In 1971, a man and his son found the scattered remains of a young woman while they were camping in the woods just north of the Oregon-California border.

A pink and tan houndstooth coat was wrapped around the woman’s head. Nearby, investigators found 38 cents, a map of recreational sites in Northern California and a knife.

More than 44 years later, a small team of scientists and investigators are still trying to figure out who that young woman was.

"Somebody out there is missing her. Or was missing her," said Kari Lee, a Josephine County deputy and evidence technician.

Kari Lee looks at the National Missing and Unidentified Persons Data System website.

Jes Burns / OPB

If the woman were alive today, she would be between 58 and 69 years old.

"She’s poised to be identified," said Dr. Nici Vance, a forensic anthropologist with the Oregon State Medical Examiner’s Office. "But there’s a time continuum that we can’t stop."

The woman with the pink coat is one of more than 100 unidentified bodies in Oregon. The cases span decades. They include a woman who was found floating in the Willamette River in 1946, her hair in curlers and pins, and a man’s jawbone that was pulled up in a fisherman’s crab pot in April of this year near the mouth of the Columbia River.

It can take years of detective work to figure out who these people were in life and whether their families had reported them missing.

New tools — like DNA testing and a publicly searchable national case database for unidentified people, called NamUs — have made it easier to connect people who are reported missing with the unidentified bodies that end up in morgues and medical examiners offices. But law enforcement agencies don't always use the database.

Without an advocate, it’s easy for the body of a Jane or John Doe to be forgotten. But Lee is trying to make sure the woman in the pink coat won't be one of those bodies.

Lee works for the most notoriously underfunded sheriff's department in Oregon. Her official job includes going with deputies to crime scenes and ensuring that the evidence, including guns, drugs, backpacks and the odd moose head, is dated and properly stored.

But Lee's passion is to identify the woman discovered in the woods in 1971, who she calls Annie Doe. She discovered Annie Doe shortly after she started with the sheriff's office in 1998.

"I had just taken over the department, and I was organizing the homicide room. I came across this box, marked '71,'" she remembered.

Inside the cardboard box, Lee found a complete skeleton. A smaller cardboard box contained a skull. The pink and tan coat with large pink buttons was also in the box.

Lee said immediately, the situation felt wrong, "I know this wasn’t the place for her. She had a home, she had a family, she had friends. I wanted to find her home."

A ring found with the body had the initials AL scratched into the face.

NamUs / NamUs

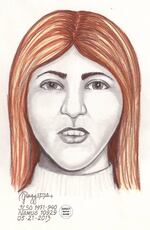

She’s hung artists sketches of the unidentified woman she calls Annie Doe and newspaper clippings related to the cold case on the wall above her desk, as a visual reminder to keep working on it.

"I’ve done a lot of digging. I look at it, and I think, 'What else can I do?'" said Lee.

The sheriff’s office never determined whether the woman was murdered; her body was badly damaged by the time it was discovered. An autopsy performed on the skeleton years later also failed to identify a cause of death.

Over the years, Lee has enlisted the help of a jewelry expert in Australia to learn more about a pair of distinctive silver rings found with the body. She's also sought out the 1971 guestbook of the Oregon Caves National Monument, just down the road from where the body was found.

“She’s definitely brought it to a level that it would have never gotten to, unless she was involved in it,” said Vance.

Unidentified bodies are officially the responsibility of the Oregon State Medical Examiner, but for years, the agency operated out of an office in North Portland with a tiny morgue.

"The freezer could hold five bodies, and that’s it," said Vance.

As a result, the bodies and skeletons remained boxed up in county sheriffs' evidence rooms and police departments across the state.

In 2003, after the medical examiner moved into a larger office, Vance began the process of collecting the unidentified bodies from law enforcement, re-examining them, and entering their profiles into NamUs.

Vance is now responsible for 128 bodies.

"Most of the people in Oregon have everything in place. They have DNA profiles, they have dental coding, they have x-rays," she said.

She entered Annie Doe into the unidentified persons database in 2013.

An artist's sketch of Annie Doe.

NamUs / NamUs

The entry includes a trove of details that could help a detective or family member identify her from across the country. She had long auburn hair streaked with blond. She was between 14 and 25 years old when she died. There are also photos of her clothes, her shoes and the unique silver rings that were found near her body. One has the letters "AL" scratched into the face.

" She’s so terribly identifiable," said Vance. "Now we need someone who is missing a loved one to come forward and say, 'I think that might be my sister.'"

So far, the challenges in Annie Doe’s case have outweighed the clues. Lee and Vance don’t know if the woman was ever reported missing in the 1970s. If she was, that missing person report could have been filed at any one of thousands of law enforcement agencies across the country.

"It was a very transient society in that period of time. She could be from anywhere. Absolutely anywhere," said Lee.

If a missing persons report was filed, it may have been lost. Further complicating the search, Vance said detectives across the country also often don’t enter missing persons reports into the NamUs database.

Instead, many detectives still rely on an older crime reporting system that's more difficult to search, called the National Crime Information Center, or NCIC.

"The NCIC system is what I would call an antiquated system," said Vance. "It was never created for missing people, it was created for missing objects. Stolen vehicles, boats that got untied from their moorings. It was a way for law enforcement to enter serial numbers and descriptions."

Vance said it’s much harder to use that database to search for a person using an identifying characteristic like an eagle tattoo or an appendectomy scar. And finally, while NamUs is a public database that families of the missing can easily search themselves, many people have never heard of it.

"One of the startling things I’ve learned over the years is that sometimes families simply do not know about this," she said. "The resources are still fragmented, especially on the missing person side."

Kari Lee has decorated the wall above her desk with images and clippings related to the unidentified woman.

Jes Burns / OPB

Since Annie Doe was entered into NamUs, she’s come up as a possible match for five missing women. Lee said one of the candidates even appeared to be wearing the same houndstooth coat in her missing person photo. But one by one, the women were ruled out as matches using dental records and DNA.

"That was a crushing blow. I was very hopeful we had finally found Annie’s home," said Lee.

Vance is convinced that eventually, somebody will recognize the woman’s profile in the database.

"Her friends and perhaps her siblings are still out there. Someone knew this girl, absolutely. We just need to find out whom," she said.

For now, the skeleton waits at the State Medical Examiner's office.

Vance carefully laid out the bones, wrapped them in protective exam paper, and placed them in a ventilated plastic container. She knows that for every person she is able to identify, there are many more she cannot. Her locked storage room will be a final resting place for some people.

"It's sad, certainly, in a way," she said. "I'm at peace with that, because I know they are safe, and we will never give up."

The Center of Investigative Reporting's new radio show Reveal designed a tool to make it easier for the public to search.

This story is part of a larger project by Reveal, public radio’s first investigative news show. You can listen to "Left For Dead" from Reveal, CIR and PRX on OPB Tuesday at 9 p.m.