Last winter, Linfield College was at a turning point. Student enrollment was dropping and administrators were running out of ways to cut the budget. They’d already frozen salaries, increased tuition and sold off property. Faculty layoffs were on the table.

Melrose Hall at Linfield College is seen through Japanese maple leaves Tuesday, May 21, 2019, in McMinnville, Ore. Budget cuts and declining enrollment have forced tough decisions about the future of small, private colleges like Linfield.

Bradley W. Parks / OPB

“Involuntary separations were a very real possibility,” said Jackson Miller, the dean of faculty at Linfield.

Miller and his colleagues had watched as Linfield shrank from 1,700 students in 2015-16 to 1,376 last year. The college’s tax filings showed a 10% drop in net tuition income, from $44.5 million in 2013 to $40.5 million last year.

Such budget and enrollment declines have preceded major restructuring across the country, including college closures and mergers. Since 2016, close to 90 colleges and universities have closed, merged — or announced they will soon. More than half of those are private colleges.

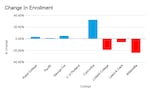

Over the last four years, Linfield College and Willamette University saw the steepest declines in student enrollment.

Common Data Sets, Oregon private colleges, 2014-2018.

In Oregon, that included Marylhurst University in 2018 and the Oregon College of Art and Craft earlier this year. When Marylhurst closed, leaders of the 100-year-old institution said they hadn't moved quickly enough to respond to enrollment declines.

Cutting To Stay Ahead Of Decline

Linfield administrators are hoping they’re making changes quickly enough. On the front lines of those changes is President Miles Davis, entering his second year at the helm of the college in McMinnville.

“We just had to address the issues relevant to how do you balance a budget,” Davis told OPB recently.

Linfield College President Miles Davis is entering his second year at the McMinnville school.

Rob Manning / OPB

By the time Davis arrived, Linfield had already taken a number of cost-cutting measures. In a February 2019 message to the Linfield community, Davis shared a summary of cuts the board of trustees had already approved over the last four years:

- Elimination of administration and staff positions

- Hiring freezes of administration, staff and faculty positions

- No general salary increases for employees

- Reduction in retirement benefits

- Operating budget cuts

- Reduction in capital spending (monies used to maintain and/or upgrade facilities)

- Use of one-time funds; e.g. sales of property

- Tuition increases

- Offering early retirement to qualified employees

The outlook at the time was bleak. While official enrollment listed in the publicly-reported “common data sets” put Linfield’s enrollment at 1,376, the college was planning for an even smaller student body – and changes in response to it.

Related: The American West's Oldest University Struggles To Find A Future

“A part of the College’s restructuring and academic prioritization process will be to eliminate some faculty positions that were consistent in a time when we had more than 1600 students, but are not sustainable in our present circumstances (1240 students),” wrote Davis last February.

Before administrators started writing any pink slips, though, Davis asked for volunteers to leave or retire early.

“We asked our community to chip in, and part of that chipping in came from faculty members and our staff who took either a voluntary early retirement – in the first part of the year — or took a voluntary separation agreement,” Davis said in an interview.

College administrators said the idea for “voluntary” separations came from faculty. But the step made professors anxious. Many had been part of the Linfield community for years and had no plans to leave soon.

“You know, ‘I’m not ready to retire, or close,’” Miller recalled one professor telling him. “‘But I want to take this offer both to help the college and to ensure my junior colleagues, who are just starting out their careers, have an opportunity for a longer career at Linfield.’”

Core Principles At Stake

The possibility of layoffs is scary in any workplace. But in higher education, laying off professors threatens a core principle throughout academia: Tenure.

Professors work for years to earn the job security and academic freedom that comes with tenure. For a college to lay off tenured professors for budget reasons is admitting financial disaster, but that's what Linfield was doing according to faculty familiar with the discussions last winter.

In the winter and early spring, the Linfield chapter of the American Association of University Professors circulated a petition to faculty across the country, asking for help fighting a perceived threat to tenure.

Administration officials insist there was never a serious discussion about eliminating tenure. But Miller said significant changes were certainly debated.

Pioneer Hall is seen through the signature oak trees at Linfield College in McMinnville, Ore., Tuesday, May 21, 2019. Pioneer Hall is the oldest building on the Linfield campus, constructed in 1881.

Bradley W. Parks / OPB

“There were definitely some discussions about that. I think we had some difficult internal dialogues about that, that went through the faculty and even to some limited discussions at the board of trustees level,” Miller said.

“But I think the positive result of all of that is, from trustees on down, a real sense of recommitment to tenure.”

Ultimately, the college saved enough through other cuts, such as early retirements, to avoid faculty layoffs.

But tenure wasn’t the only core principle at stake. Faculty complained that the approach to the budget problems was not collaborative, and inconsistent with Linfield’s commitments toward “shared governance” with the faculty.

Related: Thinking Of Becoming A Linfield Wildcat? Your Cat Can, Too

Administrators, such as Davis, decided which voluntary separations and early retirements would be accepted. Professors say those decisions raised questions about the college’s commitment to its core mission: liberal arts education.

As a private college, Linfield administrators don’t have to share internal details of budget decisions, and they declined to discuss specifics about which separations and retirements were accepted. Miller analyzed them and said that more separations came from arts and humanities, followed by social sciences and hard sciences with the fewest.

