On Friday, President Biden issued a formal apology for the federal government’s decades-long policy of placing Native American children in boarding schools as part of forced assimilation.

The apology is a first. No other sitting U.S. president has publicly apologized for the federal boarding school policies that began as early as 1819 and lasted until at least the 1960s.

“After 150 years, the United States government eventually stopped the program, but the federal government has never — never — formally apologized for what happened until today,” Biden said Friday to the cheers of a crowd assembled at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona.

“I formally apologize, as President of the United States of America, for what we did. I formally apologize and it’s long overdue.”

In this image, circa 1900s, students in uniforms pose in front of the Chemawa Indian Training School.

Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society

Throughout the boarding school era, the federal government took tens of thousands of Indigenous children from their homes and communities, forcing them into institutionalized residential schools usually operated by churches or government employees.

Children, sometimes as young as toddlers, endured rigid lives of strict discipline and harsh punishments as schools tried to erase students' Native American culture and identity.

Administrators cut the children’s long hair short, replaced their traditional clothes with uniforms and forbade them from speaking their native languages.

Gabriann Hall gives a presentation on her work in Klamath Tribes history and culture at the Tower Theater in Bend, Oregon, on March 20, 2023.

Courtesy Jeff Kastner

Klamath Tribes member Gabriann “Abby” Hall has been researching the impact of boarding schools on her own family and tribe.

She says the apology is long overdue, “Why wait so long to apologize? It’s not like the government wasn’t fully aware of what had happened, their role in it and covering it up.”

However, she adds, “I do feel that an apology is an acknowledgement and that’s the first step towards reckoning and healing.”

Indian Boarding School Initiative

In 2021, the first Native American secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, a comprehensive effort to investigate and report on the legacy of the federal Indian boarding school policies.

This summer, the department released the second volume of its report. The study identified nearly 500 federal Indian boarding schools which operated across 37 states.

“— Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs, Bryan Newland (Ojibwe)This report further proves what Indigenous peoples across the country have known for generations – that federal policies were set out to break us, obtain our territories, and destroy our cultures and our lifeways.”

The report officially identified 10 federal Indian boarding schools in Oregon. Hall says there are many more schools unaccounted for.

Hidden boarding schools

Along with the official federal boarding schools identified, the report also states over 1,000 other institutions advanced Native American assimilation and the government’s education policies.

In Oregon, documents show that government officials sent Klamath Tribes students to reform schools, the state mental hospital, the so-called Feeble Minded School, the state penitentiary and church schools.

This image, circa 1940, shows Marilyn Mitchell's application for Canyonville Bible Academy.

Courtesy of Gabriann Hall

Hall discovered that her grandmother, Marilyn Mitchell, attended boarding school at Canyonville Bible Academy, along with other Klamath Tribes members. The Academy is one of many facilities that does not appear on an official list of Native American boarding schools.

Hall also discovered other religious schools through photographs and oral history, but very few official records.

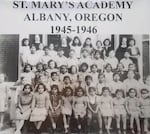

Hall says, “Just in our research, we found six schools in Oregon, Saint Mary’s (Albany) being one of them, where we know multiple Klamath tribal members went.”

‘It was hell.’

Klamath Tribes member Yvonne Parazoo began attending St. Mary’s Academy in Albany in the 1940s, along with 16 other Klamath Tribes members. She says she had just turned five years old. “The nuns were nice for the first four or five days and then it was holy hell.”

Another Klamath Tribes member who attended the school at the same time tells a similar story. Clayton Dumont Sr. remembers, “Sister Veronica, she was a hitter.”

This image, circa 1945, shows boarding school students at the St. Mary's Academy in Albany, Oregon.

Courtesy of Gabriann Hall

Oral histories like these are rare.

Hall says, “The number one thing I’ve heard in my own family and other people’s families is: They don’t talk about it.”

Records show that Klamath children attended religious schools in Klamath Falls, Mt. Angel, Beaverton and Medford, among others.

Unlike federally run boarding schools, religious school records are generally considered private, and tracking them down can be challenging.

Hall asks, “If we’re telling an accurate history in holding people accountable, why aren’t we talking about those schools?”

Digging for answers

Hall began studying Indian boarding schools when she volunteered to work on part of the curriculum for Senate Bill 13, “Tribal History/Shared History.”

The bill directed the Oregon Department of Education to develop lesson plans addressing the Native American experience in the state and make them available to school districts.

Hall says, “I was going to help write a lesson plan on Klamath tribal boarding school experiences and what I found was a complete void of records. No single list exists.”

Instead, she discovered unorganized documents scattered in libraries, archives and museums all over the country. Some are online. Most are not.

Now, some Klamath Tribes members and volunteers are trying to create a list, piecing together the names and histories of tribal members who attended boarding schools. The list currently contains over 500 names.

Most troubling to Hall is the names that disappear from records.

Hall has found that several of her ancestors died while at boarding school or soon after returning home.

Mabel Hood: Sent home to die

On May 10, 1906, Hall’s distant relative, 10-year-old Mabel Hood, exited a train at the Portland rail station and sat alone in the waiting room of the Union Depot for hours. She refused food from railway workers and would not speak except to give her name.

This image from 1905, shows Carlisle Indian Industrial student Mabel Hood.

Courtesy of Gabriann Hall

Five days earlier, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania discharged the little girl for “ill health.” Presumably, someone from the school put her on the train for Portland. It’s unknown if anyone tried to notify her parents in Klamath County.

That evening, the front page of the Oregon Journal included a story on Mabel. The headline read “Indian Girl in Plight.” According to the next day’s news report, her father happened to be in the area on business, saw the article and rushed to the train station to retrieve her.

Hall says, “We know that she was sent home with tuberculosis. What we don’t know is what happened to Mabel upon her return. We assumed that she passed away either on the way home or when she got home.”

There appear to be no further records on Mabel.

Deaths underestimated

The federal government’s recent report states that close to 1,000 children died while attending the nearly 500 identified Indian boarding schools.

The actual number of deaths is likely much higher.

Hall’s work into her genealogy shows that just two of the schools her family attended would make up nearly half that number.

Mabel, along with her sisters Rose and Tena, were among the 10,000 Native American children sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania between 1879 and 1918. Today, the former school grounds still hold the remains of nearly 200 children who died during its operation. The number of children sent home deathly ill is unknown.

In Oregon, researchers believe that between 1880 and 1945 at least 270 students died while at Chemawa Indian School in Salem. Chemawa remains the country’s longest continually operating school of its kind in the country. At least 175 students remain buried in the school’s cemetery.

As Hall says, “This history matters. It’s no longer being ignored.”

But she said on Thursday that she would be listening to the president’s apology. “I really hope that there’s some action in addition to words.”

Behind the Scenes

This article is part of an ongoing special report into Native American boarding schools, following the journey of Abby Hall as she digs into her family’s history.

The one-hour “Oregon Experience” documentary, Uncovering Boarding Schools: stories of resistance and resilience, is expected to be completed in the spring of 2025.

In this image from May 2024, cinematographer LaRonn Katchia films as Abby Hall speaks with a Klamath Tribes elder at the Klamath Tribes offices in Chiloquin, Oregon.

Courtesy of Kami Horton

The “Oregon Experience” team has spent the last several months with Abby, researching into her family’s history, talking to elders and trying to uncover the often disturbing stories of several generations of children sent away to grow up in boarding schools. Some never returned.