Note: This story involves details of sexual abuse. If you or someone you know may be a victim of sexual abuse, confidential support, information and advice are available at the National Sexual Assault Hotline by calling 800-656-4673. Text chat is also available online.

FILE-A sign seen at an open forum at the St. Helens Senior Center on Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, where community members discussed holding school district leaders accountable and keeping children safe.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

St. Helens School District officials are being investigated and scrutinized by Oregon’s Department of Human Services, put on leave, criminally charged, reprimanded by the governor, and eviscerated in the court of public opinion for failing to alert authorities about numerous allegations of sexual abuse spanning years.

Now, it’s time to reckon with a deeply upsetting truth: The problems in St. Helens illustrate a much broader pattern of predatory educators grooming, harassing and sexually abusing students across Oregon and the country.

An estimated 10% of students nationwide — one in 10 young people — will experience educator sexual misconduct by the time they graduate.

That figure comes from a landmark research analysis from the early 2000s by researcher and professor Charol Shakeshaft, which was reviewed and updated two years ago by the U.S. Department of Education‘s Office for Civil Rights. In 2022, a multistate survey with thousands of participants showed rates may be closer to 12%, with the majority of participants facing sexual comments from their teachers.

Related: 10 St. Helens employees now on leave in sexual abuse case. School district offers few details

Sexual misconduct against students can include inappropriate verbal, visual and physical behaviors, ranging from crude comments and nude photographs to sexual assault and rape. It can be perpetrated by any school employee.

Rates differ based on student age and even parts of the country. But based on national averages, tens of thousands of Oregon children — the equivalent of two students in every classroom — are likely to endure educator sexual misconduct during their school career.

Cases of sexual abuse have alarmed Oregon school communities for years, including patterns of abuse at public and private schools in Portland, and more recently in Salem-Keizer. Still, national experts say this is an understudied and underreported area.

When the news outlet Business Insider investigated sexual abuse across hundreds of American school districts, they described it as an “epidemic,” one filled with “shoddy investigations, quiet resignations, and a culture of secrecy” that have “protected predators, not students.”

Oregon Public Broadcasting analyzed records obtained by Business Insider from the 10 largest public school districts in both Oregon and Washington to better understand how this issue is playing out in the Pacific Northwest. The records detail allegations and disciplinary actions from educator misconduct cases between Jan. 1, 2017, and Dec. 31, 2022.

Roughly 200 records were collected from the states’ largest districts.

These records document disturbing patterns of grooming, harassment and abuse at schools across the region. Taken as a whole, the districts’ responses paint a troubling picture, one in which their willingness to share information publicly is often inconsistent and incomplete.

Some school districts refused to provide records in a timely manner, claimed to have no reports, or refused to fill the request without heavy redactions or exorbitant fees. As a result, some districts may be disproportionately represented in the records.

The details vary. Some resignation agreements or settlements give few specifics on the cause of the individual’s departure. Some records maintain the educator’s innocence. Many outline the paid administrative leave employees were placed on, the warnings and policy reminders they were given about boundaries, or the extended “sick leave” they eventually took.

Some provide graphic details reported by students, other educators or family members.

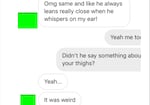

“He’s such a perv,” one screenshot reads, “and he touches [redacted]’s leg and says she is attractive and pretty and he called this girl’s moms phone and said ‘I know your listening cowgirl see you on Monday.’ ”

The message continues, “he needs to understand these are little girls he is talking to.”

A text exchange between two students in Washington from 2019 shares some of their concerns regarding a middle school teacher who later had his teaching license revoked and was convicted of molesting his stepdaughter. The text message was part of the public records obtained by Business Insider and shared with OPB.

Obtained via Business Insider

The allegations are far-ranging. Whispering in young girls’ ears. Touching their hair. Watching porn in the classroom. Sending photos of their penises. Convincing teen boys and girls to come to their homes and have sex with them or others.

One graphic example from the 2015-16 school year at a Washington middle school details a teacher in his then-late 50s who talked with a female student every day before or after class, often both. Eventually, she would go to his classroom before school started, and he called her over to sit on his lap. This, as she later reported to police, led to him touching her breasts and butt, touching her over her clothing, then up her shirt or down her pants. They soon started “kissing and making out,” according to the report.

“She did not know how long that went on for, but they started performing oral sex on each other,” the report states. “All of this occurred in his classroom.”

