Courtesy Anis Mojgani, Image by Ryan Longnecker

Poetry gets a bad rap sometimes. When another artist, say a ceramicist or a musician, bemoans how little they make, it’s a bit of a joke to follow with something like: “It could be worse, at least I’m not a poet.”

Don’t say that to Anis Mojgani.

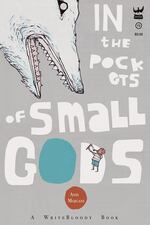

It took us weeks to get him into the studio to talk about his new book, “In the Pockets of Small Gods,” because he’s so busy flying around the country to perform everywhere from colleges to TEDx events and HBO. He's a two-time National Poetry Slam champion and one-time World Cup winner and regularly emcees events and slams, such as Verselandia, the annual high school poetry slam organized by Literary Arts. Somehow he still manages to find time to do the art on the covers and between the pages of his poetry collections (he studied comic book illustration at the Savannah College of Art and Design before pursuing poetry).

“It’s wild to me that there’s a world that we live in that does allow — not on a large scale — but it does allow individuals to go out and make a living as a poet,” Mojgani said. “There’s other things I’d like to be exploring, but there’s this weird job security in what I do. I know how to make this work as a job.”

Anis Mojgani does the cover art of all his books, as well as the illustrations on his graphic novella, "The Pocket Knife Bible."

Courtesy of WriteBloody Book

Mojgani’s work is known for its optimism and joy, but his newest book is all about plumbing the emotional depths of grief. The poems of “In the Pockets of Small Gods” follow Mojgani’s journey after the dissolution of his marriage, which ended in 2015 after several years of strife, and the older sorrow it dredged up.

“During that period of time, one of the things I very much learned about grief is it sort of has the tendency to throw you back through other chapters of grief that you may or may not have actually fully dealt with,” Mojgani said. “My best friend, Jeff, committed suicide in 2006, 2007, and that was something I thought I had dealt with, but I don’t think I ever really had.”

One reason it was so hard to process, Mojgani explains in his poems, is that Jeff’s disappearance was cloaked in mystery. He left a note saying he was going away and don’t try to find him. And while Mojgani suspected suicide, no one could be sure.

“I had to carry this idea that I probably won’t see this person again,” he said. “I don’t want to hope that he’s still alive, but I couldn’t help but — and I speak to it in one of the other poems — about how that, just having these visions and dreams and hopes that maybe one day, there’d just be a knock on my door, and here’d be this disheveled, wild, bearded man with these eyes that I knew.”

Several years later, Mojgani got a call that they had found some of Jeff’s remains in a lake near where they lived. But knowing he was gone didn’t bring any closure, as Mojgani explores in the poem “Some Sort of Funeral”:

I remember all this unnamed and nameless this that was in me

All this curdling blood and anger and want

And if I could tell my then self something now I would tell him

that the wolves in the woods sometimes make halos to better hold us and

sometimes the wolf makes the halos that we might be better held

I would say Anis––it is very possible for a person to be loved and yet still feel so alone that they just have to leave

O Jeff

what rattled inside the flower your chest held

so tightly

that you had to go live once again back with the animals

o closeness that was you

Interlaced with the stories of Jeff and Mojgani’s former partner are a small number of literary figures like Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath, and a veritable pantheon of figures from Greek mythology (the book is, after all, titled “In the Pocket of Small Gods”).

“Those are stories that I’ve always carried around with me, that I’ve always found fascinating,” Mojgani said. “My brain is one that likes to find connections, and see where things seem similar and echo one another, and using different tales to help with that.”

And so Mojgani puts himself in the place of Leda, being visited by swans (or a is it a lustful Zeus?); or in the place of Orpheus, failing to bring his love back from Hades; or “In the Canoe with Hermes”:

I am no king of clouds. Have never had this need to clutch so tightly these bolts of thunder. No need to sit upon these patterns of weather, looking down upon the earth below my feet, searching for something soft to throw against something hard. More so quick-footed and ankle-winged. Sleeping under sheepskin. Carving turtles into lyres. And holding the hands of those traveling to the next world. We are all traveling to the next world. I can only give my self to another self and be fine with this. I do not know if I know how to do that anymore. Being fine with this.

How does one work with sorrow while not eventually working for it?

Does Hermes work with death or for death?

All the people I see are deers. I keep my distance.

Wait for them to pass, or to become people again.

Ultimately, Mojgani does find peace, or some semblance of it, in “Perseus’ Spoon”:

As I have learned more

how to hold my heart again

and whisper into it

and once more listen

a little better

to the songs it sings

even mouthless with

no mouth it sings

and even when no note

heard nor even made

I am listening or at least learning

to always try to

so perhaps it is not

the longest night we at times find ourselves in

but simply the slowest dew

forming upon us

Mojgani will perform with a slew of poets and musicians on April 28 at Bunk Bar, and then he'll read with two of his poetry besties — Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz and Derrick Brown — on April 29 at Powell's City of Books and on May 3 at Literary Arts. More info is on his site.

Also, if you want to hear Mojgani talk more about the history of slam poetry, as well as hear performances by the best young slam poets Portland has to offer, check out the recent Verselandia episode from the Literary Arts "Archive Project."