Signs Of Growth

There’s one program that was spared any cuts through retirements and separations: nursing. Demand for the nursing school is growing, and the college is feeling pressure to hold on to, or expand its faculty, rather than shrink it to save money.

“If anything, we’ve had more applicants than we can take,” said Paul Smith, associate dean of Linfield’s School of Nursing.

Associate dean of nursing Paul Smith stands outside Peterson Hall on the Linfield College nursing campus in Portland, Ore., Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2019. Linfield purchased a 10-building campus in Portland to host its nursing program.

Rob Manning / OPB

Linfield’s main campus is in McMinnville. The nursing school is on a tiny, full-to-capacity campus in Northwest Portland, right next to Legacy Good Samaritan Hospital.

Despite two parts of the college being 50 miles apart and having different academic focuses, administrators emphasize that they’re two parts of a whole. The lion’s share of students in Portland spend their first two years in the arts and sciences programs in McMinnville.

Linfield College in Portland, Ore., Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2019. Linfield purchased a 10-building campus in Portland for its nursing program in 2018.

Rob Manning / OPB

Julie Fitzwater, director of clinical education for undergraduate studies at Linfield, said those two years in McMinnville help her nursing students.

“They are building the groundwork, so they can think and talk and write and be open to different perspectives as a nursing student,” Fitzwater said.

The nursing school is expanding to a campus in East Portland, which administrators say will help them meet growing demand. Davis said Linfield is turning a corner. The college saw significantly more new students enrolling this fall than a year ago.

“The important story is that we’re up 40% this year,” Davis said, pointing to a spike in deposits from interested families over the summer.

Administration officials said there were also signs that Linfield’s incoming freshman class will be among the most diverse in the college’s history.

Faculty Express Fear And Frustration

As enrollment grows, some faculty wonder about the college’s cuts – particularly the voluntary separations and retirements. Despite assurances from administrators about the importance of liberal arts, professors in McMinnville are concerned about gaps in the art, German language and journalism programs.

Staff pressed faculty leaders over the summer in a memo to university leaders, from the executive council of the faculty assembly titled “Statement of Concerns and Thoughts on Moving Forward.”

The July memo said more than two-thirds of professors expressed a lack of confidence in the president, but when asked if the faculty should hold an “official vote of no confidence,” 83% of professors said no.

Faculty members said they didn’t want an official vote because it could grab national attention and undermine student recruitment efforts, and they weren’t convinced a “no confidence” vote would be received as anything more than a statement of general dissatisfaction with recent budget cuts.

Related: Saying Goodbye To The Oregon College Of Art And Craft

Numerous faculty members contacted by OPB didn’t respond, or would only discuss their concerns if their names weren’t used. The July memo from faculty points to a problematic culture on campus.

“In order to move forward on rebuilding our institution, the faculty feel that we must reflect critically on what occurred over the last year and that the President and Board of Trustees understands the precarious position we are in as an institution and the frustration and fear felt widely by our constituency,” the executive council wrote “on behalf of the faculty assembly.”

The memo said at one point Davis suggested faculty leaders help identify faculty positions to eliminate – a request faculty leaders said would violate college policy.

The memo goes on to list three major areas of concern with college leadership: shared governance; professional conduct and effectiveness of leadership; and academic freedom and tenure.

“We have been given reason to doubt [the current administration’s] commitment to shared governance, dedication to the liberal arts, genuine willingness to work with the faculty in pursuit of strategic institutional goals, dedication to collaboration, and commitment to protect academic freedom and tenure,” the memo said.

The Future: Linfield University

Davis wrote his own message to the Linfield community a few days after the faculty memo. Its title: “Linfield University: The Case for Change.”

Davis said he and the faculty are working toward the same goals: a strong college with nursing and liberal arts, and support for tenure. But he argues the college has to change as the world changes around it. In his July memo, Davis said part of the reason for Linfield’s restructuring was in response to a law the Oregon legislature passed last May allowing community colleges to confer bachelor’s degrees. He said it “will make recruiting to Linfield College even more difficult.”

Davis said it’s already hard to differentiate Linfield from community colleges.

Related: Oregon Colleges Forced To Adjust As Student Priorities Expand

To facilitate growth and preserve its liberal arts core, Linfield College is exploring ways to configure itself into different schools, as it becomes Linfield University,” Davis said.

Davis told OPB that he anticipates a graduate program in healthcare, but faculty members said they aren’t clear on what other academic areas will be prioritized as the school evolves.

The faculty’s July memo a few days earlier expressed as much, saying “the plan for restructuring the college has not been adequately explained, defended or placed within the larger context of a strategic plan for the institution.”

Davis said part of the solution is to continue to rein in costs, but he said it’s also critical to attracting more students, at a time when demographers predict a falling number of college-bound students. Davis suggests colleges can buck that trend by working harder to enroll students they might not have gone after in the past.

“There are less of the traditional, college-enrollment students – i.e. white, middle class – who are graduating, while there are significant increases in brown and black and other underrepresented minorities who are graduating,” Davis told OPB.

“So you have to engage those communities, to provide them an opportunity, and show them that you are welcoming.”

At the same time, Davis said Linfield has to be cautious about how it invests limited financial aid dollars on students. Davis said Linfield has had too high a “discount rate” – the amount that tuition and fees are reduced so that students will come to a college.

Administrators point to two new approaches: financial aid specifically geared toward students who would be the first in their families to go to college; and a tuition cap for the top 5% of students enrolling at Linfield.