Research indicates sexual misconduct of students is most commonly committed by classroom teachers, coaches or physical education teachers. The vast majority of perpetrators — nearly 90%, according to one survey — are male. The targeted students are most commonly high school girls.

While most educators in public and private schools do not harm students, those who do may be harming many children. A 2010 Government Accountability Office study found that offenders can have “dozens, hundreds, and even thousands of victims, sometimes without ever being caught.”

Handwritten notes show concerns about a physical education teacher in Washington touching students. The scan was part of public records obtained by Business Insider and shared with OPB.

Obtained via Business Insider

What happens to accused educators varies a lot. Some escape serious consequences and move on to permanent or substitute teaching jobs in other areas. Some are prosecuted.

There were cases in the Business Insider records where several, if not dozens of students reported the same educator, created social media accounts to showcase the teacher’s behavior, or protested they be removed. Sometimes, students spoke up, but the evidence was deemed insufficient for concern, and nothing was done.

In the 2015-16 Washington example, that teacher was convicted years later of child molestation, sentenced to house arrest and prison time, and became a registered sex offender.

These incidents — including the multiple allegations of abuse that went unreported in St. Helens and have been met with public uproar — show how trust is eroded across school communities.

The country’s education system depends on families feeling safe sending their children to school, and most educators are extremely dedicated to protecting and caring for students.

But what happens if schools don’t do enough, and what can be done to avoid the harm in the first place?

‘Nobody talked about it, but everyone knew’

Lindsey Troutman said complaints from the middle schoolers she worked with started small.

Troutman was a Youth Essentials Coordinator in the Centennial School District through the nonprofit REAP, Inc. She was not employed in one of the 10 largest districts in Oregon, so this case was not one of the records sought by Business Insider.

As soon as Troutman began working at Centennial in the fall of 2023, she said a few students would casually, offhandedly, say things about one teacher in particular — comments like, “I don’t like this teacher,” or “This teacher is weird.”

“I didn’t think too much of it at the time,” she told OPB, “because I know students don’t like teachers for many reasons.”

That’s often the case — details that later show a clear pattern may not seem significant at the time.

As more students made comments, though, Troutman decided to ask a few of the students she worked with regularly if everything was okay. The concerns were still smaller, more elusive things, like “I don’t like the way that this teacher looks at me.”

But then she learned complaints were filed with the school about the same teacher the year before and that little action had reportedly been taken.

Multiple students told Troutman they would wear baggier clothes when they were in the teacher’s class because they felt like he would look at them too long — one said he looked at her too long when she wore a shorter shirt than usual; another student told her he watched her change into a jacket.

More detailed concerns came out over time from more students. The teacher would tell girls he doesn’t like when they get boyfriends because then they “leave him,” Troutman said, and he was active with the students on social media, especially TikTok and Snapchat.

“I remember a student told me that one time she was in a grocery store, and [he] called her on Snapchat,” Troutman recalled. “She answered, and he told her, ‘Pretend that you’re talking to one of your friends.’ ”

The teacher in question has no criminal charges in Oregon, according to court records, nor does he have any sanctions on his teaching license. For those reasons, OPB is not naming him. According to the Teacher Standards and Practices Commission database, he has a preliminary license effective until August 2027.

Former REAP nonprofit worker Lindsey Troutman sits with her collected notes detailing the timeline of concerns expressed to her by a handful of middle school students in the Centennial School District during the 2023-24 school year. Troutman reported the incidents and argues leaders failed to follow mandatory reporting and Title IX requirements.

Natalie Pate / OPB

Troutman spoke with her supervisor at REAP about the students’ concerns and reported them to the principal. But the meetings didn’t result in any obvious sanctions toward the teacher, and she said it wasn’t always clear why decisions were made the way they were regarding the students.

The first two students who opened up to Troutman asked to be removed from his class, but only one was initially. When the second was promised a different seat in the classroom, Troutman said, the teacher didn’t move them very far. They were later transferred out because the teacher was “inappropriately mean [and] rude to this student,” she recalled.

“Students expressed their concern; they expressed being uncomfortable. They were forced to stay in that class,” she said. “[He] knew that these students had reported him, and … [another] staff member just explicitly said that she thought they were lying.”

Kassie Swenson, a communications consultant working with the Centennial School District, responded to OPB on behalf of the district. She said the district couldn’t comment on specific investigations.

