Last month, Oregon reported its first human case of H5N1 bird flu, in a poultry farm worker who caught the virus from a sick bird. It is one of 58 confirmed human cases in the U.S. so far.

Experts and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention agree that current risk to the general public is low, primarily because there are no examples of the virus spreading from one human to another. The cases so far have been rare animal-to-human spillover events.

But flu viruses evolve, and it won’t take too many leaps for the bird flu to gain the ability to spread among people. The CDC rates the virus’s potential for “emergence,” evolving to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission, as moderate.

FILE - In this photo provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, an animal caretaker collects a blood sample from a dairy calf vaccinated against bird flu in a containment building at the National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Wednesday, July 31, 2024.

U.S. Department of Agriculture / AP

If those last two sentences are triggering traumatic COVID-19 memories, know this: even if bird flu makes the leap to humans, it wouldn’t necessarily look like the COVID-19 pandemic all over again.

Historically, flu viruses have been less contagious than the coronavirus, with each case infecting between one or two other susceptible people on average. Compare that to the two to three others on average the ancestral coronavirus variant, or eight others on average for the omicron variant.

And because we have a long running experience with flu pandemics, the United States has a stockpile of candidate vaccines for bird flu, and a stockpile of the currently recommended antiviral treatment, oseltamivir, also known by the brand name Tamiflu.

“Influenza is a place where the United States is very well prepared,” said Melissa Sutton, the medical director for respiratory viral pathogens at the Oregon Health Authority.

So read on, for a deep dive into what we know about the virus now, and what to expect from it in the future.

1. Avian flu is, at present, bad at infecting humans

The bird flu virus has evolved to thrive and replicate in the guts and lungs of ducks and other birds. This is its speciality. It has decimated the pelican population in Peru, wiped out Eurasian Wigeons in the Netherlands, and killed hundreds of millions of chickens across the globe.

Its potent power to infect birds is also why it’s bad at infecting people.

In order to infect a host, a virus needs to do two things: first, bind to the host animal’s cells, and second, recruit help from a host enzyme that cuts the virus up and lets it slip inside the cell to replicate.

The part of the virus that binds to the host animal’s cell is called the hemagglutinin.

The hemagglutinin in the bird flu is adapted to the cells found in the lungs and guts of birds. Fortunately, humans share relatively few of those same target cells.

“Humans have a little bit of the receptor material for Avian H5N1, “but not enough to really support replication of the virus,” said Bill Messer, a biologist at OHSU who specializes in the ecology and evolution of viruses.

Biologists call this a host restriction factor. This is also likely why it can’t transmit between people: it can’t replicate very well in us.

The first known case of H5N1 avian flu in a person was in 1997, in Hong Kong. Since then, in 27 years, there have been less than 1,000 confirmed human cases globally.

There are limits, though, to the virus’s host restriction. This year in the United States, avian flu has made the leap to infecting a number of mammal species, notably dairy cows and cats.

In those cows, it appears to be replicating particularly in their mammary glands. That’s leading to high levels of the virus detected in unpasteurized milk. In cats, the virus has been fatal; it appears to particularly affect the cells in their central nervous system.

Messer says one interesting aspect of the virus’s structure is that it can pair well with lots of different host enzymes, which helps it slip inside the cells it binds to.

“That does smack of an evolutionary adaptation,” he said, “to be able to infect other vertebrate hosts.”

This undated electron microscopic image provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows two Influenza A (H5N1) virions, a type of bird flu virus. (Cynthia Goldsmith, Jackie Katz/CDC via AP)

Cynthia Goldsmith, Jackie Katz / AP

2. There are two paths the virus could take to get better at infecting humans

Good news is, you’re not a duck or a cat. The bad news is, viruses evolve.

Viruses accumulate mutations - little mistakes - when they copy themselves. Over time, those mistakes can add up to something that helps a virus gain entry into a new host’s cells.

According to Messer, historically, it’s taken between three and five mutations of a flu virus’s hemagglutinin to allow it to shift from one animal host (birds, cows) to another (humans).

“We know from COVID-19, that’s not a huge number of mutations,” Messer said.

And there’s a second path, a shortcut that bird flu could take to gain the ability to get into people and transmit between us.

It’s called reassortment. When two different viruses infect the same host cell, they can swap entire strands of their genome.

Swapping a gene segment with the seasonal flu is one way avian flu could get better at infecting people. That could happen if a person is infected with both H5 bird flu and the seasonal flu simultaneously.

“We recommend seasonal influenza vaccine every year for every person for all the reasons, but an important reason is that we wouldn’t want someone to have both infections,” said OHA’s Sutton.

To be clear: the flu shot doesn’t protect against avian flu. But fewer seasonal flu infections means fewer chances for the virus to evolve and become transmissible.

