Christine started applying to become a foster mom after watching family members take in children.

She only wants to use her first name because she doesn’t want to scupper her chances with the Child Welfare division of Oregon's Department of Human Services.

Christine has a good job, a three-bedroom house and no kids.

“If people like me don’t do it, who’s going to do it?” she asked.

So she took a foundation course and let the state do a home inspection.

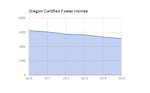

Oregon Department of Health and Human Services

It’s been six months now, and she still hasn’t been verified.

Christine has lived in three states. Along the way, she's had three background checks. One of which, she says, the Department of Human Services lost them and then found them again.

Also, the agency asked for her entire medical history. She’s a lawyer and wanted to limit it to a report from her doctor on her mental health and her prescription history.

She was called in for a meeting. “The supervisor was very defensive, saying the point is that 'We asked you for it.' And I said my point is that you need to tell me why you need it. And she said: 'Well, I would have to review your file.' And my certifier was sitting right there with my file, so I said: 'Could you just look at it?' And so eventually she looked at it and she said: 'Oh, we don’t need it. But if you ever want to adopt, we’re going to need your medical history.' Okay. I’m not looking to adopt right now.”

Christine says she understands the need for an extensive background check, but the entire experience has left her frustrated.

“My complaint is that you have people who are trying to help and the message I got is that you’re bothering us. You’re not following our directives, you’re not playing by our rules. We don’t have to justify anything to you,” she said.

A DHS spokeswoman asked that families be patient, saying staff are working hard to make sure children are placed in safe homes.

As someone who went through foster care as a child, Joni Thurber wanted to offer her home to a 16-year-old. The boy was placed before she got through the application process. But she says the $575 a month stipend seemed woefully insufficient.

Kristian Foden-Vencil/OPB

Joni Thurber is another person willing to open her home to a foster child. She’s a secretary at a Portland-area school district.

She recently learned about a 16-year-old in her district who was in temporary need of a place to live.

Having been in foster care herself, she contacted DHS to help. The boy was placed before she got through the application process, but she says the $575 monthly stipend seemed woefully insufficient.

“The compensation just blew me away," she said. "They’re asking somebody to take on a child who’s a stranger in their home, a risk in their home, not only to their property, but to their other family members. And I don’t mean to say 'they,' I mean we as a society just are not valuing the responsibility it takes to raise a child.”

Thurber works full-time and says she wasn’t even offered a bus pass for the boy to travel to medical appointments.

Speaking on OPB’s Think Out Loud, Reginald Richardson with Oregon’s Department of Human Services, says he’s heard the complaints and is looking into them.

But he said his priority is the 6,000 unfinished investigations of abuse and neglect that were on the agency’s books when he started last year.

“That may mean that what some of our district managers may be doing is deploying staff from certifying foster parents or applicants to the front end of the system to ensure that we’re completing the assessment process,” he said.

Richardson also agreed that the financial burden of being a foster family is high.

“So the cost of having a child in your home, continues to grow, while the reimbursement rate doesn’t. We also don’t provide day care, although working on being able to do that. So I think there are things that we need to do to support the foster family that would help them to stay as a part of our team,” Richardson said.

He said the agency is talking to legislators about more financial help.

State Sen. Sara Gelser chairs a Committee on Human Services and Early Childhood. She told OPB that she’s heard from many people who’d like to help a child but are hindered by barriers.