“School and district staff address all allegations with care and concern for students as the highest priority,” she said.

Swenson said all Centennial staff are required to complete mandatory reporter training annually to recognize and respond to signs of abuse, neglect and sexual conduct and to report these concerns.

“We do not tolerate any behaviors that place our students’ well-being at risk, and we take seriously any allegations of threats to student safety,” she said. “Sexual conduct involving students by district employees, contractors, agents and volunteers is not tolerated.”

Even though more students spoke up throughout the year, Troutman felt like the school and work environment got worse after the reports were made.

She said some of the students explicitly said things like, “[I] shouldn’t have said anything. Now, everything’s so much worse.” Some felt guilty, saying, “What if I ruined his life?” or “I should have been smarter. I should have known better.”

No matter who Troutman complained to or met with, she said the students’ concerns weren’t addressed.

“— Lindsey Troutman, former Youth Essentials Coordinator in the Centennial School DistrictBasically, every single day for five months, I felt like I was going crazy because no one seemed to be taking it as seriously as I felt like it needed to be.”

“Basically, every single day for five months, I felt like I was going crazy because no one seemed to be taking it as seriously as I felt like it needed to be,” she said. “It was like, ‘I must be missing something. Everyone else must know something I don’t, or else this would be handled completely differently.’ ”

Swenson explained that under Centennial’s policy, when the district receives a report of sexual conduct by a staff member, the district reports the information to the Oregon Department of Education or the Teacher Standards and Practices Commission, as appropriate.

The staff member is immediately placed on administrative leave, she said, and the district takes necessary actions to ensure the student’s safety. A mandatory report is made to the Department of Human Services and/or law enforcement, and the district communicates with the families of the students.

It’s not clear if those steps were taken in this case. Troutman was told it was an HR issue. When she later called the parents of several students who reported allegations to her, she said they told her they had not been contacted as part of any investigation by the district.

To protect student privacy and comply with legal requirements, the district can’t give out specific information about individual cases. As a result, Swenson stressed, those filing a complaint may not be fully aware of the district’s response or the actions taken following their report.

Swenson said the district will notify the victim of the alleged misconduct about any actions taken as a result of the report. They can share some information, like what safeguards will go into place to protect the student. But other details, like staff discipline, can’t be disclosed.

REAP officials also told OPB that they are careful to comply with all laws and regulations for reporting inappropriate conduct. They said they encourage employees to share concerns while acknowledging that the organization is limited by “privacy and confidentiality obligations.”

Troutman said she and at least two other REAP employees provided documentation of the students’ concerns — including statements and emails — to top district administrators.

In the spring, Troutman attended a meeting with her boss, the executive director of REAP and the school principal, but she was reportedly not given a chance to speak about the violations and her concerns. That was after months of trying to get an investigation and action taken for the students. She quit out of frustration.

“No one believes kids,” Troutman said. “No one believes teen girls. No one believes girls in general.”

Swenson confirmed the teacher in question no longer works in the district but could not provide any more details. Troutman has heard about more inappropriate behavior allegations against another teacher who’s still listed on the middle school’s staff directory.

To Troutman’s knowledge, no report was made by school officials to the police or to Oregon DHS regarding either educator. When OPB asked about the two teachers, DHS officials said, “We have nothing we can share on those individuals.”

Former REAP nonprofit worker Lindsey Troutman's collected notes detail the timeline of concerns expressed to her by a handful of middle school students in the Centennial School District during the 2023-24 school year. Troutman reported the incidents and argues leaders failed to follow mandatory reporting and Title IX requirements.

Natalie Pate / OPB

Troutman was only able to see so many pieces of the puzzle. But to her, the situation felt like one more example of authorities doubting teens. She said she doesn’t blame students who are too scared to report their concerns.

Students who reported educator misconduct in the national 2022 survey were significantly more likely to deal with long-term effects, including suicide attempts and alcohol and drug use. Experts aren’t positive if the long-term consequences are a direct result of the abuse itself, if reporting the abuse may be a compounding factor, or if the students who were targeted are at greater risk of ongoing trauma. Researchers say abusers often target students they perceive to be more vulnerable, believing it will reduce the chance they’ll get caught.

A 2012 report from the National Sexual Violence Resource Center says just over a third — an estimated 37% — of all sexual assaults are reported to the police. Data from the 2022 survey shows the rate of disclosure to authorities about educator sexual misconduct specifically is even lower — only 4%.

