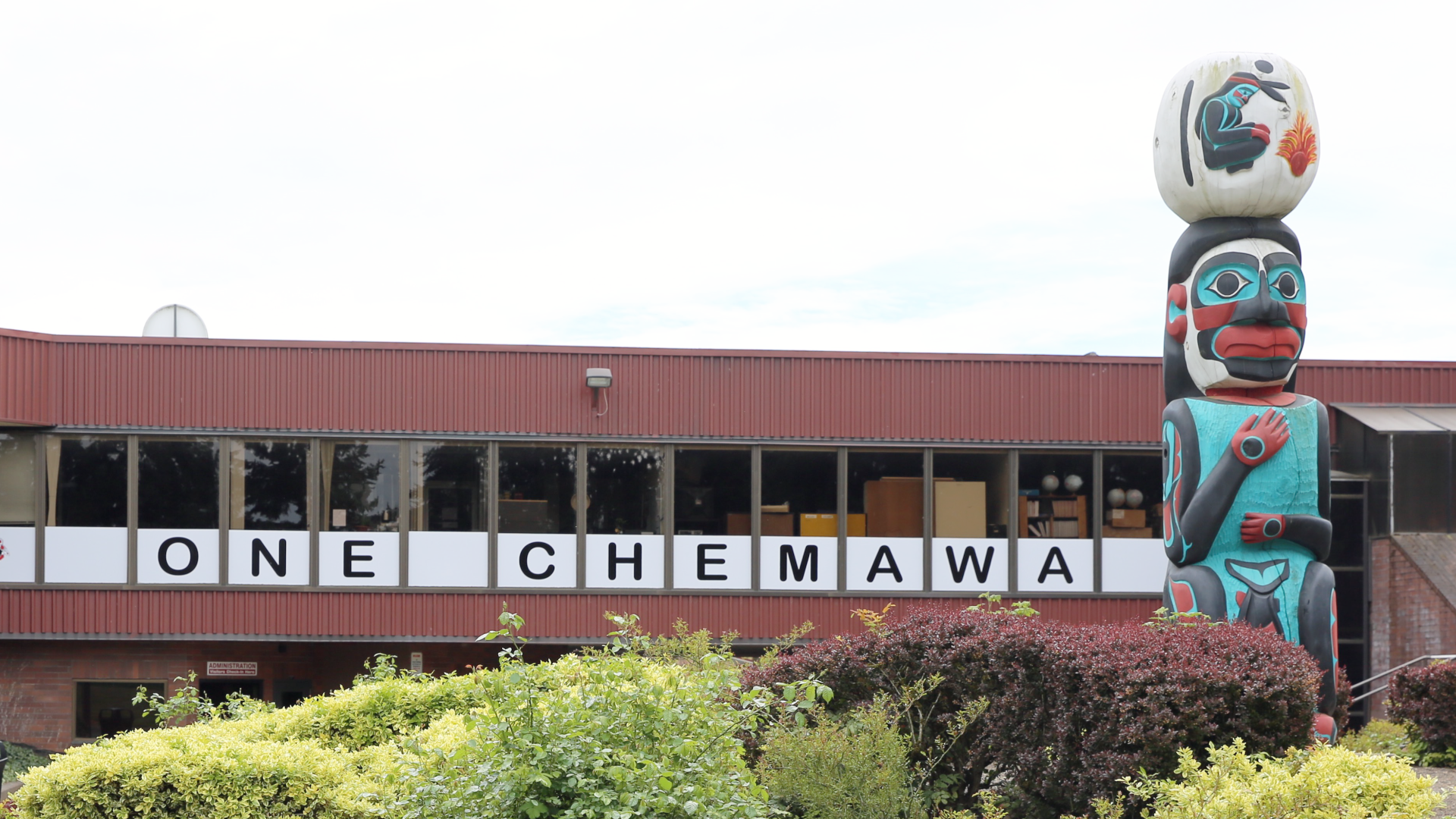

Chemawa Indian School is the oldest continuously running off-reservation Indian boarding school.

Rob Manning / OPB

A leading critic of how the federal government manages a Salem boarding school for Native American students wants changes at the top of the agency supervising the school. The Chemawa Indian School in Salem has faced mounting scrutiny from Oregon’s congressional delegation

Rep. Kurt Schrader, D-Oregon, wants Bureau of Indian Education Director Tony Dearman replaced after a tense and combative congressional hearing last month over the management and oversight of Chemawa Indian School, an off-reservation boarding school for Native American students, in Salem.

Schrader’s call for Dearman’s ouster was first reported in the newsletter Politico Pro and later confirmed to OPB.

In a statement to OPB, Schrader said that Chemawa students deserve an administration that prioritizes student safety and their educational and cultural needs. "Right now, I do not see that from BIE's leadership," Schrader said.

Schrader has grown increasingly frustrated with BIE over the last year and a half, as the congressman has pushed for answers about the school funded and managed by the federal government.

Members of Oregon's congressional delegation began asking questions about Chemawa in fall 2017, as OPB published a five-part series into various problems at the school, conveyed by former students, their parents and former staff. Among the most serious problems OPB found were the deaths of current or former students following questionable decisions by school administrators and lapses involving staff.

Chemawa was founded in the 1880s, amid a national push to forcibly assimilate Native Americans into Western society. The boarding school is considerably more humane now, but people who have worked there or sent children there confirm it lacks oversight and suffers from an insular, retaliatory culture. Many Chemawa students struggle with substance abuse, come from families in poverty or have suffered childhood trauma. Parents and former staff and students say the school often fails to properly support and educate the challenging students who enroll.

At a congressional hearing last month, former teacher Joy O’Renick repeated her account of a student named Flint Tall, who was expelled from Chemawa, in spite of his academic improvements. Tall’s mother, Rachel Bissonette, told OPB that her son was refused entry into local schools back home in South Dakota due to his expulsion from Chemawa. Without school to attend, Bissonette said her son resorted to drinking. Tall died in a drunk driving crash at age 15.

School administrators are reluctant to take responsibility for what happens to students after they leave Chemawa, regardless of the circumstances.

Another student, Melissa Abell, died of heart failure in a Chemawa dorm room in 2014. Police reports reviewed by OPB showed that students couldn’t immediately find staff to help and that the response was delayed because the incident was initially misidentified among staff as a fight, rather than an urgent medical situation.

Two other students died shortly after leaving Chemawa: Marshall Friday in 2017 and Robert Tillman in 2018. In both cases, the students appeared to be struggling with substance abuse and had been disciplined or expelled by the school shortly before they died.

Schrader has complained of a “gag order” preventing school staff from talking to his office. Department of Interior Deputy Assistant Secretary Mark Cruz told Schrader at a congressional hearing last month that he’d clarify that staff could talk to Congress. There’s no indication that such a message has been shared with staff, who have been on summer break since early May. Cruz’s credibility was called into question at last month’s hearing. He said that Chemawa administrators were unable to attend the hearing because they it was a “school day.” But the hearing took place almost two weeks after Chemawa had closed for graduation.