devastate their business.

Amanda Peacher / OPB

Chuck Sheketoff, a vocal critic of what he calls Oregon’s tax giveaways, points out that 40 years ago, corporate Oregon contributed 18.5 percent of the state’s total income tax collections. Individuals paid the other 82.5 percent. By 2015–17, businesses’ share was just 6.6 percent, a nearly two-thirds reduction.

Sheketoff’s numbers were confirmed by the nonpartisan Oregon Legislative Revenue Office, whose analysis has been cited by both sides of the campaign.

Corporate Oregon’s declining contribution is due at least in part to what Portland investment adviser Bill Parish called “the explosion of accounting gimmicks and tax schemes devised by math Ph.Ds” that corporations use to manipulate their bottom lines and dodge taxes.

“Measure 97 is a beautiful tax because by taxing gross sales above $25 million it ensures taxes will be collected,” Parish said.

Rick Miller, chairman of the Avamere Group, a large chain of retirement living and skilled nursing homes based in Wilsonville, argues members of the business community should pay their “fair share.”

Miller has donated $50,000 to the pro-Measure 97 campaign. Both Avamere and Miller’s current venture — Rogue Venture Partners — are limited liability companies and would not be subject to the new tax, he said.

“No one wants to see business harmed by this thing,” Miller said. “But we need more revenue. In my opinion, this represents the most fair and balanced revenue measure that Oregonians are likely to pass.”

An Impact On High-Volume, Low-Margin Businesses

But the business community’s counterattack has been fierce, claiming the proposed tax is too large, poorly designed and unfair. Opponents dub Measure 97 a “stealth sales tax,” and claim business will pass along as much of the additional cost it can to their customers. In some cases, they say, that would include businesses farther down the supply chain.

Economists Robert Whelan and John Tapogna, both of ECONorthwest, used Oregon Department of Revenue numbers to figure the measure’s impact had it been in place in 2013. They concluded that the larger C corporations subject to the tax would have paid $2.7 billion, equal to nearly half their $5.5 billion in total profits.

“That would have equaled 49.56 percent of their Oregon taxable income — a rate that is more than four times the highest state corporate income tax rate in 2016.” Whelan and Tapogna wrote. Currently, Oregon’s top corporate income tax rate is 7.6 percent.

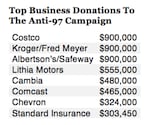

The business community has raised more than $17 million to combat the tax measure, according to state reports as of Oct. 5. The three largest contributors as of Oct. 11 were all giant grocers, Costco, Kroger/Fred Meyer and Albertson's/Safeway, at $900,000 apiece.

Like Mid Columbia, all are high-volume, low-margin businesses of the sort particularly hard hit by a gross receipts tax.

John McKay, chief operating officer of Costco’s northern division, declined to divulge what the company pays in Oregon taxes or what it would pay under Measure 97. But if Costco’s 10 Oregon stores meet the company average of $164 million in annual sales, the Costco stores collectively would face a new tax of $41 million a year.

“Our operating profit is right at about 2.5 percent,” McKay said. “Our Oregon operations would be operating at a loss. We would have to accept that or pass along the increase to our customers, neither of which we want to do.”

The grocery sector also illustrates the tax’s selective nature. Costco and Fred Meyer, for example, would pay the new tax as both are C corporations. Safeway, New Seasons and Winco are structured differently and would not pay.

Founders of new businesses can commonly incorporate their new ventures as C corporations, S corporations or limited liability companies. Each is subject to somewhat different tax treatment. As of August, Oregon had more than 170,000 limited liability companies and 78,498 business corporations (both C and S,) according to the Oregon Secretary of State’s office.

Only 951 C corporations are large enough, with more than $25 million in Oregon sales, to qualify for the new tax.

Related: Measure 97: How We Got Here

Proponents of Measure 97 concentrate on the big, unpopular national corporations that would pay a hefty share of the tax. Think Wells Fargo and Comcast. Oregon boasts 274 C corporations that generate $100 million or more in annual state revenue. Those mega-companies would shoulder 66 percent of the new tax obligation, according to the Legislative Revenue Office.

The largest companies’ share of total corporate taxes would jump from 46 to 79 percent.

But it’s not just multinational corporate giants on the hook. The state Office of Economic Analysis estimates that about 18 percent of the new money would come from Oregon companies, some of which claim the new tax could put them out of business.

Jan Yost heads DSU Peterbilt & GMC, a heavy truck dealer with dealerships stretching from Medford to Kelso, Wash. It employs 232 people. Like executives at Mid Columbia, Yost was willing to divulge his company’s key financial numbers to better illustrate Measure 97’s impact.