3. H5N1 isn’t making people in the U.S. very sick so far. If the virus evolves, that could change

Historically, the avian flu has had a high mortality rate. Between 1997 and 2021, there were 833 cases reported in about 20 countries. In about half of those cases, the people infected with avian flu died.

While that is a high case fatality rate, public health experts suspected it was artificially inflated, because most countries were only catching cases when people were seriously ill or hospitalized, while milder cases went undetected.

In the U.S., all 58 confirmed human cases were mild, and people have fully recovered. Only one person with the virus was hospitalized, and it’s not clear that avian flu was the reason. “What we’re seeing is quite reassuring,” Sutton said.

Messer agrees that the current evidence suggests the virus is not particularly virulent, and it’s possible it will remain that way, even if it gains the ability to enter human cells.

Other recent influenza pandemics, like the 2009 swine flu pandemic, were comparatively mild.

But Messer says the question of how sick the virus could make us if it evolves is a profound unknown.

The virus may only be mild because it has to struggle to enter every human airway cell it infects. If it evolves to get better at binding to human lung cells, that could be enough to make it a more virulent infection.

Messer said that just because the virus is mild in humans right now, that “does not in any way ensure that it will remain mild.”

Chickens stand in their cages at a farm, in Iowa, Nov. 16, 2009. Four more people, all Colorado poultry workers, have been diagnosed with bird flu infections, health officials said late Sunday, June 14, 2024. The new cases are the sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth in the United States diagnosed with the bird flu, which so far has caused mild illness in humans.

Charlie Neibergall / AP

4. The U.S. is doing less surveillance for bird flu than it should, but more than you might think

Virtually all known cases of H5 bird flu in the U.S. - 56 out of 58 - have been found in people who had contact with infected dairy cattle or poultry.

Humans are getting bird flu, Sutton said, from touching their eyes, nose, or mouth after direct contact with an infected animal or its droppings, or from inhaling contaminated droppings or dust.

Given the large outbreaks of bird flu on poultry farms, and its recent jump to cows, there’s been surprisingly little testing of farmers and farmworkers in the U.S., and some cases have gone undetected.

Fewer than 500 people have been tested nationwide since March 2024. That’s led to criticism from advocates for farmworkers and others concerned about the potential for bird flu to trigger the next pandemic.

But targeted testing of people working with sick animals is not the only way the CDC is looking for human cases of H5 avian flu.

Public health laboratories across the country process tens of thousands of seasonal flu tests every year. And they run genomic sequencing on a large sample of those flu tests, in an effort to stay ahead of the virus’s evolutionary leaps.

It’s that routine surveillance that detected two additional human cases of bird flu this year, the cases with no known link to animals.

Those cases are a man in Missouri and a child in California, infected with a strain the CDC concluded is very similar to the one circulating in dairy cattle.

Sutton says that while we don’t know how those two individuals contracted the virus, there’s no evidence at this time that suggests those cases involved person-to-person transmission. One theory, she said, is that they were exposed to infectious wild bird droppings without realizing it.

5. For now, the recommendations are clear: Don’t drink raw milk, and avoid contact with sick or dead birds and their droppings

Testing to date has confirmed that pasteurization kills the H5N1 bird flu virus in cow milk. Milk sold to consumers under the USDA “Grade A” label is pasteurized, traceable back to the farm it came from, tightly regulated, and safe, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Sutton says public health experts don’t know for sure if drinking raw milk could lead to an infection in a human.

“We think it’s biologically plausible, and therefore we recommend against it,” she said.

Here’s why: the virus appears to be specifically infecting cows’ mammary tissue, and is present at high loads in the milk of infected cows.

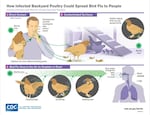

A chart from the CDC on how backyard chickens could spread avian flu. The CDC recommends people handling sick birds or cleaning out a coop after an outbreak don full PPE: goggles, respirator, gloves, disposable coveralls, and boots.

Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Unlike birds, Messer said, which tend to keel over and die, infectious cows may not all have obvious symptoms, making it harder to know for sure if raw milk is safe.

“You may be milking a cow with a runny nose and it, in fact, is dumping this virus into your milk,” he said.

Then, there’s the cats. Veterinarians believe the farm cats that died in Texas were infected with the avian flu after drinking raw milk.

Both Messer and Sutton said that even if someone is comfortable with the other known risks of raw milk, the added risk of bird flu is reason to stop drinking it.

If you’re looking at your beloved chickens and wondering if they’re worth the risk, Sutton says there’s no current guidelines suggesting you need to get rid of them.

The CDC recommends people handling sick birds or cleaning out a coop after an outbreak don full PPE: goggles, respirator, gloves, disposable coveralls, and boots.

That’s what Sutton did when her chicken died unexpectedly in 2022.

“I took that very seriously,” she said.

Best practices are to shower after handling sick birds, and monitor yourself for symptoms for 10 days.