Historically, media organizations have shied away from reporting on suicide out of fear that coverage will lead to a contagion effect.

But this week, media organizations across the state are working together to talk about this public health crisis that kills more than 800 Oregonians a year.

That’s because the research now shows us that the old approach — studiously avoiding coverage — isn’t working.

“There’s a growing body of evidence that reporting responsibly on suicide can actually make communities safer,” Dwight Holton, executive director of the nonprofit Lines for Life, told OPB’s "Morning Edition." “The new evidence shows that if we talk about suicide responsibly, if we talk about suicide in a context of connecting people to resources and in telling stories of hope and healing, that we can actually make communities safer.”

Oregon has one of the nation’s highest suicide rates. No one is quite sure why.

“It’s complex,” Holton said. “Our challenge is to figure out how we answer it, whatever the cause. We see a growing crisis, a twin crisis really, of suicide and addiction. The answer to that twin crisis is hope. That’s part of what’s really important about this week.”

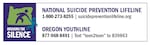

What Holton and other mental health advocates hope to see is responsible news coverage that points people toward resources, and reasons for optimism.

“Whenever I talk about the suicide rate in Oregon, I’m also quick to point out that for every one person who dies by suicide, there are 280 people who think seriously about it, but don’t,” he said. “Those are 280 stories of hope and healing and success — people who go on to live their lives.”

He says responsible coverage means careful language and plenty of context.

“There are words we use that stigmatize getting help. For example, we talk about ‘committing suicide.’ When we think about ‘committing,’ we think about committing a crime,” he said. “So people in this community talk about ‘death by suicide.’ We’re trying not to stigmatize getting help.

"The most important thing we can do is begin a conversation to bring this public health crisis out of the shadows: we normalize having a bad period, and we normalize getting help around it.”

Holton, a former federal prosecutor, hopes increased conversation will lead to increased attention from lawmakers to building better mental health and suicide prevention networks locally and across the state.

Listen to the entire conversation using the audio player at the top of this story.