About two dozen high school students and parents walked around around Concordia University in Northeast Portland on a recent warm morning. They were on the kind of tour that colleges have done for years, where teenagers and their families poke their heads into dorm rooms and laboratories and hear from professors and students.

Leslie Velasquez, a high school senior in College Place, Washington, had already visited four or five colleges across the Northwest when she arrived at Concordia.

“I’ve gone to some universities where the dorm rooms are pretty small, and I wonder if I have space to study, and quiet, I guess,” Velasquez said.

“Atmosphere,” “dining” and “dorms” will be key, she said, as she chooses where to go to college. Especially, food.

“If I’m going to study at a university, I’d like to have more food options,” she said.

Students have prioritized food quality, room size and the look and feel of a campus probably as long as there have been residential colleges and universities. And those priorities remain, even as college admissions has grown more competitive and harder to predict.

“Right now, my top ones are Eastern Washington and Pacific,” Velasquez said on her visit to Concordia. But she was quick to add that she was still planning to visit the University of Portland and Linfield College before heading home.

Berta Velasquez, left, and her daughter Leslie Velasquez of College Place, Wash., in the library at Concordia University in Portland, Ore., Tuesday, July 30, 2019.

Rob Manning / OPB

College shopping has gotten easier over the last decade, as more information is online, and more colleges have started accepting a universal application. Use of the Common Application hit a record this year with 5.5 million applications, according to the nonprofit Common App.

But a recent study by the Pew Research Center found that the rise in applications isn’t unique to the rising interest in the “common app.”

“Although one might suspect that the ease of applying to multiple schools via the Common App would result in stronger growth in application volume among those schools, there was almost no difference in 2002-2017 growth rates between the schools that used the Common App and those that didn’t,” Pew researchers concluded in a study earlier this year.

Related: The American West's Oldest University Struggles To Find A Future

The high number of college applications persists, despite a diminishing number of typical college applicants in the 18- to 24-year-old range. That means college counselors are sifting through a greater number of applications from students who are likely considering more colleges than in the past. So colleges and universities are fishing in a shrinking pool of students, even as those students are being increasingly choosy about where they might enroll.

They’re still concerned about the dorms and dining — but they’re also increasingly focused on what they’re going to college to learn. The only way Concordia University got onto Leslie Velasquez’s radar, so that she could judge its dorm rooms and dining fare for herself, was by offering a business program.

“I'm looking for something in business. Mostly business administration, like controlling a business,” Velasquez said.

Higher education itself is a business, with high school students and their parents as customers. But while the customer base is shrinking, costs are rising. Passing on those costs to families is not a great solution.

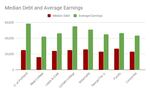

University of Portland and Linfield College boast the highest median earnings for recent graduates of Oregon's larger private colleges, while Reed College claims the lowest student debt loads.

National Center for Education Statistics / US Department of Education

The college experience — perks such as room size and food quality — have always mattered to students. And colleges have spent millions on rock-climbing walls, lazy rivers and student center expansions. But that trend has cooled recently, in part because students themselves have said no by voting against raising fees to pay for such amenities.

Rather than looking for the most extravagant campus experience, students and families are looking more carefully at costs, debt loads and potential career earnings.

Kelly Wilkins and her two daughters were in the same tour group as Leslie Velasquez and her mom. Both the Wilkins daughters are interested in careers in health care, and they came to Concordia armed with research about the college. Meadow Wilkins is interested in following her mother into nursing, but she and her mom worried about Concordia’s limited number of openings in the nursing program between sophomore and junior years.

“She wants to apply to nursing,” Kelly Wilkins said. “We want to make sure that if she’s putting in two years of her time and education money, she has a spot.”

“I don’t want to have to switch my major either,” Meadow chimed in.

Concordia psychology professor Reed Mueller often meets families when they tour the campus. He was the first to field the Wilkins’ family questions.

“With the cost of education families are considering the endpoint there,” he said later. While acknowledging he hasn’t “done any formal research on it” Mueller said he’s heard certain questions more and more in the eight years since he joined the faculty.

“I have noticed … this shift more toward a career path: ‘Where might I end up with this degree? How might this degree help me enter into the workforce in a viable way?’” Mueller said.

Concordia’s approach to those questions seems to be working.

A guide leads a tour for prospective students at Concordia University in Portland, Ore., Tuesday, July 30, 2019.

Rob Manning / OPB

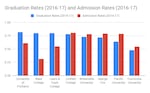

The tendency of students shopping around more in recent years is evident among Oregon’s private colleges: Most of the larger schools have seen slight declines over the last four years in the share of students accepted who end up enrolling. The notable exception is Concordia, which has gone from enrolling 16% to 18% of its accepted students.

The college grew by well over 400 undergraduate students last year.

Concordia officials say the expansion is consistent with the university’s strategic plan, which includes growing enrollment as one of its top priorities. The plan discusses finding a balance between a liberal arts foundation and career-focused programs such as nursing, business and teacher training. Concordia is also reaching out to traditional high school graduates planning to live on campus and a variety of students who could take courses online.

Concordia stands out among Oregon private colleges for involving nearly one-third of its undergraduates in online courses. Concordia students also have lower average standardized test scores than Oregon’s other private colleges. Its students are less likely to graduate within six years and have lower post-graduation earnings than most of their comparable institutions.

Of Oregon's eight largest private colleges and universities, University of Portland had the highest graduation rate, in 2017. Concordia had the lowest.

National Center for Education Statistics / US Department of Education

Near the end of the Concordia tour families hear from the college pastor, Father Bo Baumeister.

It was a reminder that college can be more than a career platform, an academic pursuit, or a chance to indulge in living away from home. It can also be a four-year opportunity for young people to explore or question their religious or political values.

That goes for career-minded students, like Meadow Wilkins.

Related: Linfield College Faces Division, Debate As Leaders Attempt To Defy Enrollment Trends

“I like the aspect from the faith point of view that like everyone’s [part of] a community, but I would be open to going to public too,” Meadow Wilkins said.

“I just think we're looking at strong nursing colleges,” her mother, Kelly Wilkins, added. “That's our biggest thing for them — the right fit.”

By “them” Wilkins means Meadow and her sister Zoe.

“My sister wants to do [physical therapy], and we just want to make sure that she is secure too,” Meadow said.

Zoe Wilkins, Kelly Wilkins and Meadow Wilkins following a campus tour of Concordia University in Portland, Ore., Tuesday, July 30, 2019.

Rob Manning / OPB

In the end, all the priorities — from campus to career, personal to professional — get filtered through the brain of a college-bound student, most often a high school student. College recruiters, meanwhile, are trying to keep up with the changing interests of young people, or even stay ahead, so they can focus their time (and money) on recruiting students who genuinely want to attend their schools.

With increasingly cost- and career-conscious families, fewer college-going students and tighter margins on college campuses, admissions offices face a complicated and competitive situation. Cautionary tales abound, with names like Marylhurst, Trinity Lutheran and Oregon College of Art and Craft — Pacific Northwest schools that no longer exist.