A little over a month ago, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown gave child care centers a choice: continue to operate with a focus on the children of “essential workers,” or shut your doors.

Nancy Golden watches two Earl Boyles Elementary School preschoolers.

Michael Clapp / OPB

Nearly half closed.

That's actually not as bad as national trends, according to a recent survey by the Bipartisan Policy Center and Morning Consult, which found 60% of daycare centers "are fully closed and not providing care to any children at the moment."

In Oregon, 1,700 of the state’s roughly 4,000 licensed child care centers are closed. Certainly, many childcare workers have lost their jobs, but the Oregon Employment Department doesn’t have numbers on how many.

“We do not have that level of detail,” OED senior economic analyst Anna Johnson told OPB in an email.

According to an Employment Department article, childcare workers are included in a broad “Other Services” category, which is responsible for roughly 12% of the state’s jobless claims from late March to late April.

That category, which also includes hair stylists and massage therapists, is responsible for the third-largest share of jobless claims, after the hospitality and entertainment sectors. Brown has issued 17 executive orders to restrict business and social activity over the last two months.

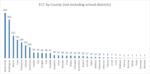

Oregon Early Learning Division has approved at least one "emergency childcare provider" in every county in the state.

Oregon Early Learning Division

State officials are praising providers that have continued to operate: 2,085 centers have adjusted to a new set of rules and begun focusing on “emergency” care for children of essential workers.

Centers operating under those new rules are required to follow a 20-page "Emergency Child Care Guide For Temporary Child Care Facilities." It includes tighter child-adult ratios, special screening procedures for potentially ill children, as well as maintaining the same group of children from day to day "to the extent practical."

The pandemic has been a difficult and uncertain ride for parents of small children, as well as for the preschool teachers and daycare staff who care for them. On March 17, when Brown declared that public schools would stay closed through April 28, she kept child care centers open. She directed three state agencies to “collaborate and align resources to support and ensure the reimbursement for, continuity of, and availability of care provided by family-based, center-based, and license-exempt child care providers.”

Over the next week, COVID-19 case numbers continued to grow; the total went from 65 cases on March 17 to 161 when she issued her “Stay Home, Save Lives” order six days later.

Her approach to child care also changed March 23, when she called on parents with jobs deemed non-essential to care for their own children, and for child care centers to prioritize slots for critical workers — doctors and nurses, police officers, among others. That is, if they were going to keep operating.

The Early Learning Division’s 2,085 emergency centers include 29 new providers, which were not fully licensed as care facilities before the pandemic. ELD communications director Melanie Mesaros said most of the “new” programs had previously been authorized as short-term “recorded” rather than licensed care centers. In addition, 44 school districts have been allowed to provide care, but the state hasn’t been actively tracking which ones are actually caring for children.

“At this time, we are not aware of any part of the state where there isn’t enough supply of child care,” Mesaros said in an email, noting that there are 8,000 open slots across the “emergency child care providers.”

But elected officials and national policy experts warn that there could be lasting damage from the pandemic-related loss of nearly half the state's child care centers. In part, that's because all 36 counties in Oregon were identified as "child care deserts" in an OSU study released last year.

“The lack of quality, affordable child care options in Oregon unfortunately is not a new challenge,” U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Oregon, said in a statement last week. “Well before the pandemic, Oregon was a ‘child care desert’ and those serious concerns are now magnified with the uncertainty unleashed by the coronavirus outbreak.”

Oregon received $38 million in CARES Act funding for child care, but members of the state’s Congressional delegation say it’s insufficient to help providers through the COVID-19 crisis.

“Child care businesses operate on razor-thin margins, and without significant support many of them won’t make it to the other side of the pandemic,” said U.S. Rep. Suzanne Bonamici, D-Beaverton.

An analysis released April 24 by the liberal-leaning Center for American Progress concluded that 48% of Oregon’s child care slots — or nearly 45,000 openings — could disappear permanently without more federal assistance. That analysis suggests that Oregon will see even more closures than the 42% of child care centers that have already shut their doors this spring.

Much like other types of businesses, whether child care centers can return may depend on how long they have to remain closed. Child care is part of Brown's complicated "Reopening Oregon Framework," currently a draft being workshopped in meetings with various economic sectors.

Just as child care was a challenge as Brown tightened regulations over the last two months, reopening centers could be a tricky balance, as well — involving public health priorities, workforce demands as well as the capacities and financial constraints of the centers themselves. Brown’s framework includes “additional child care reopening in Phase One” – meaning rules could be relaxed as the state hits its initial targets regarding disease symptoms, case numbers and hospital capacity.

But first, state officials are trying to learn more about what’s preventing child care centers that have closed from operating as emergency child centers, as allowed under Brown’s previous executive orders. ELD officials said they extended a survey intended to close last week, so that unions and advocacy groups could share it more widely through their networks.

“It’s important for child care providers to weigh in on what they need to operate safely as the governor’s office will be using feedback to inform reopening plans,” read a statement on the web site for the Portland-based Children’s Institute, linking to a survey the state is circulating to providers.

The 15-question survey asks providers that have closed what the barriers are to running under the emergency rules, as well as their view on specific rules – such as frequent sanitizing of surfaces and toys, and taking children's temperatures.

But the survey also nods to the complex, interconnected challenge for providers. It asks how important the reopening of other businesses will be to re-enroll children and whether providers worry they may have children to care for, but not the staff to hire. That’s another problem that plagued Oregon’s childcare industry before the pandemic.