For Cristi Martin, the question that breaks her heart each day is, why? Why did police shoot and kill her son Lane?

Lane Martin and his mom, Cristi Martin

Courtesy of the Martin family

Cristi lives in Reno, Nevada, with a husky puppy. She has a blonde bob and blunt bangs.

On July 31, she was hoping Lane would call. He was turning 32. He never failed to send her a handmade card for mothers’ day and he usually called on his birthday.

Instead she got a voicemail from the Portland police.

“When I called them back, they said, 'Are you anywhere near your son’s house? Can you please go to your son’s house, and then we will, and then we’ll talk.' And then I knew, right then and there … I knew,” Cristi said.

Lane Martin was the fourth person killed by Portland police this year. In many ways he's typical of who dies in police shootings in this city: He was armed with a small folding knife. He wasn't following orders. And, his mom, Cristi, said, he had a mental illness.

“I’m sure that he looked like he was some homeless crazy person, and he wasn’t," she said, suggesting that's not a fair way to look at anyone. "You look at people wandering around the street, and you think, they’re just crazy. But they’re somebody’s family.”

The knife police found under Lane Martin's body.

Portland Police Bureau

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Justice conducted a year-long investigation into the Portland Police after a series of high profile deaths of people in a mental health crisis.

On Dec. 17, 2012, the city signed a settlement agreement with the DOJ. It spelled out how the Police Bureau would improve training and supervision for its officers to reduce unnecessary uses of force.

The DOJ investigation had two key findings. First, police officers were using excessive force – including deadly force — against people with mental illnesses.

Second, Oregon’s mental health care system was so profoundly broken that police were often the first, or the only responders in a crisis.

In a city that’s supposed to be working on solutions to both of these problems, Lane’s death is an illustration of how far it still has to go.

Struggles With Mental Illness

Lane had a record of addiction, jail time and mental illness. In his 20s, doctors suspected he had bipolar disorder, though his mom said Lane rejected that diagnosis.

Lane Martin at his Portland Community College Graduation.

Courtesy of the Martin family

In recent years, Cristi said Lane was proud of being healthy and in recovery.

“He was doing so well that we thought that was kind of behind him,” she said.

Lane Martin lived in a small apartment in East Portland. He’d earned his associates degree. He was studying fine art at Portland State University and had a job in the facilities department there. His classmates described him as the kind of enthusiastic student who would sit in the front row and ask lots of questions.

He loved the outdoors and drove a 2017 Subaru.

Then, last June Cristi got a call from her son’s girlfriend. Lane hadn’t slept and was acting strange. Cristi flew to Portland.

“He was very paranoid about other people. At one point, we’d gone for a walk. He’d started taking pictures of random people walking by, said he felt like they were threatening him,” Cristi said.

Lane started recording his conversations with Cristi. She worried he was having a psychotic break.

If our system worked better, this is when Lane might have gotten the help he needed.

His mom and his girlfriend took him to see doctors who prescribed Seroquel, an anti-psychotic medication. His cousin, a psychiatric nurse at the Oregon State Hospital, gave the family advice.

A text message Lane Martin sent his family before checking himself out of a Portland psychiatric emergency room.

Courtesy of Lori Martin

But Lane never grasped that he was acting differently, which can be a symptom of some mental illnesses. His family said that made it virtually impossible to get him consistent care, because of policies in Oregon that protect people from being committed against their wishes.

After a particularly bad night, police officers and Project Respond, a mental health crisis team, came to Lane's apartment.

They took him to the Unity Center, Portland’s psychiatric emergency room. He was held there for 72 hours. Before he checked himself out, Lane texted his family.

“I’m doing the best I can,” he wrote. “Love you guys.”

An Unclear Picture

Cristi doesn’t really know how he spent the next four weeks.

The Portland Police Bureau isn't answering questions about Lane's death, but they have released 500 pages of records from their investigation.

On July 30, according to police records, Lane threatened a security guard in the parking lot of an abandoned Safeway in East Portland.

He claimed he was a federal officer and pulled out a knife and a hatchet. Police followed him as he walked and ran through traffic and into an apartment complex. He dropped the hatchet after police shot him with sponge-tipped bullets.

What happened next is a little unclear.

Two officers who witnessed the shooting said Lane had reached to his waistband. A third witness officer said she saw a knife in is hand.

Related: Grand Jury Clears Portland Police Officer Who Killed PSU Student In July

Officer Gary Doran fired his gun 11 times, according to police detectives — 12 times, according to the family's attorney.

There aren't any statements from Doran in the documents the Portland Police Bureau has made public.

Officers found a 3-inch folding knife attached to a set of keys underneath Lane's body.

This week, a grand jury concluded that the shooting was justified as an act of self-defense or defense of the public.

Lane's family disagrees. This week, they sued the city and Doran.

Stopping A Pattern

The suit alleges that the pattern of police using excessive force against people with mental illnesses in Portland hasn’t changed.

Data presented in the lawsuit, and in official reviews of recent officer-involved shootings, suggest that between one-third and one-half of the people the Portland Police shoot have a history of mental illness or are in a crisis.

“That’s not an usual scenario, unfortunately,” said Mike Genaco, an expert on police practices and founder of the OIR group, a firm that reviews officer-involved shootings for Portland.

Genaco said each fatal shooting is a tragedy — but also a chance for the Portland Police Bureau to learn from what went wrong, and to improve its officers' training.

"In that particular arena, more definitely can be done," he said.

Genaco thinks the bureau is sometimes too hesitant to be critical of officers' performance after a shooting.

But he also said the public should understand that fatal shootings represent a tiny percent of police interactions with people who are mentally ill.

He said the bureau’s training is getting better. More officers are learning how to deescalate situations, instead of resorting to force.

What the data doesn’t reflect, he said, is how many times officers have used their training to avoid a deadly confrontation. It's hard to quantify that.

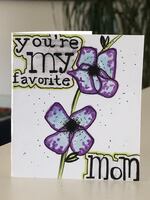

A card Lane Martin sent his mom, Christi, in 2019.

Courtesy of Cristi Martin

“That’s what makes me optimistic,” he said. "Where an officer who did go though critical incident or crisis intervention training was able to diffuse a situation."

Cristi doesn't understand why Doran shot her son, but she said she has a lot of respect for the work police do.

"They put their lives on the line every day. I understand that,” she said.

Cristi is still trying to figure out what would have kept her son alive. Better training for the police? Consequences for officers who use excessive force? More compassion for people who have a mental illness?

She’s not sure.

She just knows she doesn’t want it to happen again, to anyone.