DSU brought in $153.4 million in sales in 2015, $128.4 million of which would be subject to the new tax. DSU paid $262,200 in income taxes last year, leaving an after-tax profit of $243,642.

By Yost’s reckoning, had the gross receipts tax been in place, DSU’s 2015 taxes would have soared past $3.2 million, wiping out his profits and pushing DSU far into the red for the year.

Yost said he’s considered moving the corporate headquarters to Washington. But he concluded it wouldn’t do much good because most of his sales would still take place in Oregon.

Related: Gov. Kate Brown: Consumers Would Pay Part Of Corporate Tax Increase Cost

He’s also considered changing his corporate structure to become an S corporation or a limited liability company, which are not subject to the tax. But that takes time and money. Converting from a C corporation to an LLC comes with its own tax hit. Both the IRS and the Oregon Revenue Department consider an LLC conversion a taxable event, both at the corporate and shareholder level.

“In some cases, the tax can be more than half the value of the company,” said Christopher Heuer, a tax lawyer with Stoel Rives.

Raising prices to customers in the highly competitive auto sales business also would be difficult, he said.

“This new tax would put us instantly in the red,” Yost said. “My dad founded this business in 1945 and we built it up to what it is. This new tax will tear it right down. Those 232 people will be out of work.”

Oregon’s technology industry is uncharacteristically joining the political fray. Through a quirk of existing law, the Measure 97 tax would apparently work differently for Oregon-based software companies and other service-sector operations. Most of those companies would be taxed on all of their sales over $25 million, whether they take place in Oregon or not.

“It’s not like we’re not in favor of tax reform,” said Diane Fraiman, of Voyager Capital. “We agree we need more money for schools. But this is not the way to do it. This could really hurt the existing companies that we’ve worked so hard to grow over the last decade. And for anyone thinking about moving here, they’ll go elsewhere.”

Gov. Kate Brown and lawmakers have talked about addressing the software problem and other issues in next year’s Legislative session. Critics of the tax, noting Brown’s enthusiastic support, are not reassured any significant tweaks are forthcoming.

'We Are Anything But A Big Evil Corporation'

Meanwhile, in faraway Moro, Mid Columbia executives mull over their options.

Ironically, the company wouldn’t have a stake in the Measure 97 fight if it was just a grain co-op. Its grain-related revenue is not subject to the tax because it involves only co-op members, said Jeff Kaser, co-op general manager.

Related: Measure 97, PERS Divide Candidates For Oregon Treasurer, Secretary Of State

But to lessen its exposure to the volatile swings of the wheat business, Mid Columbia diversified. It opened three retail hardware stores in nearby small towns, it operates a seed plant that sells wheat seed to farmers, and it purchased a chain of gas stations from Goldendale, Washington, south to Chemult.

The gas station business is competitive and low-margin. But it’s become Mid Columbia’s second largest business behind grain, generating $54.3 million in sales in the company’s 2016 fiscal year. Unlike wheat, the gas, seed and retail revenue would be subject to the gross receipts tax.

Instead of the $164,000 it paid in 2016 state income taxes, Mid Columbia would have paid more than $1.1 million if Measure 97’s tax were in place. The tax would have eaten most of Mid Columbia’s $1.5 million in profit.

Had the tax been in place in 2015, Mid Columbia’s $100,000 state income tax would have been replaced by a $1.8 million gross receipts tax bill, an 18-fold increase that would have pushed Mid Columbia into the red for the year.

Like Yost and his truck dealership, Kaser can’t see an easy alternative. Moving across the Columbia River wouldn’t appreciably reduce the company’s tax bill. With 800 members, it has far too many owners to convert to an S corporation.

[image: 201609_ap_Mid Columbia_hohensee-1b,left,image-full,57fc230eeeac35007117f8d0]

Kaser argues that raising prices isn’t a viable option. It will simply drive customers to competing gas stations. He hopes to avoid cutting the company’s 62-person payroll.

One thing Mid Columbia has done is to join the fight over Measure 97. The company came out against the tax, as did the Sherman County Board of Commissioners.

“We’re not political, this is the first time we’ve gotten involved in something like this,” Kaser said. “We are anything but a big evil corporation. We’re here for our members. We’re all for good schools and strong education. But this is threatening our future.”

Miller, the pro-97 executive, counters that businesses will be able to adjust to the new reality.

“I understand their criticism. We are talking about corporations paying a good deal more,” he said. “But contrary to a lot of the negative rhetoric, Measure 97 really offers an opportunity to make a generational difference. If we do it the right way, I think we can improve the investment climate.”