False reporting is extremely rare, between 2-10% for all sexual assault allegations, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center. False reporting refers to cases where the accusations are proven incorrect through an investigation. Even though it’s unlikely someone is lying when they report, survivors are often met with doubt, criticism, blame, apathy or retaliation.

Troutman struggled as a bystander and as one of the grownups. She described it as the worst several months of her life, despite the love and respect she felt toward her employer, REAP. She could only imagine what that must have felt like to the middle schoolers.

“I would come home from work sobbing about it. I would call my mom sobbing about it. I would call my boss sobbing about it. And it just felt insane to me,” she said. “Like, I’m an adult. I’m an employee. I went to college and have that education behind me, and still, I was just like, ‘I don’t know what the hell I can even do here.’

“It just was the strangest situation I’ve ever been in where nobody talked about it, but everyone knew about it,” she added. “It was really, really, really awful.”

Troutman has lingering concerns about the teacher working elsewhere and the well-being of the students. She wants families to be more aware of their rights under Title IX laws, which apply to both K-12 and college students.

And for her former students: “I hope that they reach a point where they know that it wasn’t their fault, that it wasn’t a failing on their behalf,” she said. “I hope that they find that power within themselves to understand that and to believe that.”

Preventing student sex abuse at every level

Seeing an individual case in your community or the news may be alarming but easy to dismiss as the actions of a singular bad actor.

In St. Helens, a series of events in short succession pushed parent and student outrage to a boiling point. Community pressure over a $3.5 million settlement to a survivor and the arrest of three educators forced out top school officials and have led to an ongoing reckoning in the small city.

And the solution may seem simple — report any concerns you see, and they’ll be handled. But while reporting to state or local authorities is critical, it’s often more complicated than some realize.

All school employees are mandatory reporters, meaning if they learn of suspected abuse, they should immediately call the state’s child abuse hotline or law enforcement. At that point, it’s the responsibility of law enforcement to investigate any criminal elements, and DHS to investigate any abuse.

Districts have to strike a delicate balance. On the one hand, they must support survivors and investigate concerns fully. On the other, they have to proceed under the assumption of “innocent until proven guilty” and follow legal and contractual rules protecting an accused employee.

A social media post lists allegations against a middle school teacher in Oregon. According to the district, this case was unsubstantiated. The screenshot was in a document from 2021, which was included in public records obtained by Business Insider and shared with OPB.

Obtained via Business Insider

It can also be difficult to discern what rises to the level of alarm. But experts say the seemingly grey-area comments or actions can be warning signs everyone should pay attention to.

Advocates want to see more action at every level. Among other ideas, lawmakers and school officials can:

- Increase the number of qualified staff in school buildings;

- Train educators, families and students on sexual violence prevention;

- Adopt zero-tolerance policies in schools for boundary violations of a sexual nature;

- Consider harsher criminalization of these abuses when committed by educators specifically;

- And ensure students who allege educator sexual misconduct are provided with support and counseling.

Northwest lawmakers have been trying to tackle this issue in many ways over the years.

In 2009, for example, Oregon legislators unanimously passed House Bill 2062.

This law does several things. It increases teacher background checks when applying to new schools, prevents districts from suppressing crucial information about an employee’s sexual misconduct or abuse, and allows families to bring action against the education provider if the school employee previously committed abuse and the provider didn’t investigate or report the abuse.

Oregon and Washington are two of only 17 states in the country that have key protections in place to avoid what’s known as “passing the trash” — sending an educator who has abused students to just go work in another school or district.

These states require that prospective schools check a candidate’s disciplinary history and that previous schools disclose teacher sexual misconduct. Several states only require one of those — or neither.

Oregon and Washington are also among only a select few states that prohibit any collective bargaining agreement, contract or other agreement from allowing an employee to resign or retire in exchange for cleansing their personnel file of references to misconduct.

But even with many of the right policies in place across the Pacific Northwest, cases like St. Helens show our laws are only as good as the people who follow and enforce them. And the stakes are high.

As Gov. Tina Kotek’s office put it: “Even one student experiencing harm at the hands of an educator is unacceptable.”

If you or someone you know may be a victim of sexual abuse, confidential support, information and advice are available at the National Sexual Assault Hotline by calling 800-656-4673.