Steve and Sandy Swanson were in a festive mood. It was an early December day and their house was ready for Christmas.

“We already had our Christmas tree up,” Swanson remembers. “The house looked beautiful.”

But, then, a representative of the Navy knocked on the door of their home on top of a ridge on Whidbey Island,

“She walked in, and she seemed genuinely moved by the bad news she was going to have to tell us,” Swanson says.

The Swansons' Whidbey Island home overlooks Admiralty Bay.

Eilis O'Neill, KUOW / EarthFix

The bad news was that the Swansons' well is contaminated. It has six times the Environmental Protection Agency's health advisory level of what are called perfluorinated chemicals. These are chemicals that have been linked to cancer, thyroid and liver problems, and low birth weight and other developmental problems. A 2009 study by the Washington Department of Ecology found these chemicals in waterways and wildlife in the Pacific Northwest--but the state's plan to deal with the problem is six years behind schedule.

The moment the Swansons learned about their well water, they stopped drinking it. That was six months ago. They also decided not to plant their vegetable garden this year because they wouldn’t be able to irrigate it.

“We have a system of how we, you know, wash our produce, brush our teeth,” Sandy Swanson says. “It's a pain.”

The toxic chemicals made their way into the Swansons’ well from fire-fighting foams dumped on a naval airstrip less than three miles away.

The Swansons and their neighbors aren't the only ones to find their drinking water contaminated this way. Wells near Joint Base Lewis-McChord south of Tacoma and Fairchild Air Force Base outside of Spokane have also been contaminated. The same thing happened to the water supply in Issaquah, which has a fire training facility nearby. And the EPA and military have identified other contaminated sites across the country.

Firefighting Chemicals Contaminate Water Across Washington

Toxic chemicals used in firefighting foams, non-stick cookware, and textiles have been detected in some of Washington's waterways and groundwater. In particular, they've contaminated some drinking water sources near military bases and fire-training facilities.

Tony Schick and Eilís O'Neil/EarthFix. Sources: U.S Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Navy, U.S. Army, U.S. Air Force.

“The information that we have is really probably just the tip of the iceberg,” says Erika Schreder, with the advocacy organization Toxic-Free Future. That’s because, even though the EPA tested drinking water systems across the country for perfluorinated chemicals, “it was a subset of water systems, and so not everyone’s water has been tested”--and the EPA only flagged results with a certain concentration of contaminants.

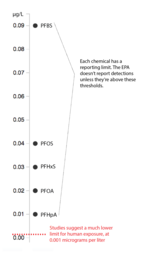

EPA reporting limits could hide unsafe chemical levels

The EPA tests for perfluorinated compounds but it doesn't regulate them. In some places these tests are detecting these compounds at higher levels than some studies suggest is a safe level of exposure.

Tony Schick/EarthFix. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Hu, Cindy et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 2016.

The Navy is doing additional testing near its bases but it’s only testing for two chemicals, not for the six chemicals the EPA looked for. And it’s only testing each well once, even though researchers say contaminant loads can vary widely from season to season. Furthermore, the Navy’s only looking at water systems within one mile of its bases.

That's because those are the only chemicals "that the EPA has established risk information for right now," says Kendra Leibman, a remedial project manager for the Navy. So they're the ones "that the Navy is is volunteering to take action on," she says.

If the EPA establishes health advisories for other perfluorinated chemicals, Leibman adds, "if we don't have that data, ... then we'll have to go back out and sample again."

Erika Schreder with Toxic-Free Future says one way to get all our water tested and cleaned would be to establish a state-level limit. That would help, in part, because the EPA limit is only advisory, while a state limit would be regulatory and would therefore require testing all water systems and then cleaning them up. New York and Vermont have already taken that step and other states are considering it.

EPA reporting limits could hide unsafe chemical levels

The EPA tests for perfluorinated compounds but it doesn't regulate them. In some places these tests are detecting these compounds at higher levels than some studies suggest is a safe level of exposure.

Tony Schick/EarthFix. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Hu, Cindy et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 2016.

What Washington is doing right now is working on a “chemical action plan.” The goal is to deal with all the sources of perfluorinated chemicals: not just fire-fighting foams but carpets, non-stick pans, hamburger wrappers, raincoats, and more. Perfluorinated chemicals won’t stick to other molecules, so they’re helpful not just for putting out oil fires but also for stain-proofing, grease-proofing, and waterproofing.

The committee started back in 2009 by looking at where these chemicals show up in Washington’s water and wildlife, and they found them not just in water but in higher concentrations in fish and even higher concentrations in osprey, birds that eat fish. That indicates that humans who eat fish could also get exposed to these chemicals.

“To see it at these levels in our environment confirmed why we had to prioritize this,” says Holly Davies, the Department of Ecology toxicologist in charge of the committee.

Yet the committee stalled.

“We've had starting and stopping for different reasons, some of which were legislative direction to work on other topics,” Davies explains.

Chemical action plans normally take a year and a half. This one is going on eight, and it will be at least another year before it’s finished, Davies says.

The plan could include restricting the manufacture or import of certain products, mandating a limit for how much of these chemicals can legally be in drinking water, and cleaning up the chemicals where they’ve already been found.

Back on Whidbey Island, the Swansons show off their three-story home and five-acre property. They’ve lived here since 1999.

“This is our dream house,” Sandy Swanson says. “Steve milled all these timbers from our farm on South Whidbey. We have one of the best views on the island. But we need to move on.”

Swanson says she and her husband want out. She’s almost seventy and her husband is seventy-three, and, she says, they don’t have many years left.